Shocking video of The Ocean Race crash

Published on June 15th, 2023 by Editor -->

In a shocking incident during the start of Leg 7 of The Ocean Race , a major collision between 11th Hour Racing Team and GUYOT environnement – Team Europe saw both boats return to the dock with serious damage.

Race details – Route – Tracker – Scoreboard – Content from the boats – YouTube

IMOCA Overall Leaderboard (after 6 of 7 legs) 1. 11th Hour Racing Team — 33 points 2. Team Holcim-PRB — 31 points 3. Team Malizia — 27 points 4. Biotherm — 19 points 5. GUYOT environnement – Team Europe — 2 points

VO65 Overall Leaderboard (after 2 of 3 legs): 1. WindWhisper Racing Team — 12 points 2. Team JAJO — 9 points 3. Austrian Ocean Racing powered by Team Genova — 7 points 4. Mirpuri/Trifork Racing Team — 5 points 5. Viva México — 4 points 6. Ambersail 2 — 3 points

IMOCA: Name, Design, Skipper, Launch date • Guyot Environnement – Team Europe (VPLP Verdier); Benjamin Dutreux (FRA)/Robert Stanjek (GER); September 1, 2015 • 11th Hour Racing Team (Guillaume Verdier); Charlie Enright (USA); August 24, 2021 • Holcim-PRB (Guillaume Verdier); Kevin Escoffier (FRA); May 8, 2022 • Team Malizia (VPLP); Boris Herrmann (GER); July 19, 2022 • Biotherm (Guillaume Verdier); Paul Meilhat (FRA); August 31 2022

The Ocean Race 2022-23 Race Schedule: Alicante, Spain – Leg 1 (1900 nm) start: January 15, 2023 Cabo Verde – ETA: January 22; Leg 2 (4600 nm) start: January 25 Cape Town, South Africa – ETA: February 9; Leg 3 (12750 nm) start: February 26 Itajaí, Brazil – ETA: April 1; Leg 4 (5500 nm) start: April 23 Newport, RI, USA – ETA: May 10; Leg 5 (3500 nm) start: May 21 Aarhus, Denmark – ETA: May 30; Leg 6 (800 nm) start: June 8 Kiel, Germany (Fly-By) – June 9 The Hague, The Netherlands – ETA: June 11; Leg 7 (2200 nm) start: June 15 Genova, Italy – The Grand Finale – ETA: June 25, 2023; Final In-Port Race: July 1, 2023

The Ocean Race (formerly Volvo Ocean Race and Whitbread Round the World Race) was initially to be raced in two classes of boats: the high-performance, foiling, IMOCA 60 class and the one-design VO65 class which has been used for the last two editions of the race.

However, only the IMOCAs will be racing round the world while the VO65s will race in The Ocean Race VO65 Sprint which competes in Legs 1, 6, and 7 of The Ocean Race course.

Additionally, The Ocean Race also features the In-Port Series with races at seven of the course’s stopover cities around the world which allow local fans to get up close and personal to the teams as they battle it out around a short inshore course.

Although in-port races do not count towards a team’s overall points score, they do play an important part in the overall rankings as the In-Port Race Series standings are used to break any points ties that occur during the race around the world.

Held every three or four years since 1973, the 14th edition of The Ocean Race was originally planned for 2021-22 but was postponed one year due to the pandemic, with the first leg starting on January 15, 2023.

Tags: 11th Hour Racing Team , The Ocean Race , TOR23-Leg 7

Related Posts

Pirates in the Indian Ocean →

The Ocean Race Europe begins in Kiel →

Challenges, triumphs, and team spirit →

To become a sustainable sports team →

© 2024 Scuttlebutt Sailing News. Inbox Communications, Inc. All Rights Reserved. made by VSSL Agency .

- Privacy Statement

- Advertise With Us

Get Your Sailing News Fix!

Your download by email.

- Your Name...

- Your Email... *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- CLASSIFIEDS

- NEWSLETTERS

- SUBMIT NEWS

SailGP Bermuda: Dramatic onboard video of the collision between USA and Japan in SailGP Bermuda

Related Articles

- Rugby union

US and Japanese sailing boats collide during Bermuda Grand Prix – video

In the first race of the Bermuda Grand Prix, the US and Japanese teams collided and became entangled. The crash ruled both boats out of the rest of the day's racing and also led to the US boat capsize shortly afterwards. It was the first event for Jimmy Spithill, helmsman and America's Cup winner, as part of the US SailGP team.

Source: APTN

Mon 26 Apr 2021 11.41 BST Last modified on Mon 26 Apr 2021 13.27 BST

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share via Email

Most popular

- The Ocean Race

- Calendar - Results

- Football Home

- Fixtures - Results

- Premier League

- Champions League

- Europa League

- All Competitions

- All leagues

- Snooker Home

- World Championship

- UK Championship

- Major events

- Olympics Home

- Tennis Home

- Australian Open

- Roland-Garros

- Mountain Bike Home

- UCI Track CL Home

- Men's standings

- Women's standings

- Cycling Home

- Race calendar

- Tour de France

- Vuelta a España

- Giro d'Italia

- Dare to Dream

- Alpine Skiing Home

- Athletics Home

- Diamond League

- World Championships

- World Athletics Indoor Championships

- Biathlon Home

- Cross-Country Skiing Home

- Cycling - Track

- Equestrian Home

- Figure Skating Home

- Formula E Home

- Calendar - results

- DP World Tour

- MotoGP Home

- Motorsports Home

- Speedway GP

- Clips and Highlights

- Rugby World Cup predictor

- Premiership

- Champions Cup

- Challenge Cup

- All Leagues

- Ski Jumping Home

- Speedway GP Home

- Superbikes Home

- The Ocean Race Home

- Triathlon Home

- Hours of Le Mans

- Winter Sports Home

'Absolutely incredible' crash leaves 11th Hour Racing Team's hopes of winning the Ocean Race 2022-23 in tatters

/dnl.eurosport.com/sd/img/placeholder/eurosport_logo_1x1.png)

Updated 16/06/2023 at 09:21 GMT

The hopes of 11th Hour Racing Team of winning The Ocean Race 2022-23 suffered a big blow as they were left with damage to their boat following a crash with GUYOT environnement - Team Europe. Both IMOCA boats headed back to shore for repairs following the incident at the start of Leg 7, which is the final leg of the race. The standings are currently led by 11th Hour Racing Team.

'Absolutely incredible' - 11th Hour Racing Team suffer serious damage after crash

Kiel confirmed as starting point for The 2025 Ocean Race Europe

14/02/2024 at 14:10

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2023/06/16/3727872-75847368-2560-1440.png)

'Typically they would give a compensation' - Race chairman Brisius explains jury protocol

- Team JAJO lead VO65 Sprint

- Clapcich left 'hanging' to the boat in dramatic moment

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2023/06/15/3727694-75843813-2560-1440.jpg)

‘Situation is so unique’ - Enright vows to fight on after 11th Hour Racing Team crash

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2023/06/15/3727700-75843933-2560-1440.jpg)

Highlights from start of Leg 7 of The Ocean Race 2022-23 as 11th Hour Racing and GUYOT crash

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2023/06/15/3727698-75843893-2560-1440.jpg)

‘It is our fault’ - Dutreux sorry for crash with 11th Hour Racing Team

‘A massive survival element’ - Lush on The Ocean Race ahead of new documentary

02/11/2023 at 09:44

New Warner Bros. Discovery documentary goes behind-the-scenes of sailing's toughest team test

02/11/2023 at 09:40

A Voyage of Discovery: The Ocean Race - Coming Soon!

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- March Madness

- AP Top 25 Poll

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Survivors of Calif sailboat race accident released

- Copy Link copied

LOS ANGELES (AP) — Five sailors who survived when their boat smashed into rocks during a race in storm-churned seas off Southern California, killing a fellow crewmember, have been released from San Diego hospitals.

The survivors were treated for cuts, bruises and hypothermia, Chuck Hope, commodore of the San Diego Yacht Club, told UT San Diego Sunday (http://bit.ly/14KsMEg). The yacht club was a co-host of the 139-nautical-mile Islands Race.

The five crewmembers of the Uncontrollable Urge were rescued after the 32-foot sailboat lost its steering and the craft began drifting toward San Clemente Island, where it broke apart, Coast Guard Petty Officer Connie Gawrelli said Saturday.

Craig Thomas Williams, a 36-year-old architect from Serra Mesa, was killed. Race officials identified the other crew members as James Gilmore, the skipper and owner of the boat; Mike Skillicorn; Doug Pajak; Ryan Georgianna; and Vince Valdes.

On Friday night, the crew radioed the mayday call and also activated a feature on the boat that provides authorities with GPS coordinates and other crucial information, she said. But the crew then declined assistance and instead requested a tow boat. Stormy conditions, however, kept the tow boat from getting to them.

“They were not in immediate danger and thought they would be able to manage completing the race and get assistance on their own,” Hope said. “Then things got worse.”

He said the crew couldn’t deploy a life raft or anchor the boat. They abandoned ship when the boat entered the surf line and broke apart.

When the Coast Guard reached the crew, they found Williams unresponsive in the water, the San Diego County Medical Examiner’s office said. He and the other five crew members were hoisted into a helicopter and flown to a hospital.

Williams was a member of the Silver Gate Yacht Club in San Diego, where the Uncontrollable Urge is docked, said Carey Storm, the club’s commodore.

“This is a very difficult time for the Williams family, the skipper of Uncontrollable Urge and the other surviving crew members,” Carey Storm said. "(The club) and the entire Southern California racing community is a close family, and the loss of one of our members impacts us all greatly.”

Carey said Sunday that a memorial fund has been established to help support Williams’ young daughter and wife, who is pregnant.

Gilmore, the owner of the Uncontrollable Urge, tweeted Friday that he was taking the new boat on its first race, and noted that the forecast called for 25-knot winds.

“Gonna see what this boat can do!” he tweeted.

Hope said the Uncontrollable Urge was known within the sailboat racing circuit and that its crew and skipper were experienced.

“Those guys been around, they’re very good sailors,” he said. “This was not a case of someone getting in over their head.”

He said stormy conditions in the open seas caused equipment failures for two other boats, forcing their crews to drop from the race. The Uncontrollable Urge crew radioed that the boat’s rudder failed.

“This was not an isolated incident,” Hope said. “Conditions were pretty fierce.”

The overnight race began in Newport Harbor in Orange County on Friday and was to take participants around Catalina and San Clemente islands before finishing off in San Diego’s Point Loma.

Man Killed as Waves, Rocks Ripped Apart Sailboat in Race

"uncontrollable urge” is a columbia carbon 32 owned by james gilmore of the silver gate yacht club on shelter island., by r. stickney and monica garske • published march 9, 2013 • updated on march 10, 2013 at 4:25 pm.

San Diego-based U.S. Coast Guard crews launched a rescue mission for a sailboat broken apart by waves in an 8-foot surf off San Clemente Island late Friday.

One person died and five others were rescued from the surf in hazardous weather conditions caused by a powerful winter storm.

The 30-foot sailboat was competing in the Islands Race when the vessel’s rudder failed around 9:30 p.m.

The crew tried to launch but couldn’t because of weather conditions. A 10-knot wind and a small craft advisory were in effect at the time, according to the U.S. Coast Guard.

As the “Uncontrollable Urge” crew tried to anchor, they drifted closer to the island located southwest of Catalina off the coast of Southern California.

That’s when an MH-60 Jayhawk helicopter crew launched from Coast Guard Sector San Diego and Coast Guard Cutter Edisto.

The sailboat eventually broke apart at the rocky surf line, according to the USCG, and six people were pulled from the water.

Crew members were taken to UCSD and Mercy Hospitals for treatment.

The sailors initiated a mayday call at 9:30 p.m. but refused help from nearby boaters or the Coast Guard. The rescue mission was launched more than an hour later when the crew decided to abandon the vessel.

The “Uncontrollable Urge” is a Columbia Carbon 32 owned by James Gilmore of the Silver Gate Yacht Club on Shelter Island.

Share your feedback with NBC 7 San Diego

Carlsbad woman celebrates her 104th birthday

The day before the race Gilmore posted updates on Twitter about taking out the "new Urge" for a race.

"Gonna see what this boat can do!" he tweeted.

The Islands Race, sponsored by the Newport Harbor Yacht Club and San Diego Yacht Club, involves a course that runs 139 nautical miles rounding Catalina and San Clemente Islands. A map that live-tracked the race can be seen here.

On Saturday morning the Silver Gate Yacht Club of Shelter Island released the following statement about the fatal sailboat accident: “Silver Gate Yacht Club is very sad to acknowledge the loss of one of our members, as well as the loss of a member's boat. This is a tragedy for the families and our club is in mourning for the loss of life. We will be respecting the privacy of the family by not releasing any further information until a time of the family's choosing.”

A report released by the county medical examiner’s office Saturday afternoon confirmed that 36-year-old San Diego resident Craig Williams was the victim killed in the sailboat accident. When Coast Guard crews reached the boat, they discovered Williams unresponsive in the water, the report confirms. He was pulled from the water and pronounced dead at the scene.

According to the San Diego Yacht Club website, Williams owned his own boat named "Uproarious."

Friends and fellow sailors say Williams was an avid sailor and devoted husband and father. He leaves behind a 2-year-old daughter and wife, who is expecting the couple's second child.

A memorial fund has been established for Williams' family. To donate, click here.

Racing the Storm: The Story of the Mobile Bay Sailing Disaster

When hurricane-force winds suddenly struck the Bay, they swept more than 100 boaters into one of the worst sailing disasters in modern American history

Matthew Teague, Photographs by Brian Schutmaat, Illustrations by Michael Byers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/d7/8fd7f047-a084-4e32-a01b-a9ceec77b452/julaug2017_a07_disasteratsea.jpg)

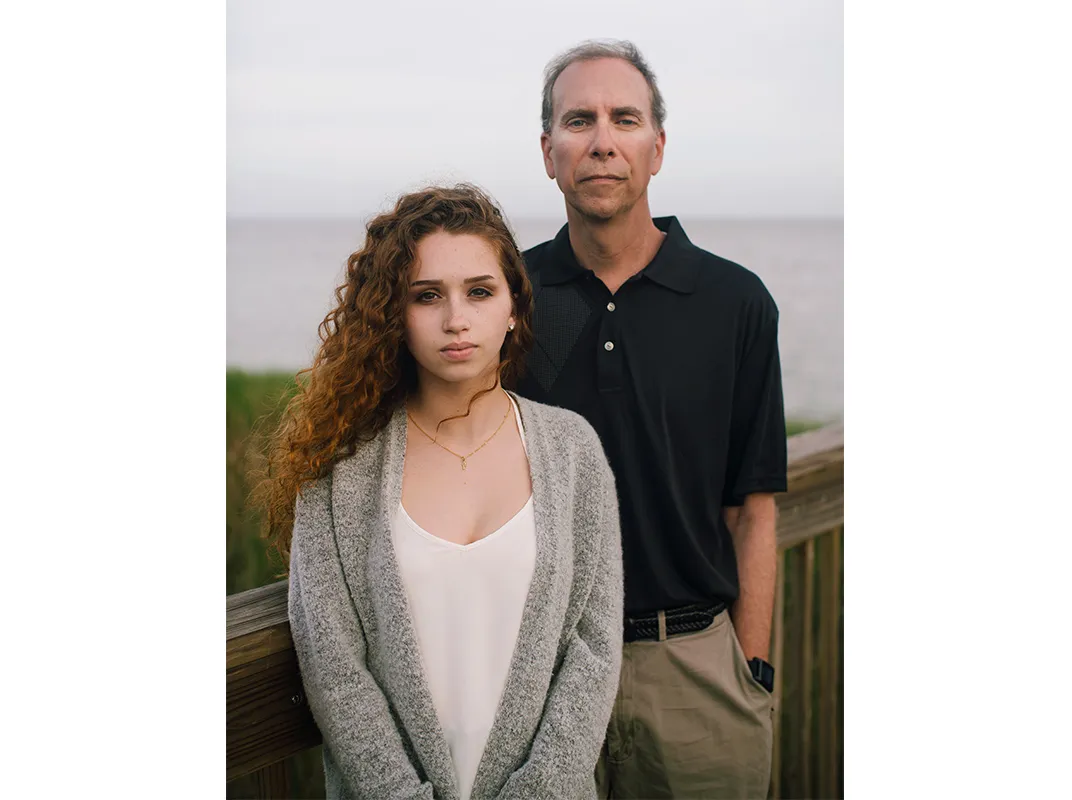

The morning of April 25, 2015, arrived with only a whisper of wind. Sailboats traced gentle circles on Alabama’s Mobile Bay, preparing for a race south to the coast.

On board the Kyla , a lightweight 16-foot catamaran, Ron Gaston and Hana Blalack practiced trapezing. He tethered his hip harness to the boat, then leaned back over the water as the boat tilted and the hull under their feet went airborne.

“Physics,” he said, grinning.

They made an unusual crew. He was tall and lanky, 50 years old, with thinning hair and decades of sailing experience. She was 15, tiny and pale and redheaded, and had never stepped on a sailboat. But Hana trusted Ron, who was like a father to her. And Ron’s daughter, Sarah, was like a sister.The Dauphin Island Regatta first took place more than half a century ago and hasn’t changed much since. One day each spring, sailors gather in central Mobile Bay and sprint 18 nautical miles south to the island, near the mouth of the bay in the Gulf of Mexico. There were other boats like Ron’s, Hobie Cats that could be pulled by hand onto a beach. There were also sleek, purpose-built race boats with oversized masts—the nautical equivalent of turbocharged engines—and great oceangoing vessels with plush cabins belowdecks. Their captains were just as varied in skill and experience.

A ripple of discontent moved through the crews as the boats circled, waiting. The day before, the National Weather Service had issued a warning: “A few strong to severe storms possible on Saturday. Main Threat: Damaging wind.”

Now, at 7:44 a.m., as sailors began to gather on the bay for a 9:30 start, the yacht club’s website posted a message about the race in red script:

“Canceled due to inclement weather.” A few minutes later, at 7:57 a.m., the NWS in Mobile sent out a message on Twitter:

Don't let your guard down today - more storms possible across the area later this afternoon! #mobwx #alwx #mswx #flwx — NWS Mobile (@NWSMobile) April 25, 2015

But at 8:10 a.m., strangely, the yacht club removed the cancellation notice, and insisted the regatta was on.

All told, 125 boats with 475 sailors and guests had signed up for the regatta, with such a variety of vessels that they were divided into several categories. The designations are meant to cancel out advantages based on size and design, with faster boats handicapped by owing race time to slower ones. The master list of boats and their handicapped rankings is called the “scratch sheet.”

Gary Garner, then commodore of the Fairhope Yacht Club, which was hosting the regatta that year, said the cancellation was an error, the result of a garbled message. When an official on the water called into the club’s office and said, “Post the scratch sheet,” Garner said in an interview with Smithsonian , the person who took the call heard, “Scratch the race” and posted the cancellation notice. Immediately the Fairhope Yacht Club received calls from other clubs around the bay: “Is the race canceled?”

“‘No, no, no, no,’” Garner said the Fairhope organizers answered. “‘The race is not canceled.’”

The confusion delayed the start by an hour.

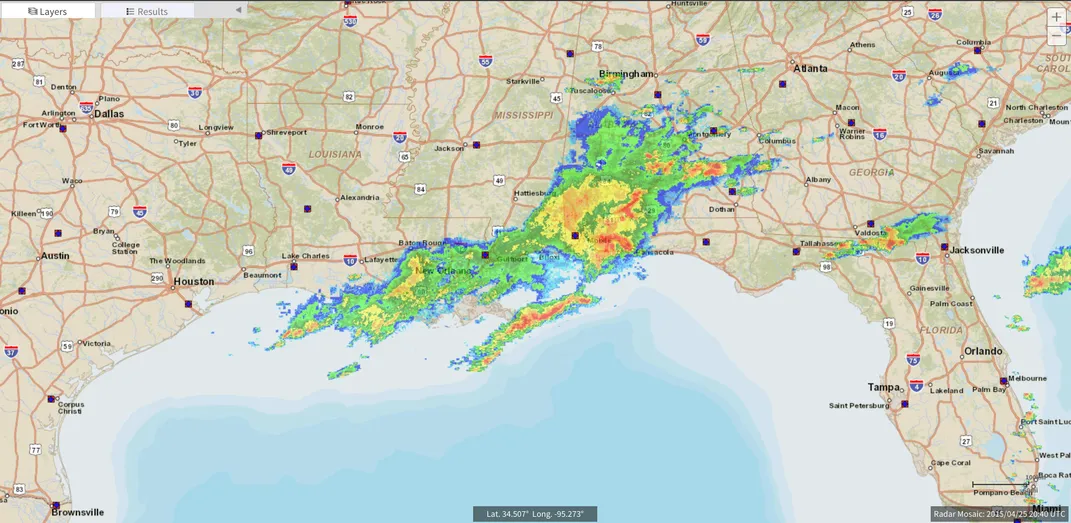

A false start cost another half-hour, and the boats were still circling at 10:45 a.m. when the NWS issued a more dire prediction for Mobile Bay: “Thunderstorms will move in from the west this afternoon and across the marine area. Some of the thunderstorms may be strong or severe with gusty winds and large hail the primary threat.”

Garner said later, “We all knew it was a storm. It’s no big deal for us to see a weather report that says scattered thunderstorms, or even scattered severe thunderstorms. If you want to go race sailboats, and race long-distance, you’re going to get into storms.”

The biggest, most expensive boats had glass cockpits stocked with onboard technology that promised a glimpse into the meteorological future, and some made use of specialized fee-based services like Commanders’ Weather, which provides custom, pinpoint forecasts; even the smallest boats carried smartphones. Out on the water, participants clustered around their various screens and devices, calculating and plotting. People on the Gulf Coast live with hurricanes, and know to look for the telltale rotation on weather radar. April is not hurricane season, of course, and this storm, with deceptive straight-line winds, didn’t take that shape.

Only eight boats withdrew.

On board the Razr , a 24-foot boat, 17-year-old Lennard Luiten, his father and three friends scrutinized incoming weather reports in granular detail: The storm appeared likely to arrive at 4:15 p.m., they decided, which should give them time to run down to Dauphin Island, cross the finish line, spin around, and return to home port before the front arrived.

Just before a regatta starts, a designated boat carrying race officials deploys flag signals and horn blasts to count down the minutes. Sailors test the wind and jockey for position, trying to time their arrival at the starting line to the final signal, so they can carry on at speed.

Lennard felt thrilled as the moment approached. He and his father, Robert, had bought the Razr as a half-sunk lost cause, and spent a year rebuilding it. Now the five crew members smiled at each other. For the first time, they agreed, they had the boat “tuned” just right. They timed their start with precision—no hesitation at the line—then led the field for the first half-hour.

The small catamarans were among the fastest boats, though, and the Kyla hurtled Hana and Ron forward. On the open water Hana felt herself relax. “Everything slowed down,” she said. She and Ron passed a 36-foot monohull sailboat called the Wind Nuts , captained by Ron’s lifelong friend Scott Godbold. “Hey!” Ron called out, waving.

Godbold, a market specialist with an Alabama utility company whose grandfather taught him to sail in 1972, wasn’t racing, but he and his wife, Hope, had come to watch their son Matthew race and to help out if anyone had trouble. He waved back.

Not so long ago, before weather radar and satellite navigation receivers and onboard computers and racing apps, sailors had little choice but to be cautious. As James Delgado, a maritime historian and former scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, puts it, they gave nature a wider berth. While new information technology generally enhances safety, it can, paradoxically, bring problems of its own, especially when its dazzling precision encourages boaters to think they can evade danger with minutes to spare. Today, Delgado says, “sometimes we tickle the dragon’s tail.” And the dragon may be stirring, since many scientists warn that climate change is likely to increase the number of extraordinary storms.

Within a few hours of the start of the 2015 Dauphin Island Regatta, as boats were still streaking for the finish line, the storm front reached the port of Pascagoula, Mississippi, 40 miles southwest of Mobile. It slammed into the side of the Manama , a 600-foot oil tanker weighing almost 57,000 tons, and heaved it aground.

Mobile Bay, about 30 miles long and half as wide, is fed from the north by five rivers, so that depending on the tide and inland rains, the bay smells some days of sea salt, and others of river silt. A deep shipping channel runs up its center, but much of the bay is so shallow an adult could stand on its muddy bottom. On the northwestern shore stands the city of Mobile, dotted with shining high-rises. South of the city is a working waterfront—shipyards, docks. Across the bay, on the eastern side, a high bluff features a string of picturesque towns: Daphne, Fairhope, Point Clear. To the south, the mouth of the bay is guarded by Dauphin Island and Fort Morgan peninsula. Between them a gap of just three miles of open water leads into the vast Gulf of Mexico.

During the first half of the race, Hana and Ron chased his brother, Shane Gaston, who sailed on an identical catamaran. Halfway through the race he made a bold move. Instead of sailing straight toward Dauphin Island—the shortest route—he tacked due west to the shore, where the water was smoother and better protected, and then turned south.

It worked. “We’re smoking!” he told Hana.

Conditions were ideal at that point, about noon, with high winds but smooth water. About 2 p.m., as they arrived at the finish line, the teenager looked back and laughed. Ron’s brother was a minute behind them.

“Hey, we won!” she said.

Typically, once crews finish the race they pull into harbor at Dauphin Island for a trophy ceremony and a night’s rest. But the Gaston brothers decided to turn around and sail back home, assuming they’d beat the storm; others made the same choice. The brothers headed north along the bay’s western shore. During the race Ron had used an out-of-service iPhone to track their location on a map. He slipped it into a pocket and sat back on the “trampoline”—the fabric deck between the two hulls.

Shortly before 3 p.m., he and Hana watched as storm clouds rolled toward them from the west. A heavy downpour blurred the western horizon, as though someone had smudged it with an eraser. “We may get some rain,” Ron said, with characteristic understatement. But they seemed to be making good time—maybe they could make it to the Buccaneer Yacht Club, he thought, before the rain hit.

Hana glanced again and again at a hand-held GPS and was amazed at the speeds they were clocking. “Thirteen knots!” she told Ron. Eventually she looped its cord around her neck so she could keep an eye on it, then tucked the GPS into her life preserver so she wouldn’t lose it.

By now the storm, which had first come alive in Texas, had crossed three states to reach the western edge of Mobile Bay. Along the way it developed three separate storm cells, like a three-headed Hydra, each dense with cold air and icy particulates held aloft by a warm updraft, like a hand cradling a water balloon. Typically a cold mass will simply dissipate, but sometimes as a storm moves across a landscape something interrupts the supporting updraft. The hand flinches, and the water balloon falls: a downburst, pouring cold air to the surface. “That by itself is not an uncommon phenomenon,” says Mark Thornton, a meteorologist and member of U.S. Sailing, a national organization that oversees races. “It’s not a tragedy, yet.”

During the regatta, an unknown phenomenon—a sudden shift in temperature or humidity, or the change in topography from trees, hills and buildings to a frictionless expanse of open water—caused all three storm cells to burst forth at the same moment, as they reached Mobile Bay. “And right on top of hundreds of people,” Thornton said. “That’s what pushes it to historic proportions.”

At the National Weather Service’s office in Mobile, meteorologists watched the storm advance on radar. “It really intensified as it hit the bay,” recalled Jason Beaman, the meteorologist in charge of coordinating the office’s warnings. Beaman noted the unusual way the storm, rather than blow itself out quickly, kept gaining in strength. “It was an engine, like a machine that keeps running,” he said. “It was feeding itself.”

Storms of this strength and volatility epitomize the dangers posed by a climate that may be increasingly characterized by extreme weather. Thornton said that it wouldn’t be “scientifically appropriate” to attribute any storm to climate change, but said “there is a growing consensus that climate change is increasing the frequency of severe storms.” Beaman suggests more research should be devoted to better understanding what’s driving individual storms. “The technology we have just isn’t advanced enough right now to give us the answer,” he said.

On Mobile Bay, the downbursts sent an invisible wave of air rolling ahead of the storm front. This strange new wind pushed Ron and Hana faster than they had gone during any point in the race.

“They’re really getting whipped around,” he told a friend. “This is how they looked during Katrina.”

A few minutes later the MRD’s director called from Dauphin Island. “Scott, you’d better get some guys together,” he said. “This is going to be bad. There are boats blowing up onto the docks here. And there are boats out on the bay.”

The MRD maintains a camera on the Dauphin Island Bridge, a three-mile span that links the island to the mainland. At about 3 p.m., the camera showed the storm’s approach: whitecaps foaming as wind came over the bay, and beyond that rain at the far side of the bridge. Forty-five seconds later, the view went completely white.

Under the bridge, 17-year-old Sarah Gaston—Ron’s daughter, and Hana’s best friend—struggled to control a small boat with her sailing partner, Jim Gates, a 74-year-old family friend.

“We just were looking for any land at that point,” Sarah said later. “But everything was white. We couldn’t see land. We couldn’t even see the bridge.”

The pair watched the jib, a small sail at the front of the boat, ripping in slow motion, as if the hands of some invisible force tore it from left to right.

Farther north, the Gaston brothers on their catamarans were getting closer to the Buccaneer Yacht Club, on the bay’s western shore.

Lightning crackled. “Don’t touch anything metal,” Ron told Hana. They huddled on the center of their boat’s trampoline.

Sailors along the edges of the bay had reached a decisive moment. “This is the time to just pull in to shore,” Thornton said. “Anywhere. Any shore, any gap where you could climb on to land.”

Ron tried. He scanned the shore for a place where his catamaran could pull in, if needed. “Bulkhead...bulkhead...pier...bulkhead,” he thought. The walled-off western side of the bay offered no harbor. Less than two miles behind, his brother Shane, along with Shane’s son Connor, disappeared behind a curtain of rain.

“Maybe we can outrun it,” Ron told Hana.

But the storm was charging toward them at 60 knots. The world’s fastest boats—giant carbon fiber experiments that race in the America’s Cup, flying on foils above the water, requiring their crew to wear helmets—couldn’t outrun this storm.

Lightning flickered in every direction now, and within moments the rain caught up. It came so fast, and so dense, that the world seemed reduced to a small gray room, with no horizon, no sky, no shore, no sea. There was only their boat, and the needle-pricks of rain.

The temperature tumbled, as the downbursts cascaded through the atmosphere. Hana noticed the sudden cold, her legs shaking in the wind.

Then, without warning, the gale dropped to nothing. No wind. Ron said, “What in the wor”—but a spontaneous roar drowned out his voice. The boat shuddered and shook. Then a wall of air hit with a force unlike anything Ron had encountered in a lifetime of sailing.

The winds rose to 73 miles per hour—hurricane strength—and came across the bay in a straight line, like an invisible tsunami. Ron and Hana never had a moment to let down their sails.

The front of the Kyla rose up from the water, so that it stood for an instant on its tail, then flipped sideways. The bay was only seven feet deep at that spot, so the mast jabbed into the mud and snapped in two.

Hana flew off, hitting her head on the boom, a horizontal spar attached to the mast. Ron landed between her and the boat, and grabbed her with one hand and a rope attached to the boat with the other.

The boat now lay in the water on its side, and the trampoline—the boat’s fabric deck—stood vertical, and caught the wind like a sail. As it blew away, it pulled Ron through the water, away from Hana, stretching his arms until he faced a decision that seemed surreal. In that elongated moment, he had two options: He could let go of the boat, or Hana.

He let go of the boat, and in seconds it blew away beyond the walls of their gray room. The room seemed to shrink with each moment. Hana extended an arm and realized she couldn’t see beyond her own fingers. She and Ron both still wore their life jackets, but eight-foot swells crashed on them, threatening to separate them, or drown them on the surface.

The two wrapped their arms around each other, and Hana tucked her head against Ron’s chest to find a pocket of air free from the piercing rain.

In the chaos, Ron thought, for a moment, of his daughter. But as he and Hana rolled together like a barrel under the waves, his mind went blank and gray as the seascape.

Sarah and Jim’s boat had also risen up in the wind and bucked them into the water.

The mast snapped, sending the sails loose. “Jim!” Sarah cried out, trying to shift the sails. Finally, they found each other, and dragged themselves back into the wreckage of their boat.

About 30 miles north, a Coast Guard ensign named Phillip McNamara stood his first-ever shift as duty officer. As the storm bore down on Mobile Bay, distress calls came in from all along the coast: from sailors in the water, people stranded on sandbars, frantic witnesses on land. Several times he rang his superior, Cmdr. Chris Cederholm, for advice about how to respond, each time with increasing urgency.

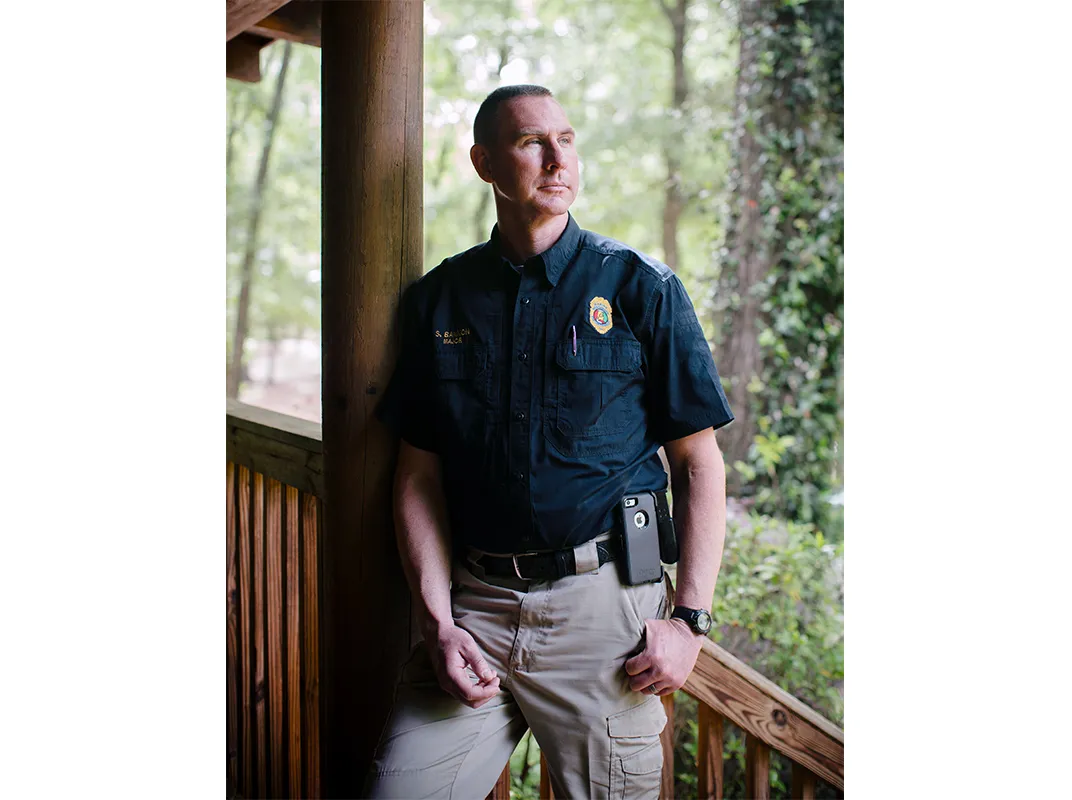

About 15 miles inland, Scott Bannon, a major with Alabama’s Marine Resources Division, looked up through the high windows in his log home west of Mobile. Bannon lives on a pine-covered hill and has seen so many hurricanes blow through that he can measure their strength by the motion of the treetops.

“By the third call it was clear something big was happening,” Cederholm said recently. When Cederholm arrived at the station, he understood the magnitude of the disaster—scores of people in the water—and he triggered a Coast Guard protocol called a “Mass Rescue Operation,” summoning a response from air, land and sea.

As authorities scrambled to grasp the scale of the storm, hundreds of sailors on the bay struggled to survive it. The wind hit the Luitens’ Razr so fast it pinned the sails to the mast; there was no way to lower them. The wind flipped the boat, slinging the crew—Lennard, his father, Robert, 71-year-old Jimmie Brown, and teenage friends Adam Clark and Jacob Pouncey—into the water. Then the boat barrel-rolled, and Lennard and Brown were briefly scooped back onto its deck before the keel snapped and they were tossed once again, this time in the other direction.

Brown struggled in a raincoat. Lennard, a strong swimmer, swam around the boat, searching for his dad, whom he found with Jacob. After 20 minutes or so, towering eight-foot waves threatened to drown them, and Lennard struck out for the shore to find help.

Normally, a storm’s hard edge blows past in two or three minutes; this storm continued for 45 minutes.

An experienced sailor named Larry Goolsby, captain of a 22-foot boat named Team 4G , was in sight of the finish line when the storm came on; he and two crew members had just moments to ease the sails before the wind hit. The gale rolled the boat over twice, before a much heavier 40-foot vessel hove into view upwind. The bigger boat was moving with all the force of the storm at its back, and bearing down on the three men.

One shouted over the wind, “They’re going to hit us!” just as the bigger boat smashed into the Team 4G , running it over and dragging the smaller boat away.

The crew members had managed to jump clear into the water just before impact. In the same instant, Goolsby grabbed a rope dangling from the charging boat and swung himself up onto its deck. Reeling, he looked back to see his crew mates in the water, growing more distant by the second. None were wearing life jackets. Goolsby snatched a life ring from the deck of the runaway vessel and dove back into the water, hoping to save his friends.

Similar crises unfolded across the bay. A 26-foot boat named the Scoundrel had finished the race and turned north when the storm hit. The wind knocked the boat on its side before the captain had time to let down the sails. As the boat lay horizontal, he leaped into the water, let loose the sails, and then scrambled back aboard as the ship righted itself. But one crew member, he saw, 27-year-old Kristopher Beall, had fallen in, and was clinging to a rope trailing the boat. The 72-year-old captain tried to haul him in as Beall gasped for air amid the waves.

A dozen Coast Guard ships from Mississippi to Florida responded, along with several airplanes, helicopters and a team of searchers who prowled the coastline on all-terrain vehicles. People on horses searched the bay’s clay banks for survivors.

At the Coast Guard outpost on Dauphin Island, Bannon, the marine resources officer, made call after call to the families and friends of boat owners and captains, trying to work out how many people might be missing. The regatta organizers kept a tally of captains, but not of others who were on board the boats.

Cederholm, the Coast Guard commander, alerted the military chain of command, all the way up to three-star admiral William Lee. “I’ve never seen anything like this,” the 34-year veteran of the sea told Cederholm.

Near the Dauphin Island Bridge, a Coast Guard rescue boat picked up Sarah Gaston and Jim Gates. She had suffered a leg injury and hypothermia, and as her rescuers pulled her onto their deck, she went into shock.

Ron and Hana were closer to the middle of the bay, where the likelihood of rescue was frighteningly low. “All you can really see above water is someone’s head,” Bannon explained later. “A human head is about the size of a coconut. So you’re on a ship that’s moving, looking for a coconut bobbing between waves. You can easily pass within a few feet and never see someone in the water.”

Ron and Hana had now been in the water for two hours. They tried to swim for shore, but the waves and current locked them in place. To stave off the horror of their predicament, Hana made jokes. “I don’t think we’re going to make it home for dinner,” she said.

“Look,” Ron said, pulling the phone from his pocket. Even though it was out of service, he could still use it to make an emergency call. At the same moment, Hana pulled the GPS unit from her life jacket and held it up.

Ron struggled with wet fingers to dial the phone. “Here,” he said, handing it to Hana. “You’re the teenager.”

She called 911. A dispatcher answered: “What is your emergency and location?”

“I’m in Mobile Bay,” Hana said.

“The bay area?”

“No, ma’am. I’m in the bay. I’m in the water.”

Using the phone and GPS, and watching the blue lights of a patrol boat, Hana guided rescuers to their location.

As an officer pulled her from the water and onto the deck, the scaffolding of Hana’s sense of humor started to collapse. She asked, “This boat isn’t going to capsize too, is it?”

Ron’s brother and nephew, Shane and Connor, had also gone overboard. Three times the wind flipped their boat on its side before it eventually broke the mast. They used the small jib sail to fight their way toward the western shore. Once on land, they knocked on someone’s door, borrowed a phone, and called the Coast Guard to report that they’d survived.

The three-man crew of the Team 4G clung to their commandeered life ring, treading water until they were rescued.

Afterward, the Coast Guard hailed several volunteer rescuers who helped that day, including Scott Godbold, who had come out with his wife, Hope, to watch their son Matthew. As the sun started to set that evening, the Godbolds sailed into the Coast Guard’s Dauphin Island station with three survivors.

“It was amazing,” said Bannon. The odds against finding even one person in more than 400 square miles of choppy sea were outrageous. Behind Godbold’s sailboat, they also pulled a small inflatable boat, which held the body of Kristopher Beall.

After leaving Hope and the survivors at the station, Godbold was joined by his father, Kenny, who is in his 70s, and together they stepped back onto their boat to continue the search. Scott had in mind a teenager he knew: Lennard Luiten, who remained missing. Lennard’s father had been found alive, as had his friend Jacob. But two other Razr crew members—Jacob’s friend, Adam, and Jimmie Brown—had not survived.

By this point Lennard would have been in the water, without a life jacket, for six hours. Night had come, and the men knew the chances of finding the boy were vanishingly remote. Scott used the motor on his boat to ease out into the bay, listening for any sound in the darkness.

Finally, a voice drifted over the water: “Help!”

Hours earlier, as the current swept Lennard toward the sea, he had called out to boat after boat: a Catalina 22 racer, another racer whom Lennard knew well, a fisherman. None had heard him. Lennard swam toward an oil platform at the mouth of the bay, but the waves worked against him, and he watched the platform move slowly from his south to his north. There was nothing but sea and darkness, and still he hoped: Maybe his hand would find a crab trap. Maybe a buoy.

Now Kenny shined a flashlight into his face, and Scott said, “Is that you, Lennard?”

Ten vessels sank or were destroyed by the storm, and 40 people were rescued from the water. A half-dozen sailors died: Robert Delaney, 72, William Massey, 67, and Robert Thomas, 50, in addition to Beall, Brown and Clark.

It was one of the worst sailing disasters in American history.

Scott Godbold doesn’t talk much about that day, but it permeates his thoughts. “It never goes away,” he said recently.

The search effort strained rescuers. Teams moved from one overturned boat to another, where they would knock on the hull and listen for survivors, before divers swam underneath to check for bodies. Cederholm, the Coast Guard commander, said that at one point he stepped into his office, shut the door and tried to stifle his emotions.

Working with the Coast Guard, which is currently investigating the disaster, regatta organizers have adopted more stringent safety measures, including keeping better records of boat crew and passenger information during races. The Coast Guard also determined that people died because they couldn’t quickly find their life preservers, which were buried under other gear, so it now requires racers to wear life jackets during the beginning of the race, on the assumption that even if removed, recently worn preservers will be close enough at hand.

Garner, the Fairhope Yacht Club’s former commodore, was dismissive of the Coast Guard’s investigation. “I’m assuming they know the right-of-way rules,” he said. “But as far as sailboat racing, they don’t know squat.”

Like many races in the U.S., the regatta was governed by the rules of U.S. Sailing, whose handbook for race organizers is unambiguous: “If foul weather threatens, or there is any reason to suspect that the weather will deteriorate (for example, lightning or a heavy squall) making conditions unsafe for sailing or for your operations, the prudent (and practical) thing to do is to abandon the race.” The manual outlines the responsibility of the group designated to run the race, known as the race committee, during regattas in which professionals and hobbyists converge: “The race committee’s job is to exercise good judgment, not win a popularity contest. Make your decisions based on consideration of all competitors, especially the least experienced or least capable competitors.”

The family of Robert Thomas is suing the yacht club for negligence and wrongful death. Thomas, who worked on boats for Robert Delaney, doing carpentry and cleaning jobs, had never stepped foot on a boat in water, but was invited by Delaney to come along for the regatta. Both men died when the boat flipped over and pinned them underneath.

Omar Nelson, an attorney for Thomas’ family, likens the yacht club to a softball tournament organizer who ignores a lightning storm during a game. “You can’t force the players to go home,” he said. “But you can take away the trophy, so they have a disincentive.” The lawsuit also alleges that the yacht club did in fact initially cancel the race due to the storm, contrary to Garner’s claim about a misunderstanding about the scratch sheet, but that the organizers reversed their decision. The yacht club’s current commodore, Randy Fitz-Wainwright, declined to comment, citing the ongoing litigation. The club’s attorney also declined to comment.

For its part, the Coast Guard, according to an internal memo about its investigation obtained by Smithsonian , notes that the race’s delayed start contributed to the tragedy. “This caused confusion among the race participants and led to a one-hour delay....The first race boats finished at approximately 1350. At approximately 1508, severe thunderstorms consisting of hurricane force winds and steep waves swept across the western shores of Mobile Bay.” The Coast Guard has yet to release its report on the disaster, but Cederholm said that, based on his experience as a search-and-rescue expert, “In general, the longer you have boats on the water when the weather is severe, the worse the situation is.”

For many of the sailors themselves, once their boats were rigged and they were out on the water, it was easy to assume the weather information they had was accurate, and that the storm would behave predictably. Given the access that racers had to forecasts that morning, Thornton, the meteorologist, said, “The best thing at that point would be to stay home.” But even when people have decent information, he added, “they let their decision-making get clouded.”

“We struggle with this,” said Bert Rogers, executive director of Tall Ships America, a nonprofit sail training association. “There is a tension between technology and the traditional, esoteric skills. The technology does save lives. But could it distract people and give them a false sense of confidence? That’s something we’re talking about now.”

Hana, who had kept her spirits buoyed with jokes in the midst of the ordeal, said the full seriousness of the disaster only settled on her later. “For a year and a half I cried any time it rained really hard,” she said. She hasn’t been back on the water since.

Lennard went back to the water immediately. What bothers him most is not the power of the storm but rather the power of numerous minute decisions that had to be made instantly. He has re-raced the 2015 Dauphin Island Regatta countless times in his mind, each time making adjustments. Some are complex, and painful. “I shouldn’t have left Mr. Brown to go find my dad,” he said. “Maybe if I had stayed with him, he would be OK.”

He has concluded that no one decision can explain the disaster. “There were all these dominoes lined up, and they started falling,” he said. “Things we did wrong. Things Fairhope Yacht Club did wrong. Things that went wrong with the boat. Hundreds of moments that went wrong, for everyone.”

In April of this year, the regatta was postponed because of the threat of inclement weather. It was eventually held in late May, and Lennard entered the race again, this time with Scott Godbold’s son, Matthew.

During the race, somewhere near the middle of the bay, their boat’s mast snapped in high wind. Scott Godbold had shadowed them, and he pulled alongside and tossed them a tow line.

Lennard was still wearing his life preserver.

Editor’s note: an earlier version of this story used the phrase “60 knots per hour.” A knot is already a measure of speed: one knot is 1.15 miles per hour.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Bryan Schutmaat | READ MORE

Bryan Schutmaat is a photographer whose work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine , Bloomberg Business Week , and The Telegraph . He has two books of photography, Islands of the Blest and Grays the Mountain Sends .

Matthew Teague | READ MORE

Matthew Teague is a freelance writer in Fairhope, Alabama. He has also written for Esquire , where he won a National Magazine Award in 2016.

Seattle sailor dies in accident at Race Week 2021 off Anacortes

Seattle sailor Greg Mueller, a member of the With Grace sailing team, died on Tuesday afternoon in a boating accident. Mueller, 58, fell overboard during a race in the Race Week 2021 regatta held in Anacortes this week.

Mueller was the team’s foredeck, the crew member responsible for controlling sail hoists and drops and preparing for spinnaker hoists, gybes and drops. According to Chris Johnson, the With Grace skipper, Mueller accidentally stepped into a line that looped around his foot right as the spinnaker filled. As the sheet filled with air, Johnson said, it jerked Mueller off the boat, where he dangled upside down by his foot, about 8 to 10 feet in the air, before plunging into the water where he was dragged alongside the boat, still connected by the line.

Crew members rushed to bring him back on board, where they took turns performing CPR, while another teammate of the eight-person crew called the race committee to get help.

Several team members aboard the vessel had completed Safety at Sea training provided by the Coast Guard, Johnson said, but there was little more they could do except call for medical attention.

Johnson said Mueller had spent two to three minutes in the water by the time his crew could slow the boat enough to bring him back aboard the ship. Though he was wearing a personal flotation device, it was of little use because of the way he was positioned in the water.

Two boats from the race committee arrived to assist, but they had no medical personnel on board, according to crew members. Eventually, a speedboat came to take Mueller to Guemes Island, where a medical team received him.

The crew was uncertain whether Mueller still was alive when the speedboat arrived. They received a call shortly afterward with the news he had died.

Race Week event producer Schelleen Rathkopf confirmed Mueller’s death on Tuesday with a post on the notice board for Race Week Anacortes on yachtscoring.com.

“We are all deeply saddened to have lost a fellow racer, and my condolences go out to the crew’s family, friends, and fellow racing comrades,” Rathkopf said in a news release issued Thursday.

The Skagit County coroner’s office said an autopsy was scheduled for Friday and that it would release information on the cause of death Monday afternoon.

Johnson said Mueller had been a member of the With Grace crew since the purchase of the boat in 2014.

“Greg was a very key part of our team,” said crewmate Ken Jones. “He knew exactly when the sail should be changed and what size to use. He could predict problems and gave us clear directions. There are a lot of lines that have to be led just perfectly. Most of us had no idea what he did; everything was done for us, and we really relied on him.”

According to Jones, the With Grace team was made up of highly skilled sailors. There had been no mishap or breakage on the boat Tuesday; he said what happened was a complete accident.

“I appreciated his contribution to the team,” Johnson said. “He always showed up for races and was very consistent, even in terrible weather.”

A longtime member of the Washington Yacht Club, Mueller was an avid racer, and he participated in frequent races throughout the Seattle area, including the famed annual Duck Dodge on Lake Union.

His preferred vessel was the keelboat, which is a typically longer boat ranging from 20 to 30 feet long. Mueller also enjoyed cycling and would ride to the dock for races, often wearing shorts on deck, having come straight from his bike, his crewmates said.

Leo Sergio Morales, a fellow member of the Washington Yacht Club, said Mueller loved bringing new members to the club and he taught students to sail keelboats. He would often take the club’s J22 boat out to race on Lake Washington, bringing along students who wanted more race experience.

“He was great about including other people,” said Raz Barnea, another Washington Yacht Club friend. “The club really places emphasis on students who wouldn’t otherwise have the opportunity to sail, and Greg helped a lot of people get their sea legs.”

Mueller’s ability to perform well in races on the J22, a heavy boat not always intended for the sort of races he’d enter, was a testament to his skills, his friends said.

“It’s a shock and a loss,” said Morales. “He was a fixture in the sailing community here in Seattle.”

Friends and crewmates described Mueller as a highly competent sailor and a quiet, unassuming person in a sport that can draw some big egos.

“Sailing accidents can happen to anybody,” said Barnea. “When they happen to someone as skilled as Greg, it really puts it into perspective that something can go wrong.”

Seattle Times news researcher Miyoko Wolf contributed to this story.

Most Read Life Stories

- What to do if you see a bear, cougar or coyote on a WA trail

- Kick your halibut up a notch with crunchy pistachios and smoky harissa

- Seattle Restaurant Week's best deals, intriguing new spots, and old favorites

- Summer travel trends 2024: More crowds and expensive airfare, hotels

- Should you eat, or avoid, nitrates? It depends on where they come from

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

WEATHER ALERT

A rip current statement in effect for Coastal Broward and Coastal Miami Dade Regions

At least 2 hurt after racing boat crashes, partially sinks in biscayne bay.

Roy Ramos , Reporter

CORAL GABLES, Fla. – First responders took at least two men to a local hospital following a boat crash in Biscayne Bay Friday morning, according to Coral Gables police.

The crash happened sometime before 10:30 a.m., according to fire dispatch records.

Images from Sky 10 showed the catamaran racing boat sinking about a mile east of Matheson Hammock Park.

Medics took the victims to Jackson Memorial Hospital, police said. One of the victims had severe injuries and was taken to JMH as a trauma alert patient.

Josue Rodriguez, a friend of the victims, said he was in the process of taking his boat out to meet them when the crash happened. He said the two are experienced with speedboats.

“He knew what he was doing and the day was calm and something must have gone wrong,” Rodriguez told Local 10 News in Spanish, saying he didn’t know what led up to the crash.

Amid calm waters, Rodriguez said something must have malfunctioned with the boat.

A fisherman told Local 10 News that the water in the area is only about 11 feet deep.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission is now investigating and has not released any information about a suspected cause.

Approximate location:

Copyright 2023 by WPLG Local10.com - All rights reserved.

About the Author

Roy Ramos joined the Local 10 News team in 2018. Roy is a South Florida native who grew up in Florida City. He attended Christopher Columbus High School, Homestead Senior High School and graduated from St. Thomas University.

Local 10 News @ 11PM : Apr 16, 2024

Local 10 news @ 6pm : apr 16, 2024, local 10 news @ 5pm : apr 16, 2024, local 10 news @ 4pm : apr 16, 2024, house republicans deliver impeachment charges to alejandro mayorkas.

FWC: Woman killed Sunday in boating accident at Lake Iamonia in Leon County

T ALLAHASSEE, Fla. (WCTV) - A 27-year-old woman was killed Sunday afternoon in a boating accident, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC).

The fatal boating accident happened at about 5 p.m. at Lake Iamonia in Leon County, north of the capital city, FWC investigator and public information officer Travis Basford said. The wreck involved two vessels, one of which was an airboat, he said. The Leon County Sheriff’s Office and emergency medical responders assisted FWC at the scene.

The airboat was damaged to the starboard side of the vessel and the propeller cage. Both boats have been seized for investigative purposes, according to a press release by FWC. Public information director, Faith Flawn said there were four people in each boat, but there is no information on whether anyone else was injured in the incident.

Co-owner of Sunshine Boats and Motors, Peter Magnuson said he’s been boating all his life and only had one word to describe Sunday’s crash.

“Tragic,” Maguson said. “Somebody was going for a nice day on the water and that was it. Just tragic and I’m sure it was preventable in some way or another.”

With the weather warming up and more people going to local lakes and rivers, it’s important to keep safety first the boater said.

“Pay attention to your surroundings and know where you’re going, know what you’re doing and know your equipment,” Maguson said.

The business owner also said it’s important to wear a life jacket and safety lanyard and know which side to pass when approaching another boat.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story said a 28-year-old woman died in the boat crash, based on FWC reporting. They have since amended their statement and said she was 27.

To stay up to date on all the latest news as it develops, follow WCTV on Facebook and X ( Twitter ).

Have a news tip or see an error that needs correction? Write us here . Please include the article's headline in your message.

Keep up with all the biggest headlines on the WCTV News app. Click here to download it now.

Wrongful death lawsuit filed in connection with fatal boat crash in Boston Harbor in 2021

The family of Jeanica Julce , a 27-year-old Somerville woman who was killed in a boat crash in Boston Harbor in July 2021, filed a wrongful death lawsuit on Monday against the operator of the vessel, who is also charged criminally in connection with the fatal outing, according to legal filings.

Julce’s family filed a $15 million suit in Suffolk Superior Court against Ryan Denver, the owner and operator of the vessel named “Make It Go Away,” which Julce and several other passengers were on when it crashed into a navigational marker off Castle Island around 3 a.m. on July 17, 2021, court records show.

A second named defendant in the lawsuit was Lee Rosenthal, a Beverly resident who was operating a boat that allegedly hit Julce in the water after “Make It Go Away” had capsized, according to the civil complaint.

“The filing includes a false accusation regarding Mr. Rosenthal who was found to have no responsibility or involvement by police detectives and rescue personnel who investigated the fatal accident,” Rosenthal’s lawyer, Kevin G. Kenneally, said in a statement. “The at-fault party was charged. The authorities confirmed in the investigation that an individual in the water who was not the victim asked Mr. Rosenthal to look for the young woman, which he did. According to the official police reconstruction, Mr. Rosenthal then ‘transited away to not interfere with the rescue’ as police and fire boats arrived.”

Denver has pleaded not guilty to criminal charges of manslaughter, assault and battery with a dangerous weapon, and assault and battery with a dangerous weapon causing serious injury. His trial is scheduled for February in Suffolk Superior Court, records show.

“Since the day of this tragic accident, Ryan Denver has said that he operated his boat in a reasonable manner and at an appropriate speed, while sober,” his lawyer, Michael Connolly, said in a statement Tuesday. “The navigational marker which his boat hit was poorly illuminated and obscured by dredging operations. After the impact, Ryan and his passengers entered the harbor as the boat began taking on water. Ryan did everything in his power to assist them until first responders arrived on the scene and he has cooperated fully with law enforcement since.”

Advertisement

In the civil complaint, Julce’s family said she was one of eight people on Denver’s boat at the time of the crash.

Denver “operated his vessel in a negligent, grossly negligent, and/or reckless manner so as to strike an immovable navigation device, Daymarker #5, in Boston Harbor,” causing the boat to capsize, the lawsuit alleged.

The lawsuit said Denver, a Seaport resident, had consumed alcohol that night.

Connolly, however, said Tuesday that there was no evidence developed during the grand jury investigation that Ryan was impaired that evening. Additionally, the boat was not speeding, and the issue of speed was excluded from the criminal case by a Superior Court judge.”

Denver, Connolly said, “entered a plea of not guilty and we have every expectation that once presented with all of the evidence a jury will exonerate him.”

At the time of the crash, Denver was “operating his vessel at an unsafe speed” and “failed to use and heed his navigational instruments” when he struck the marker, the lawsuit alleges.

After the crash, the boat skippered by Rosenthal arrived before any emergency vessels, according to the lawsuit. As it was circling the area, it hit Julce, who had been swimming toward the boat, the lawsuit alleged.

Rosenthal has not been charged criminally in connection with the crash. But in 2022, his lawyer said in related federal civil proceedings that investigators had determined that Rosenthal “was not at fault but simply ‘transited away from the area to not interfere’ with the official federal, state and local rescue vessels coming to the scene.”

Julce’s body was recovered from the water shortly after 10 a.m., according to authorities.

The suit said Julce would not have died but for the “negligence, gross negligence, and/or recklessness” of Denver and Rosenthal.

In the days after her death, her family remembered her as a kindhearted person.

“My sister was beautiful in every way,” her sister, Latoya Julce, told The Boston Globe. “She could always find a way to make anyone feel better or confident about themselves. I’m not understanding how she’s the only one that didn’t make it.”

She said her sister, “the light in our family,” was with friends on the boat, and that she was often on the boat.

Her father, Wilfred Julce, said she studied at the University of Massachusetts Boston. She loved to dance and planned to open a studio, he said.

He described his daughter as outgoing and ambitious, someone who “loved life.”

“She was always smiling, laughing. She was a people person. Ask anybody,” he said.

Shortly after the crash, Denver released a statement describing Julce as a close friend.

“I am incredibly saddened by the loss of my dear friend this weekend in a boating accident on Boston Harbor. My deepest sympathies are extended to Jeanica’s family,” Denver said. “I am thankful to those first responders who came to our aid and will cooperate with their follow-up to our rescue.”

Also on Monday, another passenger on the “Make It Go Away” at the time of the crash, Aristide Lex, filed a separate lawsuit against Denver, listing more than $300,000 in damages.

Lex suffered “serious and severe personal injuries” including “permanent injuries and disfigurement,” when he was thrown from the boat, the suit alleged.

The suit said Lex incurred “significant medical expenses and costs, and incurred lost wages, as well as impairment of his earning capacity and future medical costs associated with his care and attendance.”

This story has been updated.

Travis Andersen can be reached at [email protected] .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Boat Capsized Paul was ondeck and lost other crew member was below deck. [11] Doublehanded Lightship Race. Island Yacht Club of Alameda. 16 March 2008. Matthew Gale (USA), 68, Mill Valley, California. Anthony Harrow (USA), 72, Larkspur, California.

The Ocean Race 2022-23 Race Schedule: Alicante, Spain - Leg 1 (1900 nm) start: January 15, 2023 Cabo Verde - ETA: January 22; Leg 2 (4600 nm) start: January 25

The leading boat in The Ocean Race dropped out of the last leg of the around-the-world sailing competition on Friday and asked the sport's overseers for compensation in the standings to make up for the collision that punctured its carbon fiber hull.. Six months after leaving Spain on a 32,000-nautical mile (37,000-mile, 59,000-km) circumnavigation of the globe, 11th Hour Racing was T-boned ...

PORTSMOUTH, R.I. (August 6, 2012) - A US Sailing independent review panel has released the report on its investigation of the sailing accident that occurred on April 14, 2012 during the Full Crew Farallones Race out of San Francisco, Calif. The accident resulted in the deaths of five sailors from the sailboat, Low Speed Chase .

TARANTO, ITALY - June 6, 2021 - The United States SailGP Team's bid to win the Italy Sail Grand Prix in Taranto ended today in dramatic fashion when on the penultimate leg of the final race the team's F50 catamaran struck an unidentified, submerged object.. The team was comfortably leading the Italy Sail Grand Prix final podium race, in sight of the finish line, at the time of the ...

Dramatic video footage shot from on-board Japan SailGP as their courses intersected with USA SailGP on Leg 3 of Race 4 of Day 2 of SailGP Bermuda. Skipper Nathan Outteridge (JPN) wanted to duck behind the US boat which was on starboard and holding right of way. They were in mid-fleet with Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand ahead.

The crash ruled both boats out of the rest of the day's racing and also led to the US boat capsize shortly afterwards. It was the first event for Jimmy Spithill, helmsman and America's Cup winner ...

The hopes of 11th Hour Racing Team of winning The Ocean Race 2022-23 suffered a big blow as they were left with damage to their boat following a crash with GUYOT environnement - Team Europe.

Dramatic footage of the collision between Gladiator Sailing Team and Sled in today's 52 Super Series Miami Royal Cup.Video Credit: Ben Durham

Two boats collided just 17 minutes into the final, 10-day leg of the around-the-world Ocean Race on Thursday, sending first-place 11th Hour Racing back to port in The Hague, the Netherlands, with a gaping hole in its carbon fiber hull.. The Newport, Rhode Island-based boat filed a protest against Guyot environnement - Team Europe, which punctured the port side of the 11th Hour hull with its ...

Gilmore, the owner of the Uncontrollable Urge, tweeted Friday that he was taking the new boat on its first race, and noted that the forecast called for 25-knot winds. "Gonna see what this boat can do!" he tweeted. Hope said the Uncontrollable Urge was known within the sailboat racing circuit and that its crew and skipper were experienced.

The 30-foot sailboat was competing in the Islands Race when the vessel's rudder failed around 9:30 p.m. The crew tried to launch but couldn't because of weather conditions.

July 2017. Michael Byers. The morning of April 25, 2015, arrived with only a whisper of wind. Sailboats traced gentle circles on Alabama's Mobile Bay, preparing for a race south to the coast. On ...

Seattle sailor Greg Mueller, a member of the With Grace sailing team, died on Tuesday afternoon in a boating accident. Mueller, 58, fell overboard during a race in the Race Week 2021 regatta held ...

Sailing is notably safe among adventure sports, so safe, in fact, there may be a tendency to regard serious accidents as anomalous freaks from which little can be learned. This is a mistake. One of the most important turning points in our sport came when a gale widely described as "freakish" decimated the Fastnet Race fleet in August 1979.

Fatal Accidents during offshore powerboat racing. "Weirwolf" a 23 ft Whitehorse powered by 2 x 175 hp Mercury outboards. Boat nose dived into a wave and broke in half. Co-driver Michael Meeng escaped uninjured. [51] [53] Pironi was previously a Formula One racing driver for Ferrari.

My sailing gloves: http://amzn.to/2d8o0leFoul Weather Pants: http://amzn.to/2dmHOM4Sailing Boots: http://amzn.to/2dmKJnQHi Vis Bibs: http://amzn.to/2cDhQ...

The boat was participating in the Race World Offshore World Championship, which ends Sunday. Some of the boats can reach speeds of up to 160 mph, according to the Monroe County Tourist Development ...

Sail Yacht crash compilation 2020 - fail - crash - fowl weather - fireSome random yacht videos from the internet, includin crane capsizing, a brand new j-cla...

CORAL GABLES, Fla. - First responders took at least two men to a local hospital following a boat crash in Biscayne Bay Friday morning, according to Coral Gables police. The crash happened ...

Wanna go Boating Safely? Visit: http://www.richielottoutdoors.comBoat Crashes in Rough Seas, Boat wrecks, ship wrecks, boat accidents and more. Boats and shi...

The father of a Somerville woman killed in a boat crash in Boston Harbor is suing for $15 million in a wrongful death lawsuit. Ryan Denver from Boston was arraigned at Suffolk Superior Court in 2021.

The fatal boating accident happened at about 5 p.m. at Lake Iamonia in Leon County, north of the capital city, FWC investigator and public information officer Travis Basford said.

SAIL CRASHES - Boat Crash, Sailboat Racing, Sailing Fails 2021 Special Compilation#SailCrash #BoatCrash #Capsizes

The family of Jeanica Julce, a 27-year-old Somerville woman who was killed in a boat crash in Boston Harbor in July 2021, filed a wrongful death lawsuit on Monday against the operator of the ...

Please Like And Subscribe To My YouTube Channel Thank You.Epic Speed Boat Crashes And Smashes Compilation 2019Here is a collection of speed boat thrills and ...