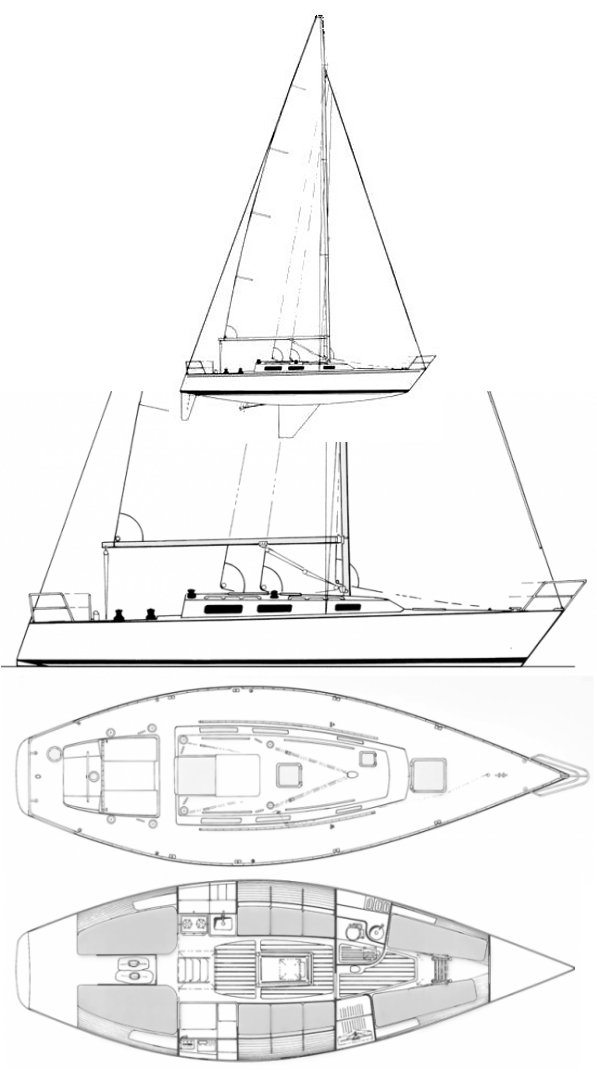

The J36 is a 35.95ft fractional sloop designed by Johnstone and built in fiberglass by J Boats between 1981 and 1984.

55 units have been built..

The J36 is a light sailboat which is a very high performer. It is very stable / stiff and has a low righting capability if capsized. It is best suited as a racing boat. The fuel capacity is originally small. There is a very short water supply range.

J36 for sale elsewhere on the web:

Main features

Login or register to personnalize this screen.

You will be able to pin external links of your choice.

See how Sailboatlab works in video

We help you build your own hydraulic steering system - Lecomble & Schmitt

Accommodations

Builder data, modal title.

The content of your modal.

Personalize your sailboat data sheet

Review of J/36

Basic specs..

The boat is typically equipped with an inboard Yanmar diesel engine.

Sailing characteristics

This section covers widely used rules of thumb to describe the sailing characteristics. Please note that even though the calculations are correct, the interpretation of the results might not be valid for extreme boats.

What is Theoretical Maximum Hull Speed?

The theoretical maximal speed of a displacement boat of this length is 7.4 knots. The term "Theoretical Maximum Hull Speed" is widely used even though a boat can sail faster. The term shall be interpreted as above the theoretical speed a great additional power is necessary for a small gain in speed.

The immersion rate is defined as the weight required to sink the boat a certain level. The immersion rate for J/36 is about 224 kg/cm, alternatively 1256 lbs/inch. Meaning: if you load 224 kg cargo on the boat then it will sink 1 cm. Alternatively, if you load 1256 lbs cargo on the boat it will sink 1 inch.

Sailing statistics

This section is statistical comparison with similar boats of the same category. The basis of the following statistical computations is our unique database with more than 26,000 different boat types and 350,000 data points.

What is L/B (Length Beam Ratio)?

Maintenance

Are your sails worn out? You might find your next sail here: Sails for Sale

If you need to renew parts of your running rig and is not quite sure of the dimensions, you may find the estimates computed below useful.

This section shown boat owner's changes, improvements, etc. Here you might find inspiration for your boat.

Do you have changes/improvements you would like to share? Upload a photo and describe what to look for.

We are always looking for new photos. If you can contribute with photos for J/36 it would be a great help.

If you have any comments to the review, improvement suggestions, or the like, feel free to contact us . Criticism helps us to improve.

J/36 Detailed Review

If you are a boat enthusiast looking to get more information on specs, built, make, etc. of different boats, then here is a complete review of J/36. Built by J Boats and designed by Rod Johnstone, the boat was first built in 1981. It has a hull type of Fin w/spade rudder and LOA is 10.96. Its sail area/displacement ratio 22.07. Its auxiliary power tank, manufactured by Yanmar, runs on Diesel.

J/36 has retained its value as a result of superior building, a solid reputation, and a devoted owner base. Read on to find out more about J/36 and decide if it is a fit for your boating needs.

Boat Information

Boat specifications, sail boat calculation, rig and sail specs, auxillary power tank, accomodations, contributions, who designed the j/36.

J/36 was designed by Rod Johnstone.

Who builds J/36?

J/36 is built by J Boats.

When was J/36 first built?

J/36 was first built in 1981.

How long is J/36?

J/36 is 9.3 m in length.

What is mast height on J/36?

J/36 has a mast height of 14.33 m.

Member Boats at HarborMoor

How Much Does A Sailboat Weigh?

Last Updated by

Daniel Wade

June 15, 2022

While it may seem counterintuitive, there's more than one weight measurement for sailboats. In this article, we'll go over three ways of determining the weight of a sailboat.

Consumer sailboats usually weigh between 120 and 30,000 pounds, with the average sailboat weighing 8,845 pounds. This average sailboat weight is without taking into account additional gear, fuel, people, and more that are on a sailboat out on the water. To accurately weigh a boat isn't as simple as dropping it on a scale. Besides the logistical problems you'd face, it wouldn't give you all the information you need to know.

That's why there are a few types of weight measurement for boats. These are dry weight, displacement, and tonnage. Don't confuse these subtypes; while displacement and dry weight are closely related, tonnage is a different type of measurement.

Table of contents

Dry weight is closely related to displacement, and it’s the number you’d get if you hung an empty boat from a scale. Dry weight isn’t always included on specification sheets, but it’s vital if you intend to tow or transport your boat.

To give you a better idea of the dry weight of different vessels, we’ll use a short list of common boat sizes by LOA (length overall) in feet. Keep in mind, the weight of a boat differs based on hull material , mast type, and many other factors.

- Dinghies (less than 12’): 100 to 200 pounds

- Small Sailboats (15’ to 20’): 400 to 2,500 pounds

- Medium Sailboats (21’ to 25’): 2,500 to 5,000 pounds

- Cruising Sailboats (27’ to 32’): 7,000 to 12,000 pounds

- Large Sailboats (35’ to 40’): 12,000 to 30,000 pounds

What factors contribute to the weight of a sailboat? Hull material makes a huge difference in dry weight. Older wooden cruising vessels with deep keels often weigh thousands of pounds more than an equivalent-sized fiberglass boat. Also, sport and racing sailboats sometimes weigh a fraction of an average consumer cruiser.

A sailboat’s mast and rigging contribute to the weight as well. Solid hardwood masts sometimes weigh hundreds of pounds more than hollow masts, and heavy brass deck equipment adds up. It doesn’t take long for equipment to increase the weight of a boat.

Displacement

How is displacement different than dry weight? First of all, you can only calculate dry weight when a boat is empty and dry. Displacement is equal to the weight of a boat, along with everything (and everyone) aboard at the time of measurement. This includes water, fuel, deck equipment, interior cushions—you get the picture.

The most common measurement of weight for sailboats is displacement, and it reflects the weight of a loaded sailboat in the water. We measure displacement by calculating the weight of the water volume a boat displaces. This unit is vital in boat design. A vessel will sink if it weighs more than the water it displaces.

There’s a simple way of picturing the concept of displacement. Imagine a cup of water filled to the very top. Now drop in a coin and measure the amount of water that spills out. The weight of the spilled liquid is the displacement of the coin.

Oddly, the displacement value of a boat means slightly different things in salt and freshwater. Saltwater weighs 64.1 pounds per cubic foot, while fresh water weighs 62.4 pounds per cubic foot. That means a boat will displace more freshwater because saltwater essentially ‘pushes harder’ upward on the craft.

So, how does displacement translate to weight? You can get a general idea of how ‘heavy’ a boat is using a simple calculation, shown below.

(Displacement/2,240) / (LWL x 0.02)^3

1) First, you’ll need to convert the displacement (in pounds) to long tons . Simply divide the displacement by 2,240 to get your answer. Put this number aside for a moment.

2) Next, find the length at waterline ( LWL ) of your boat, and multiply it by 0.01 . Take this value and raise it to the power of 3 . It should look something like this: (LWL x 0.01) ^3

3) Finally, divide your first number (in long tons) by the result of the previous calculation to get your displacement to length ratio .

The displacement to length ratio is useful for a number of reasons. Using this simple number allows you to determine the weight class of a boat, so you’ll know what it’s suitable for. Below, we put together a list to help you understand the differences using a D/L ratio of 40 to 400.

- Ultra-light (race boats): 40 to 89

- Light (race or trailer-sailboat): 90-179

- Medium (day boat/light cruiser): 180-269

- Heavy ( cruising sailboat /offshore cruiser): 270-359

- Very Heavy (heavy offshore cruiser): 360-400+

Generally speaking, sailboats built before 1950 typically have a heavy D/L ratio. A boat with a ratio over 300 handles much differently than a light vessel, and many consider heavier boats to be more ‘seaworthy.’ Of course, it’s not always that simple, but the general rule still applies. Using what we know about displacement, it’s time to go over our final weight measurement.

Tonnage represents the volume of the enclosed space on a boat, using the same concept as displacement. Salt and freshwater tonnage differ for the same reasons as well. Tonnage and size are directly related, and this unit gives you an idea of how much cargo you can carry before overloading. Cargo tonnage is measured in long tons, similar to displacement. Simply divide the tonnage (in pounds) by 2,240 to get your cargo tonnage value.

Why Weight Matters

While we haven’t mentioned every way of weighing a sailboat, you can gain a lot from understanding dry weight, displacement, and tonnage. For example, you’ll need to know the dry weight of a boat to determine if your vehicle can actually tow it. If a vessel weighs 15,000 pounds, you’ll probably want to avoid it unless you have a permanent mooring or a heavy-duty pickup truck.

Displacement and dry weight are closely related. Displacement is equally crucial for determining a boat’s capabilities. Heavy, deep-keel sailboats generally handle well in rough seas, but you probably won’t be racing with a high D/L ratio. If you understand what your intentions for a boat, it’s imperative to comprehend displacement and D/L ratio.

Tonnage is essential to understand, especially for offshore cruising. Using this value, you can calculate how much food, water, supplies, and how many people you can take aboard. Ignoring any of these values can spell disaster for any captain but understanding sailboat weight ahead of time ensures you’ll know what you’re doing.

Now that you have a grasp of sailboat weight measurements, it’s time for some real-world examples. We found the specifications of three common sailboats so you can get an idea of what to expect.

How Much Does A Catalina 30 Weigh?

This 30-foot sloop is one of the most successful production fiberglass sailboats in history. It was built by Catalina Yachts between 1972 and 2008, with over 6,000 units. We chose the Catalina 30 because it’s an ideal example of a medium-sized all-purpose cruising sailboat . This versatile sloop is well suited for coastal cruising and some offshore passages.

Dry weight clocks in at 10,200 pounds, with a D/L ratio of 291.43. This sailboat is an ideal general-purpose cruising vessel.

How Much Does An O’Day 25 Weigh?

Despite being only a few feet shorter than the Catalina 30, the O’Day 25 is a much different boat. This popular day cruiser has a displacement of only 4,007 pounds, which is less than half of the Catalina 30. The O’Day 25 falls into the medium weight category with a D/L ratio of only 193.16. Comparatively, you can immediately see how these two common fiberglass boats differ. The O’Day 25 will be much easier to tow, yet less suitable for long offshore passages.

How Much Does An Atkin ‘Eric’ 32 Weigh?

This 32-foot wooden sailboat was designed decades ago for offshore sailing. While dimensionally similar to the Catalina 30, this boat is significantly heftier with a displacement of 19,500 pounds. Despite only being 2-feet longer than our Catalina at the waterline, the Atkin Eric has a D/L ratio of 418.81 making it an extremely heavy boat!

From a distance, all three of our examples would look similar in size and above-water characteristics. Below the surface, we find something very different. Each of these vessels is suitable for different things, and how much they weigh plays a vital role in their uses. Now that you know how to interpret the weight of a sailboat, you’ll be prepared to choose one that best fits your needs.

Related Articles

I've personally had thousands of questions about sailing and sailboats over the years. As I learn and experience sailing, and the community, I share the answers that work and make sense to me, here on Life of Sailing.

by this author

Learn About Sailboats

Most Recent

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

October 3, 2023

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

Affordable Sailboats You Can Build at Home

September 13, 2023

Best Small Sailboat Ornaments

September 12, 2023

Discover the Magic of Hydrofoil Sailboats

December 11, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies. (866) 342-SAIL

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

- Forums New posts Unanswered threads Register Top Posts Email

- What's new New posts New Posts (legacy) Latest activity New media

- Media New media New comments

- Boat Info Downloads Weekly Quiz Topic FAQ 10000boatnames.com

- Classifieds Sell Your Boat Used Gear for Sale

- Parts General Marine Parts Hunter Beneteau Catalina MacGregor Oday

- Help Terms of Use Monday Mail Subscribe Monday Mail Unsubscribe

J36 BALSA CORED HULL ?

- Thread starter Gill

- Start date Jan 7, 2007

- Forums for All Owners

- Ask All Sailors

I am thinking of purchasing a "81 J36 with some water intrusion around the rudder post into the balsa core. I believe the area to be 3' in diameter max. The area compromised is above the waterline and I think I can cut out the inner liner, recore the affected areas and lay up the liner. Anyone have any experience with this or any ideas?

- This site uses cookies to help personalise content, tailor your experience and to keep you logged in if you register. By continuing to use this site, you are consenting to our use of cookies. Accept Learn more…

Sail area calculations

Mainsail Area = P x E / 2 Headsail Area = (Luff x LP) / 2 (LP = shortest distance between clew and Luff) Genoa Area 150% = ( 1.5 x J x I ) / 2 Genoa Area 135% = ( 1.35 x J x I ) / 2 Fore-triangle 100% = ( I x J ) / 2 Spinnaker Area = 1.8 x J x I

Copyright � 2008 Sailboat Rig Dimensions All Rights Reserved.

Pulling together: how Cambridge came to dominate the Boat Race – a photo essay

The race along the River Thames between England’s two greatest universities spans 195 years of rivalry and is now one of the world’s oldest and most famous amateur sporting events. Our photographer has been spending time with the Cambridge University Boat Club over the past few months as they prepare for 2024’s races

T he idea of a Boat Race between the two universities dates back to 1829, sparked into life by a conversation between Old Harrovian schoolfriends Charles Merivale, a student at the time at St John’s College Cambridge, and Charles Wordsworth who was at Christ Church Oxford. On 12 March that year, following a meeting of the newly formed Cambridge University Boat Club, a letter was sent to Oxford.

The University of Cambridge hereby challenge the University of Oxford to row a match at or near London each in an eight-oar boat during the Easter vacation.

From then, the Cambridge University Boat Club has existed to win just one race against just one opponent, something Cambridge has got very good at recently. Last year the Light Blues won every race: the open-weight men’s and women’s races, both reserve races, plus both lightweight races – six victories, no losses, an unprecedented clean sweep. Cambridge women’s open-weight boat, or blue boat, has won the last six Boat Races while the men’s equivalent have won five out of the last seven. In such an unpredictable race, where external factors can play a large part, this dominance is startling.

Thames trials

Rough water as the two women’s boats make their way along the River Thames near Putney Embankment during the Cambridge University Boat Race trials.

It’s a mid-December day by the River Thames. The sky and water merge together in a uniform battleship grey and the bitter north wind whips the tops off the waves. Outside a Putney boathouse two groups of tense-looking women dressed in duck-egg blue tops and black leggings with festive antlers in their hair are huddling together, perhaps for warmth, maybe for solidarity. The odd nervous bout of laughter breaks out. For some of them this is about to be their first experience of rowing on the Tideway, a baptism of fire on the famous stretch of London water where the Boat Race takes place. “Perfect conditions,” remarks Paddy Ryan, the head coach for Cambridge University women, for this is trial eights day, when friends in different boats duel for coveted spots in the top boat.

A couple of hours later these women along with their male equivalents will have pushed themselves to the absolute limit, so much so that several of the men are seen trying to throw up over the side of their boats at the finish under Chiswick Bridge. This may be brutal but it’s just the start. For these students the next few months are going to be incredibly tough, balancing academic work with training like a professional athlete. Through the harshest months of the year they will be focused on preparing for the end of March and a very simple goal: beating Oxford in the Boat Race.

Agony for one of the men’s boats after the finish of the race near Chiswick Bridge during the Cambridge University Boat Race trials.

Ely early mornings

Two of the women’s boats head out in the early morning for a training session on the Great Ouse.

Early winter mornings on the banks of the Great Ouse, well before the sun has risen, can be pretty bleak. In the pitch black a batch of light blue minivans drop off the men and women rowers together at the sleek Ely boathouse that was opened in 2016 at the cost of £4.9m – it’s here that all Cambridge’s on-water training takes place. Very soon a fleet of boats carrying all the teams takes to the water for a training session that may last a couple of hours. Then it’s a quick change, a lift to the train station and back to Cambridge for morning lectures.

The women’s squad head into the Ely boathouse after a 6am drop-off.

As a rower descends the stairs to the bays where the boats are stored, there is a clear indication of why it was built and why they are there. “This is where we prepare to win Boat Races,” a sign says. Since this boathouse was built, Cambridge have won 30 of the 37 races across all categories.

Top: The men’s squad stretch in the boathouse before an early morning training session and a member of the men’s blue boat descends the stairs into where the boats are kept. Below: One of the men’s teams set off for early morning training and the women’s blue boat rows past the women’s lightweight crew during a training session.

It’s a far cry from the old tin sheds with barely any heating and no showers. These current facilities are impressive, enabling the entire men’s and women’s squads to be there at the same time and get boats out.

Top: The men’s blue boat prepare to derig their boat at their Ely training site. Above: The women’s blue boat put their vessel back in the boathouse after a training session on the Great Ouse.

But it’s not just the boathouse that has contributed so much, it’s also the stretch of water they train on. In a year when floods have affected so many parts of the country it has really come into its own. Paddy Ryan, the chief women’s coach, explains: “Along this stretch the river is actually higher than the surrounding land. The water levels are carefully managed by dikes and pumps. As a result we haven’t lost a single session to flooding. That’s not the case for Oxford. I believe their boathouse has been flooded multiple times this year, unable to get to their boats. We’ve had multiple storms but we’ve been able to row through them all.”

The men’s third boat practises on the Great Ouse.

It’s a flat, unforgiving landscape, especially in midwinter, definitely not the prettiest stretch of water, but Cambridge don’t care. Ryan says: “It might be a little dull on the viewing perspective but we could row on for 27km before needing to turn round. We have a 5km stretch that is marked out every 250m. We are lucky to have it.”

The men’s blue boat practise their starts on the long straight on the Great Ouse.

The sweat box

Members of the men’s squad check on their technique with the use of a mirror at the Goldie boathouse.

The old-fashioned Goldie boathouse is right in the centre of Cambridge perched on the banks of the River Cam. Built in 1873, its delicate exterior belies what goes on inside. This is the boat club’s pain cave, where the rowers sweat buckets, pushing themselves over and over again; it’s a good job the floor is rubberised and easy to wipe clean.

A wreath to Charles Merivale, the founder of the Boat Race, and wood panelling in the upstairs room at the Goldie boathouse which commemorates Cambridge crews that have competed in the Boat Race from 1829.

(Top) Seb Benzecry, men’s president of the Cambridge University Boat Club, and (above) Martin Amethier, a member of the reserve Goldie crew, sweat during sessions on ergo machines.

Iris Powell of the women’s blue boat (above) performs pull-ups during a training session.

Above left: Hannah Murphy, the cox of the women’s blue boat, urges on four of her crew (left to right) Gemma King, Megan Lee, Jenna Armstrong and Clare Hole, as they undertake a long session on the ergo machines. Above right: Kenny Coplan, a member of the men’s blue boat crew, looks exhausted then writes in his times after his session on an ergo machine (below).

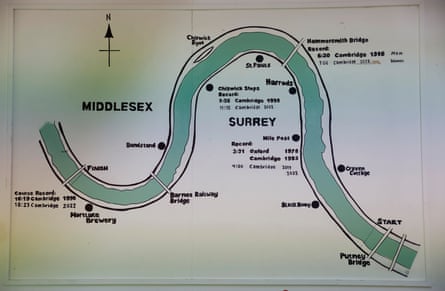

Brutal sessions on the various ergo machines, where thousands of metres are clocked and recorded, are a staple of the training regime set in place. If there is any slacking off the students just need to look up at one of the walls where a map of the Boat Race course hangs. The “S” shape of the Thames has been carefully coloured in the correct shade of blue and record timings for various key points on the course have been written in for both men and women. All but one record, and that one is shared, is held by Cambridge.

Paddy Ryan, the women’s chief coach, talks to the women’s blue boat during a training session on the River Great Ouse in February.

A key ingredient in any successful team is the coaching. Cambridge’s setup is stable and well established. Paddy Ryan is the chief women’s coach, a genial, tall Australian, he has been part of the women’s coaching team since 2013. The care and devotion to his squad is perfectly clear. “I have my notebook next to my bed so I can jot things down. I wake up in the middle of the night going: am I making the right decisions? I care about them as people and I need to manage them … We joke as coaches that we are teaching some of the smartest people on the planet how to pull on a stick.”

Rob Baker, the chief men’s coach, has Cambridge rowing in the blood. Born and bred in the city, his father was a university boatman for 25 years. He even married into the sport – his wife, Hayley, rowed for Cambridge as a lightweight – so it was no surprise that he became part of the coaching setup way back in 2001. He was the first full-time women’s coach in 2015 then moved to take over the men in 2018.

Rob Baker, the men’s chief coach, talks to his blue boat at their Ely training site.

Apart from an obvious role in the development of rowing skills, a key part of their job is making sure there is a balance for their student athletes. They understand they have to juggle training needs. “Every week we have a general plan,” says Baker, “but then someone might have an extra class or supervision they’ve got to do so we have to move around it. They are studying at one of the most competitive universities in the world with the highest standards so you’ve got to give them space to do that properly.” He goes on: “But when they get on the start line for their race, they’ll be just as competitive as if they were professionals.”

The presidents

Jenna Armstrong and Seb Benzecry discuss their plans in the Great Hall at Jesus College.

Every year one man and one woman are elected presidents to represent Cambridge University Boat Club. They are the captains and leaders, not only responsible for helping design the training programme in conjunction with the coaches but also making budgetary and tactical decisions along the way. This year both of them, Jenna Armstrong and Seb Benzecry, are from the same college, Jesus, which helps the communication between the two of them. They share ideas and knowledge, thoughts and worries. Their lives, for these intense few months, are a juggling act.

Armstrong is a 30-year-old from New Jersey, and doing a PhD in physiology. Once a very keen competitive junior skier she was forced to abandon her hopes of a career on the slopes after a number of serious knee injuries. She only started rowing in 2011 and only became aware of the Boat Race when she saw it on TV a couple of years later.

Jenna Armstrong, cycling down the Chimney, the grand entrance to Jesus College, to go to the other side of the city to carry out more of her PhD research at the department of physiology, development and neuroscience.

The research she carries out at the university labs could be turn out to be life-saving. “I study mitochondrial function in placentas from women from all over the world to learn how genetic and environmental factors during pregnancy can influence placental metabolism and impact the health of both mother and baby. I’m particularly interested in growth restriction which affects about 10% of babies worldwide. That can have lifelong implications for these babies and currently we don’t have any treatment for this.”

Benzecry, 27, is studying for a PhD in film and screen studies, and comes from a completely different rowing background. He grew up just a stone’s throw from the Boat Race course and went to a school on the banks of the Thames. This will be his 14th year of competitive rowing but his fourth and last Boat Race.

“ I remember one year my birthday fell on race day and we watched after my birthday party. Because we live fairly close to the course, I’ve always felt connected to the race.”

Seb Benzecry stands next to an Antony Gormley statue in the Quincentenary Library at Jesus College as he conducts research for his dissertation which forms part of his PhD in film and screen studies.

Talking about how hard it is to get the right balance between academic student life and rowing, Benzecry says: “I guess you have to accept there are many, many things you can’t do, you just don’t have time for during the season. You have to put the blinkers on.”

Armstrong says: “I have to be very prepared, very strategic and organised. I pack everything the night before, and then once I leave my room in the morning, I don’t go back. That allows me to go to training, go to the lab, go to training again. It’s surreal actually, to come to a place like Cambridge, have one of the best educations in the world on top of the most incredible rowing experiences in the world. We have a thing now in the boat, when we are doing something incredibly hard, I say this is my ideal Saturday, I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. I would rather be here than in bed or on a date. And I make everyone else say it with me too. I’d rather be nowhere else.”

Benzecry states: “When it’s really bad, when training is so hard, we say Oxford aren’t doing this, they could never do this. It’s an incredibly powerful thing to be thinking we work harder than them, our culture is better than them. They don’t want to go hard as we do – they might think they do but they don’t, they just don’t have it.”

Integration

The men’s and women’s blue boats during a training session on the River Great Ouse in February.

Until 1 August 2020, there were three separate university boat clubs in Cambridge: one for open-weight men, one for lightweight men, and one for open-weight and lightweight women. Since they merged to become one club, it has undoubtedly helped with everyone sharing the same resources and motivating and inspiring one another. No one is more important and everyone has a key part to play in the result. This year, Oxford have followed suit.

Baker says: “I definitely feel, for the athletes themselves, it makes a big difference. They all feel like they’re contributing to one common goal. Every cog in the wheel has to do its job but for sure it feels like one big team on a mission.”

Benzecry explains: “We’re seeing each other train, we’re all out on the water at the same time, we’re supporting each other throughout the season, building a sense of momentum for the whole club towards the races. Everyone’s just inspiring each other all the time and I think that’s been such a sort of cultural shift for Cambridge.”

The men’s blue boat pack their craft on to a trailer at their Ely training site ready for the trip down to London for the Boat Race.

Siobhan Cassidy, the chair of the Boat Race, knows from first-hand how the integration has helped. She rowed for the Light Blues in 1995 and had a key role in the transition. “We could see the advantages of working together, collaborating as a bigger team, the positive impact we felt that could have on performance. But not just the output, actually the whole experience for the young people taking part.”

Siobhan Cassidy, the chair of the Boat Race, pictured at the Thames Rowing Club at Putney Embankment.

This Saturday, if the weather holds, an estimated 250,000 people, the vast majority of whom have no allegiance to one shade of blue or the other, will pack the banks of the Thames to see these races. It’s one of the largest free events in Britain. Broadcast live on BBC One, the race is also beamed to 200 countries across the world.

The starting stone for the University Boat Race and pavement inscription: “The best leveller is the river we have in common” at Putney Embankment.

A map of the Boat Race course at the Goldie boathouse, with the Thames coloured in Cambridge blue and record timings written in for men and women showing almost total Cambridge dominance.

A sporting pinnacle being contested on a fast-flowing, unpredictable river by two teams of university students – it’s pretty bizarre. But maybe it’s that quirkiness that keeps the race, after almost two hundred years, still going strong. And even more bizarre to think that Cambridge, the current dominant force in the Boat Race, a sporting event that can’t shrug off its elitist stereotype, owes so much of that success to such egalitarian principles.

- The Guardian picture essay

- The Boat Race

- University of Cambridge

- Photography

Most viewed

How a cargo ship took down Baltimore’s Key Bridge

To bridge experts, the collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge after being hit by a heavy cargo ship was as inevitable as it was devastating.

When a vessel as heavy as the Singapore-flagged Dali crashes with such force into one of the span’s supercolumns, or piers, the result is the type of catastrophic, and heartbreaking, chain reaction that took place early Tuesday.

“If the column is destroyed, basically the structure will fall down,” said Dan Frangopol, a bridge engineering and risk professor at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania who is president of the International Association for Bridge Maintenance and Safety. “It’s not possible to redistribute the loads. It was not designed for these things.”

No bridge pier could withstand being hit by a ship the size of the Dali, said Benjamin W. Schafer, a professor of civil and systems engineering at Johns Hopkins University.

“These container ships are so huge,” Schafer said. “That main span has two supports. You can’t take one away.” He called the accident “a huge infrastructure failure,” but not because of the bridge collapse; he said the shipping industry needs systems to keep a ship on track when it loses power, as the Dali did before the collision.

The bridge itself, which carried more than 30,000 vehicles daily, appeared to be structurally sound. Its condition was rated fair, according to data in the 2023 National Bridge Inventory maintained by the Federal Highway Administration. Maryland state officials said they were focused on search-and-rescue operations and did not provide later inspection data. National Transportation Safety Board Chair Jennifer Homendy said excavating detailed inspection history information — and what was done in response to any earlier findings — will be a cumbersome and protracted part of the agency’s investigation.

But bridge safety and engineering experts are emphasizing a separate issue: protective barriers.

When the span opened to traffic in 1977, many ships were smaller and the standards for protecting bridges against them were lower, they said.

A few years later, a Liberian cargo ship crashed into a bridge in Florida , sending a Greyhound bus, a pickup truck and six cars into the Tampa Bay and killing 35 people, according to the NTSB. That deadly 1980 collision helped lead to the adoption of stronger national standards for bridges, including protection from errant ships, in the years that followed, safety experts said.

Sherif El-Tawil, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at University of Michigan with expertise in bridges, said if the Key Bridge had been built after those updated standards from the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials were put in place, the span could still be standing.

“I believe it would have survived,” El-Tawil said.

Maryland officials did not answer questions Tuesday about what protective devices were in place near the bridge and whether they were sufficient to withstand this type of collision.

Two examples of protective measures that did not appear to have been in place, El-Tawil said, were large fenders designed to direct marine traffic away from the bridge supports and an island built around the pier.

Some states are building these kinds of protection systems around vital bridges. Last year, officials from a joint New Jersey and Delaware bridge authority announced work on eight 80-foot-wide, stone-filled cylinders designed to protect the Delaware Memorial Bridge. The existing protection for the bridge tower piers dates to 1951. “Today’s tankers and ships are bigger and faster than those of the 1950s and 1960s,” the officials said in announcing the nearly $93 million project.

State departments of transportation “are aware of the shortcomings of these bridges,” said Roberto T. Leon, a bridge and structural engineering professor at Virginia Tech. “It’s not that they don’t know. It’s a matter of prioritizing the repairs. It is a very expensive proposition to protect a bridge.”

Ian Firth, a British structural engineer and bridge designer, said he was “not surprised” at how quickly the bridge came down after it was hit. He noted that the support structure that was struck, which would have been made of reinforced concrete, was one of two main supports responsible for doing “all the work” to hold up the bridge.

He said the ship appeared to have strayed to one side before striking the bridge.

The bridge collapse, like other calamities, is probably the result of overlapping low-probability failures, said Edward Tenner, a historian and expert on disasters — akin to what happens when, by chance, the holes in a stack of Swiss cheese slices line up perfectly.

“This might have been a case where there were just an unlikely series of failures,” said Tenner, author of “Why Things Bite Back,” a book about technology and its unanticipated consequences. But he added, “I suspect there was something about the equipment of a huge ship like that, given the potential for damage like this, there should have been more redundancy. There shouldn’t have been one point of failure that could lead to a catastrophe.”

Speaking Tuesday afternoon in Baltimore, U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg called the accident “a unique circumstance,” adding, “I do not know of a bridge that has been constructed to withstand a direct impact from a vessel of this size.”

The ship was towed into the Patapsco River initially, but the tugboats did not accompany the ship all the way to the bridge, said John Konrad, a retired ship captain who runs the gCaptain maritime news website and co-authored a book on the Deepwater Horizon oil spill .

“The safe thing to do is keep the tugs,” Konrad said. “Moving forward, I think that’s going to happen. The Coast Guard is going to say you’ve got to keep the tugs tied up until you pass the bridge.”

In video imagery, the ship can be seen losing electrical power, then briefly regaining it before going completely dark. The ship then veers to the right, directly toward the bridge’s structural support.

The rudder may have gotten stuck in a position that caused the ship to turn, said a senior retired maritime official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity while waiting for more details on the incident. It’s also possible that an incoming tide could have been a factor, he said.

“Obviously, they could not control the ship. They could not stop the ship,” he said.

A deficiency in the Dali’s systems was discovered when the ship was inspected in June, records show. Inspectors at the port of San Antonio, Chile, discovered a problem categorized as relating to “propulsion and auxiliary machinery,” according to the Tokyo MOU, an intergovernmental shipping regulator in the Asia-Pacific region. The issue was classified in the subcategory of “Gauges, thermometers, etc,” but no additional details of the deficiency were provided. The problem was not serious enough to warrant detaining the ship, according to the records.

After a follow-up inspection later the same day, the Dali was found to have no outstanding deficiencies, the records show, indicating that the problem was addressed.

Maryland Gov. Wes Moore (D) said at a news conference Tuesday that the Dali lost power and issued an emergency call for help shortly before the freighter crashed into the bridge. The “mayday” distress call allowed officials to halt vehicle traffic headed over the bridge and saved lives, Moore said.

Erin Cox, Tom Jackman, Jon Swaine, Joyce Lee and Mark Johnson contributed to this report.

An earlier version of this article misstated the title of Edward Tenner's book. It is "Why Things Bite Back." This version has been corrected.

Baltimore bridge collapse

How it happened: Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge collapsed after being hit by a cargo ship . The container ship lost power shortly before hitting the bridge, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore (D) said. Video shows the bridge collapse in under 40 seconds.

Victims: Divers have recovered the bodies of two construction workers , officials said. They were fathers, husbands and hard workers . A mayday call from the ship prompted first responders to shut down traffic on the four-lane bridge, saving lives.

Economic impact: The collapse of the bridge severed ocean links to the Port of Baltimore, which provides about 20,000 jobs to the area . See how the collapse will disrupt the supply of cars, coal and other goods .

Rebuilding: The bridge, built in the 1970s , will probably take years and cost hundreds of millions of dollars to rebuild , experts said.

Baltimore bridge collapse: What happened and what is the death toll?

What is the death toll, when did the baltimore bridge collapse, why did the bridge collapse, who will pay for the damage and how much will the bridge cost.

HOW LONG WILL IT TAKE TO REBUILD THE BRIDGE?

What ship hit the baltimore bridge, what do we know about the bridge that collapsed.

HOW WILL THE BRIDGE COLLAPSE IMPACT THE BALTIMORE PORT?

Get weekly news and analysis on the U.S. elections and how it matters to the world with the newsletter On the Campaign Trail. Sign up here.

Writing by Lisa Shumaker; Editing by Daniel Wallis and Bill Berkrot

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. , opens new tab

Thomson Reuters

Lisa's journalism career spans two decades, and she currently serves as the Americas Day Editor for the Global News Desk. She played a pivotal role in tracking the COVID pandemic and leading initiatives in speed, headline writing and multimedia. She has worked closely with the finance and company news teams on major stories, such as the departures of Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and significant developments at Apple, Alphabet, Facebook and Tesla. Her dedication and hard work have been recognized with the 2010 Desk Editor of the Year award and a Journalist of the Year nomination in 2020. Lisa is passionate about visual and long-form storytelling. She holds a degree in both psychology and journalism from Penn State University.

UK's Cameron calls for increased NATO spending amid Ukraine conflict

British Foreign Minister David Cameron on Wednesday called for NATO allies to bolster defense spending and production in support of Ukraine amid the ongoing Russian invasion.

Great choice! Your favorites are temporarily saved for this session. Sign in to save them permanently, access them on any device, and receive relevant alerts.

- Sailboat Guide

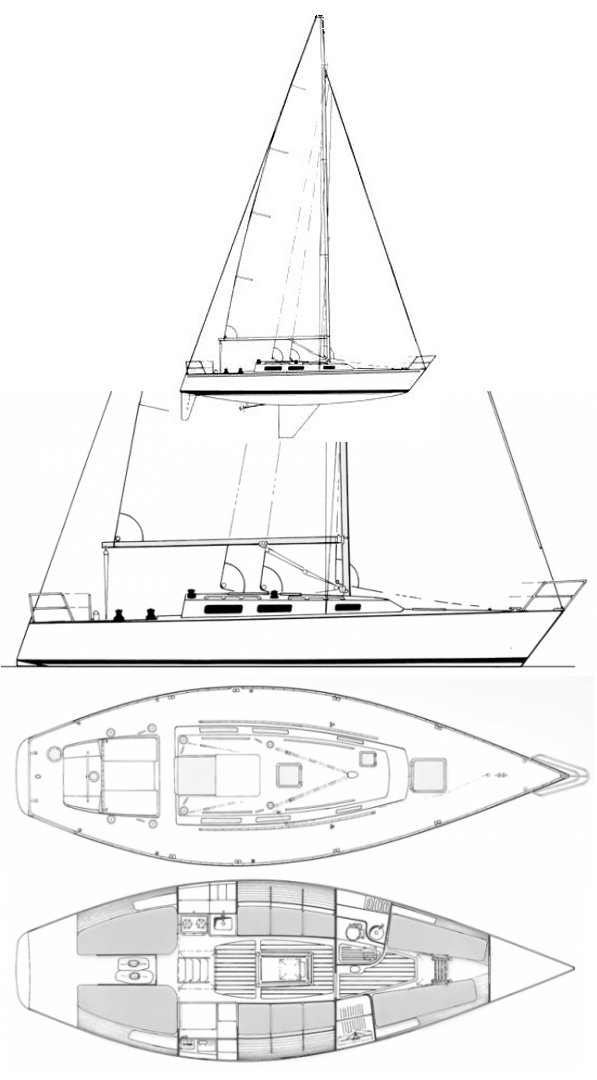

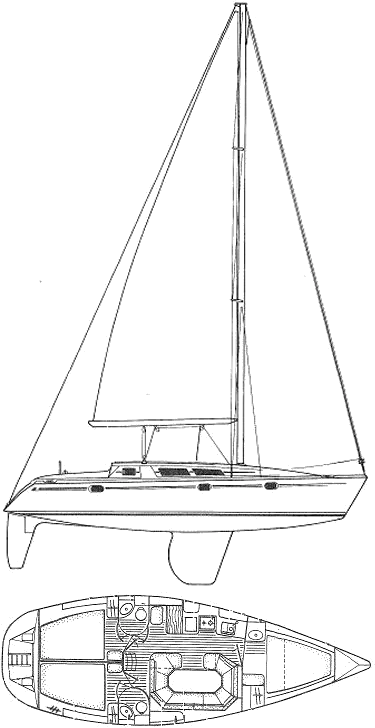

Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 36

Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 36 is a 36 ′ 1 ″ / 11 m monohull sailboat designed by J&J Design and Daniel Andrieu and built by Jeanneau between 1990 and 1992.

Rig and Sails

Auxilary power, accomodations, calculations.

The theoretical maximum speed that a displacement hull can move efficiently through the water is determined by it's waterline length and displacement. It may be unable to reach this speed if the boat is underpowered or heavily loaded, though it may exceed this speed given enough power. Read more.

Classic hull speed formula:

Hull Speed = 1.34 x √LWL

Max Speed/Length ratio = 8.26 ÷ Displacement/Length ratio .311 Hull Speed = Max Speed/Length ratio x √LWL

Sail Area / Displacement Ratio

A measure of the power of the sails relative to the weight of the boat. The higher the number, the higher the performance, but the harder the boat will be to handle. This ratio is a "non-dimensional" value that facilitates comparisons between boats of different types and sizes. Read more.

SA/D = SA ÷ (D ÷ 64) 2/3

- SA : Sail area in square feet, derived by adding the mainsail area to 100% of the foretriangle area (the lateral area above the deck between the mast and the forestay).

- D : Displacement in pounds.

Ballast / Displacement Ratio

A measure of the stability of a boat's hull that suggests how well a monohull will stand up to its sails. The ballast displacement ratio indicates how much of the weight of a boat is placed for maximum stability against capsizing and is an indicator of stiffness and resistance to capsize.

Ballast / Displacement * 100

Displacement / Length Ratio

A measure of the weight of the boat relative to it's length at the waterline. The higher a boat’s D/L ratio, the more easily it will carry a load and the more comfortable its motion will be. The lower a boat's ratio is, the less power it takes to drive the boat to its nominal hull speed or beyond. Read more.

D/L = (D ÷ 2240) ÷ (0.01 x LWL)³

- D: Displacement of the boat in pounds.

- LWL: Waterline length in feet

Comfort Ratio

This ratio assess how quickly and abruptly a boat’s hull reacts to waves in a significant seaway, these being the elements of a boat’s motion most likely to cause seasickness. Read more.

Comfort ratio = D ÷ (.65 x (.7 LWL + .3 LOA) x Beam 1.33 )

- D: Displacement of the boat in pounds

- LOA: Length overall in feet

- Beam: Width of boat at the widest point in feet

Capsize Screening Formula

This formula attempts to indicate whether a given boat might be too wide and light to readily right itself after being overturned in extreme conditions. Read more.

CSV = Beam ÷ ³√(D / 64)

Shallow draft model: 4.83’/1.47m. Originally called SUN DANCE 36.

Embed this page on your own website by copying and pasting this code.

- About Sailboat Guide

©2024 Sea Time Tech, LLC

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Six presumed dead after cargo ship crash levels Baltimore bridge

BALTIMORE — A major Baltimore bridge collapsed like a house of cards early Tuesday after it was struck by a container ship, sending six people to their deaths in the dark waters below, and closing one of the country’s busiest ports.

By nightfall, the desperate search for six people who were working on the bridge and vanished when it fell apart had become a grim search for bodies.

“We do not believe that we’re going to find any of these individuals still alive,” Coast Guard Rear Admiral Shannon N. Gilreath said.

Jeffrey Pritzker, executive vice president of Brawner Builders, said earlier that one of his workers had survived. He did not release their names.

Up until then, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore had held out hope that the missing people might be found even as law enforcement warned that the frigid water and the fact that there had been no sign of them since 1:30 a.m. when the ship struck Francis Scott Key Bridge.

Moore expressed heartbreak after officials suspended the search for survivors.

"Our heart goes out to the families," he said. "I can’t imagine how painful today has been for these families, how painful these hours have been have been for these families."

It was a crushing blow to the loved ones of the missing men, who had waited for hours at a Royal Farms convenience store near the entrance of the bridge for word of their fate.

Follow live updates on the Baltimore bridge collapse

The tragic chain of events began early Tuesday when the cargo ship Dali notified authorities that it had lost power and issued a mayday moments before the 984-foot vessel slammed into a bridge support at a speed of 8 knots, which is about 9 mph.

Moore declared a state of emergency while rescue crews using sonar detected at least five vehicles in the frigid 50-foot-deep water: three passenger cars, a cement truck and another vehicle of some kind. Authorities do not believe anyone was inside the vehicles.

Investigators quickly concluded that it was an accident and not an act of terrorism.

Ship was involved in another collision

Earlier, two people were rescued from the water, Baltimore Fire Chief James Wallace said. One was in good condition and refused treatment, he said. The other was seriously injured and was being treated in a trauma center.

Moore said other drivers might have been in the water had it not been for those who, upon hearing the mayday, blocked off the bridge and kept other vehicles from crossing.

“These people are heroes,” Moore said. “They saved lives.”

Nearly eight years ago, the Dali was involved in an accident. In July 2016, it struck a quay at the Port of Antwerp-Bruges in Belgium, damaging the quay.

The nautical commission investigated the accident, but the details of the inquiry were not immediately clear Tuesday.

The Dali is operated and managed by Synergy Group. In a statement, the company said that two port pilots were at the helm during Tuesday's crash and that all 22 crew members onboard were accounted for.

The Dali was chartered by the Danish shipping giant Maersk, which said it would have no choice but to send its ships to other nearby ports with the Port of Baltimore closed.

The bridge, which is about a mile and a half long and carries Interstate 695 over the Patapsco River southeast of Baltimore, was "fully up to code," Moore said.

National Transportation Safety Board Chairwoman Jennifer Homendy said that her agency will lead the investigation and that a data recorder on the ship could provide more information.

"But right now we're focusing on the people, on the families," she said. "The rest can wait."

President Joe Biden vowed to rebuild the bridge and send federal funds.

"This is going to take some time," the president warned. "The people of Baltimore can count on us though to stick with them, at every step of the way, till the port is reopened and the bridge is rebuilt."

Speaking in Baltimore, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg echoed the president's promise.

"This is no ordinary bridge," he said. "This is one of the cathedrals of American infrastructure."

But Buttigieg warned that replacing the bridge and reopening the port will take time and money and that it could affect supply chains.

The Port of Baltimore, the 11th largest in the U.S., is the busiest port for car imports and exports, handling more than 750,000 vehicles in 2023 alone, according to data from the Maryland Port Administration.

Writer David Simon, a champion of Baltimore who set his TV crime drama "The Wire" on the streets of the city he once covered as a reporter, warned online that the people who will suffer the most are those whose livelihoods depend on the port.

"Thinking first of the people on the bridge," Simon posted on X . "But the mind wanders to a port city strangling. All the people who rely on ships in and out."

Timeline of crash

Dramatic video captured the moment at 1:28 a.m. Tuesday when the Dali struck a support and sent the bridge tumbling into the water. A livestream showed cars and trucks on the bridge just before the strike. The ship did not sink, and its lights remained on.

Investigators said in a timeline that the Dali's lights suddenly shut off four minutes earlier before they came back on and that then, at 1:25 a.m. dark black smoke began billowing from the ship's chimney.

A minute later, at 1:26 a.m., the ship appeared to turn. And in the minutes before it slammed into the support, the lights flickered again.

Maryland Transportation Secretary Paul Wiedefeld said the workers on the bridge were repairing concrete ducts when the ship crashed into the structure.

At least seven workers were pouring concrete to fix potholes on the roadway on the bridge directly above where the ship hit, said James Krutzfeldt, a foreman.

Earlier, the Coast Guard said it had received a report that a “motor vessel made impact with the bridge” and confirmed it was the Dali, a containership sailing under a Singaporean flag that was heading for Sri Lanka.

Bobby Haines, who lives in Dundalk in Baltimore County, said he felt the impact of the bridge collapse from his house nearby.

"I woke up at 1:30 this morning and my house shook, and I was freaking out," he said. "I thought it was an earthquake, and to find out it was a bridge is really, really scary."

Families of bridge workers wait for updates

Earlier in the day, relatives of the construction crew waited for updates on their loved ones.

Marian Del Carmen Castellon told Telemundo her husband, Miguel Luna, 49, was working on the bridge.

“They only tell us that we have to wait and that they can’t give us information,” she said.

Castellon said she was "devastated, devastated because our heart is broken, because we don’t know how they have been rescued yet. We are just waiting for the news."

Luna's co-worker Jesús Campos said he felt crushed, too.

“It hurts my heart to see what is happening. We are human beings, and they are my folks,” he said.

Campos told The Baltimore Banner that the missing men are from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Mexico.

Active search and rescue ends

The Coast Guard said it was suspending the active search-and-rescue effort at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday.

"Coast Guard’s not going away, none of our partners are going away, but we’re just going to transition into a different phase," Gilreath said at a news conference.

Maryland State Police Superintendent Roland L. Butler, Jr., said it was moving to a recovery operation. Changing conditions have made it dangerous for divers, he said.

Butler pledged to "do our very best to recover those six missing people," but the conditions are difficult.

"If we look at how challenging it is at a simple motor vehicle crash to extract an individual, I'm sure we can all imagine how much harder it is to do it in inclement weather, when it's cold, under the water, with very limited to no visibility," he said.

"There's a tremendous amount of debris in the water," which can include sharp metal and other hazards, and that could take time, Butler said.

'A long road in front of us'

Built in 1977 and referred to locally as the Key Bridge, the structure was later named after the author of the American national anthem.

The bridge is more than 8,500 feet long, or 1.6 miles. Its main section spans 1,200 feet, and it was one of the longest continuous truss bridges in the world upon its completion, according to the National Steel Bridge Alliance .

About 31,000 vehicles a day use the bridge, which equals 11.3 million vehicles per year, according to the Maryland Transportation Authority.

The river and the Port of Baltimore are both key to the shipping industry on the East Coast, generating more than $3.3 billion a year and directly employing more than 15,000 people.

Asked what people in Baltimore can expect going forward, the state's transportation secretary said it is too early to tell.

"Obviously we reached out to a number of engineering companies, so obviously we have a long road in front of us," Wiedefeld said.

Julia Jester reported from Baltimore, Patrick Smith from London, Corky Siemaszko from New York and Phil Helsel from Los Angeles.

Julia Jester is a producer for NBC News based in Washington, D.C.

Patrick Smith is a London-based editor and reporter for NBC News Digital.

Phil Helsel is a reporter for NBC News.

Corky Siemaszko is a senior reporter for NBC News Digital.

Advertisement

The Dali was just starting a 27-day voyage.

The ship had spent two days in Baltimore’s port before setting off.

- Share full article

By Claire Moses and Jenny Gross

- Published March 26, 2024 Updated March 27, 2024

The Dali was less than 30 minutes into its planned 27-day journey when the ship ran into the Francis Scott Key Bridge on Tuesday.

The ship, which was sailing under the Singaporean flag, was on its way to Sri Lanka and was supposed to arrive there on April 22, according to VesselFinder, a ship tracking website.

The Dali, which is nearly 1,000 feet long, left the Baltimore port around 1 a.m. Eastern on Tuesday. The ship had two pilots onboard, according to a statement by its owners, Grace Ocean Investment. There were 22 crew members on board, the Maritime & Port Authority of Singapore said in a statement. There were no reports of any injuries, Grace Ocean said.

Before heading off on its voyage, the Dali had returned to the United States from Panama on March 19, harboring in New York. It then arrived on Saturday in Baltimore, where it spent two days in the port.

Maersk, the shipping giant, said in a statement on Tuesday that it had chartered the vessel, which was carrying Maersk cargo. No Maersk crew and personnel were onboard, the statement said, adding that the company was monitoring the investigations being carried out by the authorities and by Synergy Group, the company that was operating the vessel.

“We are horrified by what has happened in Baltimore, and our thoughts are with all of those affected,” the Maersk statement said.

The Dali was built in 2015 by the South Korea-based Hyundai Heavy Industries. The following year, the ship was involved in a minor incident when it hit a stone wall at the port of Antwerp . The Dali sustained damage at the time, but no one was injured.

Claire Moses is a reporter for the Express desk in London. More about Claire Moses

Jenny Gross is a reporter for The Times in London covering breaking news and other topics. More about Jenny Gross

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A boat with a BN of 1.6 or greater is a boat that will be reefed often in offshore cruising. Derek Harvey, "Multihulls for Cruising and Racing", International Marine, Camden, Maine, 1991, states that a BN of 1 is generally accepted as the dividing line between so-called slow and fast multihulls.

J/36 is a 35′ 11″ / 11 m monohull sailboat designed by Rod Johnstone and built by J Boats between 1981 and 1984. Great choice! Your favorites are temporarily saved for this session. ... A measure of the power of the sails relative to the weight of the boat. The higher the number, the higher the performance, but the harder the boat will be ...

J/36 Technical specifications & dimensions- including layouts, sailplan and hull profile.

The J36 is a 35.95ft fractional sloop designed by Johnstone and built in fiberglass by J Boats between 1981 and 1984. 55 units have been built. The J36 is a light sailboat which is a very high performer. It is very stable / stiff and has a low righting capability if capsized. It is best suited as a racing boat. The fuel capacity is originally ...

The Performance Racer-Cruiser the Family Can Enjoy. The J/36 was originally conceived and designed to compete without regards to any handicap rule that was popular in the 1970's and 1980's. It's primary goal was to have a fast, fun, enjoyable boat to sail that the family could enjoy. Since then the J/36 has enjoyed success racing under the PHRF ...

Immersion rate. The immersion rate is defined as the weight required to sink the boat a certain level. The immersion rate for J/36 is about 224 kg/cm, alternatively 1256 lbs/inch. Meaning: if you load 224 kg cargo on the boat then it will sink 1 cm. Alternatively, if you load 1256 lbs cargo on the boat it will sink 1 inch.

outer sunset. May 5, 2006. #9. sam_crocker said: J/36 was the predecessor of the 35. The 36 is heavier with a bigger rig. Here in the PNW the 35 rates 72, the 36 rates 79. The 36 was a tough boat to beat in Vic-Maui races, although that might have been a rating thing.

1 of 1. If you are a boat enthusiast looking to get more information on specs, built, make, etc. of different boats, then here is a complete review of J/36. Built by J Boats and designed by Rod Johnstone, the boat was first built in 1981. It has a hull type of Fin w/spade rudder and LOA is 10.96. Its sail area/displacement ratio 22.07.

1980 J Boats J36 / SL . This J sailboat has a hull made of fiberglass and has an overall length of 36 feet. The beam (or width) of this craft is 120 inches. This sailboat is rigged as a Sloop. The sail area for the boat is 635 square feet. Approximate displacement for the vessel comes in at around 10600 pounds.

A measure of the power of the sails relative to the weight of the boat. The higher the number, the higher the performance, but the harder the boat will be to handle. This ratio is a "non-dimensional" value that facilitates comparisons between boats of different types and sizes. Read more. Formula. SA/D = SA ÷ (D ÷ 64) 2/3

Keep in mind, the weight of a boat differs based on hull material, mast type, and many other factors. Dinghies (less than 12'): 100 to 200 pounds. Small Sailboats (15' to 20'): 400 to 2,500 pounds. Medium Sailboats (21' to 25'): 2,500 to 5,000 pounds. Cruising Sailboats (27' to 32'): 7,000 to 12,000 pounds.

There are presently 132 yachts for sale on YachtWorld for J Boats. This assortment encompasses 16 brand-new vessels and 116 pre-owned yachts, all of which are listed by knowledgeable boat and yacht brokers predominantly in United States, United Kingdom, France, Canada and Greece. The selection of models featured on YachtWorld spans a spectrum ...

Jan 7, 2007. #1. I am thinking of purchasing a "81 J36 with some water intrusion around the rudder post into the balsa core. I believe the area to be 3' in diameter max. The area compromised is above the waterline and I think I can cut out the inner liner, recore the affected areas and lay up the liner. Anyone have any experience with this or ...

44' Bruce Roberts Mauritius 43/44Honolulu, HawaiiAsking $68,899. 32' Westsail 32 Kendall. Puerto Vallarta. Asking $45,000. 24' Corsair Dash 750 MKII. Sadler Point Marina Jacksonville, Florida. Asking $66,200. 12' RS Sailing Feva XL.

Sailboat Rig Dimensions Database. Sailboat Rig Dimensions Database. Sail area calculations. Mainsail Area = P x E / 2. Headsail Area = (Luff x LP) / 2 (LP = shortest distance between clew and Luff) Genoa Area 150% = ( 1.5 x J x I ) / 2. Genoa Area 135% = ( 1.35 x J x I ) / 2.

914-506-5372. J Boats J/30. Savannah, Georgia. 1986. $19,000. Price Reduced $19000 After racing Ronin for the last 13 years in the Savannah/Hilton Head area, new adventures are ahead, and it is time for her to find a new home! She's fast, yet comfortable and has many more racing days ahead. She is currently moored at the Savannah Yacht Club ...

The weight required to sink the yacht one inch. Calculated by multiplying the LWL area by 5.333 for sea water or 5.2 for fresh water. ... 1997), states that a boat with a BN of less than 1.3 will be slow in light winds. A boat with a BN of 1.6 or greater is a boat that will be reefed often in offshore cruising. Derek Harvey, "Multihulls for ...

J 36 Sailboat for Sale, South Bristol, Maine. 106 likes · 1 talking about this. Outdoor & Sporting Goods Company

1981-J36, Quest, located in Squalicum Harbor, Bellingham, WA. Newer 3GM Yanmar water cooled motor, professional racing bottom and foils (2018), rigging, turn buckles and solid wire stays (2017), full length mainsail track (2017), Ray Marine Instruments (2021), masthead wand (2021), bilge pump (2022). ... Discover your dream boat. About Sailboat ...

Until 1 August 2020, there were three separate university boat clubs in Cambridge: one for open-weight men, one for lightweight men, and one for open-weight and lightweight women.

How it happened: Baltimore's Francis Scott Key Bridge collapsed after being hit by a cargo ship. The container ship lost power shortly before hitting the bridge, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore (D) said ...

After the bridge collapse in 2007 in Minnesota, Congress allocated $250 million. Initial estimates put the cost of rebuilding the bridge at $600 million, according to economic analysis company ...

The ballast displacement ratio indicates how much of the weight of a boat is placed for maximum stability against capsizing and is an indicator of stiffness and resistance to capsize. Formula. Ballast / Displacement * 100 43.53 <40: less stiff, less powerful >40: stiffer, more powerful.

March 28, 2024. The massive cargo ship that lost control and slammed into a major Baltimore bridge on Tuesday was not the first to do so. The same bridge was also hit by a wayward cargo vessel in ...

An aerial view shows the scene of a bridge collapse after a vessel struck the Francis Scott Key bridge in Baltimore on March 26.

Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 36 is a 36′ 1″ / 11 m monohull sailboat designed by J&J Design and Daniel Andrieu and built by Jeanneau between 1990 and 1992. Great choice! Your favorites are temporarily saved for this session. ... A measure of the power of the sails relative to the weight of the boat. The higher the number, the higher the performance ...

The capacity is measured in terms of TEUs, or 20-foot equivalent units, not containers. The ship that crashed into the bridge in Baltimore holds barely half of what some of the largest container ...

The weight required to sink the yacht one inch. Calculated by multiplying the LWL area by 5.333 for sea water or 5.2 for fresh water. ... 1997), states that a boat with a BN of less than 1.3 will be slow in light winds. A boat with a BN of 1.6 or greater is a boat that will be reefed often in offshore cruising. Derek Harvey, "Multihulls for ...

The Francis Scott Key bridge in Baltimore, Maryland, partially collapsed early Tuesday, police said. It was hit by a ship, officials said.

Published March 26, 2024 Updated March 27, 2024. The Dali was less than 30 minutes into its planned 27-day journey when the ship ran into the Francis Scott Key Bridge on Tuesday. The ship, which ...