- Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Donald Crowhurst: The fake round-the-world sailing story behind The Mercy

- October 2, 2019

The mysterious and tragic disappearance of the single-handed sailor Donald Crowhurst more than 50 years ago continues to fascinate. Nic Compton explains why...

Hailed as a round the world single-handed hero, Donald Crowhurst in fact never left the Atlantic during his 243 days at sea. Photo: Alamy

It was while I was researching my book about madness at sea in 2015 that I first heard a movie about Donald Crowhurst was in the works. Several websites published reports of a high-profile British feature starring Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz, and a few surreptitious photos of the cast filming off Teignmouth had been posted online. It seemed a lucky coincidence, given that my book would inevitably feature the Crowhurst story, but I assumed the movie would come out long before my book was ready.

Over the next couple of years, however, the release date for the film was repeatedly postponed – so much so that it became a running topic among Hollywood gossipmongers, who speculated that Crowhurst’s widow Clare had delayed progress, or that it was being held back to tie with the 50th anniversary of the events, or indeed that it might never be released in cinemas and go straight to DVD instead.

Meanwhile, I carried on writing my book, Off the Deep End , which was published in 2017, and the movie, The Mercy , was released in February 2018. There was never any doubt the tragic story of Donald Crowhurst would have to be included in any book about madness at sea.

Colin Firth stars as Donald Crowhurst in the 2018 film The Mercy . Photo: Studio Canal

Of all the stories I researched, it’s the one that has caught the public imagination most. Long before the latest Hollywood offering it inspired movies, books, plays, art installations, an epic poem and even an opera. Whereas many stories of adventures at sea seem to leave the general public cold, the Crowhurst tale continues to fascinate more than 50 years after Teignmouth’s most famous sailor vanished without trace. And yet, despite the thousands of words written about him, we really know very little more about him than we did 50 years ago.

It all started when Francis Chichester made his historic single-handed circumnavigation in 1966-67 – not the first to do so, by any means, but certainly the fastest up to that point, completing the loop in 226 days with just one stop, in Sydney, to repair his self-steering. Even before he’d docked at Plymouth there was a general realisation, which spread like osmosis throughout the sailing world, that the next step would be to sail around solo without stopping.

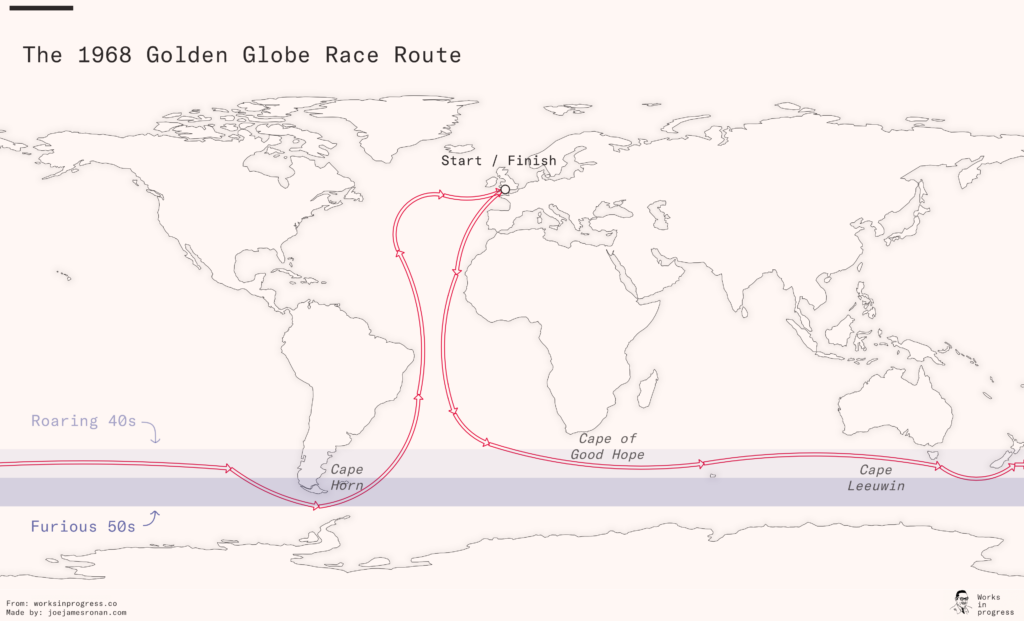

The challenge was turned into a contest by the Sunday Times which, in March 1968, announced two prizes: a Golden Globe trophy for the first person to sail round the world via the Three Capes single-handed and non-stop, and a £5,000 cash prize for the person to do it in the fastest time. The only stipulation was that competitors had to leave from a British port between 1 June and 31 October 1968, and had to return to the same place.

Article continues below…

A voyage for 21st Century madmen? What drives the Golden Globe skippers

A voyage for madmen, so was the original Sunday Times Golden Globe Race deemed. When the first non-stop race around…

How extreme barnacle growth hobbled the 2018-19 Golden Globe Race fleet

Eighty-knot gales, 10m-high waves, pitchpoling, loneliness and ever-depleting food reserves… of all the challenges facing a single-handed non-stop circumnavigator you…

Nine skippers eventually signed up for the race: the famous transatlantic rowing duo Chay Blyth and John Ridgway, who had by then fallen out but were sailing near-identical 30ft glassfibre production boats; Bernard Moitessier, already something of a legend in France for breaking the long-distance sailing record on his steel ketch Joshua; Moitessier’s friend Loïc Fougeron; Robin Knox-Johnston , an unknown British merchant navy officer sailing a heavy wooden boat called Suhaili ; two former British naval officers, Bill King and Nigel Tetley; the experienced Italian single-handed sailor Alex Carozzo; and Donald Crowhurst.

Out of the group, Crowhurst was by far the least experienced, the odd one out. Born in India in 1932, he went to Loughborough College after the war, until family nances and the death of his father forced him to cut his education short. He joined the RAF in 1948 but was chucked out after six years because of some high jinks with a vehicle; the same thing happened when he joined the army and he was forced to resign after he was caught trying to hotwire a car during a drunken escapade.

Persuasive character

Crowhurst with his wife Clare and their children Rachel, Simon, Roger and James, circa October 1968. Photo: Getty Images

Next he got as job as a travelling salesman for an electrics company, but was again dismissed after crashing the company car.

Ever-persuasive, he talked himself into a job as chief design engineer for an electronics company in Somerset, and in 1962 set up his own company, Electron Utilisation, to manufacture electronic devices for yachts.

The company got off to a good start, selling a simple but well-designed radio direction finder which Crowhurst dubbed the Navicator. Pye Radio invested £8,500 in the project, before getting cold feet and pulling out.

It quickly became clear that while Crowhurst was a charismatic personality and brilliant innovator he didn’t have the business acumen to run a successful company, and Electron Utilisation was soon in financial trouble.

Crowhurst managed to persuade local businessman Stanley Best to invest £1,000 to carry the company over what he assured him was a temporary lean period.

It must have been obvious to Crowhurst that he was heading for another failure. By now 35 years old, he could see the same pattern repeating itself, of high ambition thwarted by petty practicalities. Only, by now married to Clare with four children and living in a comfortable house outside Bridgwater in Somerset, the stakes were higher than ever.

His response to failure was to reinvent himself yet again. This time he would become a record-breaking sailor, a seafaring hero in the vein of Chichester: he would sail around the world single-handed – even though he had until then only dabbled in sailing, mainly on board a 20ft sloop called Pot of Gold . First, however, he needed a boat.

After failing to persuade the Cutty Sark Committee to lend him Gipsy Moth IV for the voyage, he decided a trimaran would be the ideal craft – despite having never sailed on one. To get the funding to build his dream boat he achieved perhaps the greatest coup of his life.

With Electron Utilisation going down the pan, his backer Stanley Best wanted his loan repaid, but Crowhurst managed to persuade him the best way to get his money back would be to fund the construction of the new boat.

A replica of the 41ft Teignmouth Electron used in the filming of The Mercy . Photo: WENN Ltd/Alamy

The crux of his argument was that he would use the trimaran as a test bed for his new inventions, and the publicity gained from entering the race would catapult the company to success. The sting in the tail was that the loan was guaranteed by Electron Utilisation, which meant that, if the venture failed, the company would go bankrupt.

To understand how he managed this turnaround you have to go back in time. Photos of Crowhurst make him look geekish and uncool to the modern eye. With his sticky-out ears, high forehead, curly hair, tie and V-neck jumper, he appears the epitome of the eccentric inventor.

But all the contemporary accounts describe him as a charismatic, vibrant personality, the sort of person who lights up a room when they walk in – as well as being extremely clever. In fact, his cleverness was his problem. He had the gift of the gab and, once persuaded of something, could talk anyone into believing him.

“This is important,” said his wife Clare. “Donald had this definite talent. He would say the most amazing things, but then no matter how crazy they seemed, he’d be clever and ingenious enough to make them come true. Always. This is a most important point about his character.”

Crowhurst’s widow, Clare, holds the last photograph taken of Donald with his family. Photo: Guy Newman / Alamy

Slow off the mark

So Crowhurst got the money for Teignmouth Electron , which was built by Cox Marine in Essex and fitted out by JL Eastwood in Norfolk. It’s a measure of how far behind he was that by the time the Cox yard started building the hulls towards the end of June, Ridgway, Blyth and Knox-Johnston had already set off on their round-the-world attempts. In the event, complications meant the launch date was delayed and even when Crowhurst finally set off on 31 October – just a few hours before the Sunday Times deadline expired – his boat was barely complete.

None of the clever inventions he had devised for the boat were connected, including the all-important buoyancy bag at the top of the mast, which was supposed to inflate if the trimaran capsized. His revolutionary ‘computer’, which was supposed to monitor the performance of the boat and set off various safety devices, was no more than a bunch of unconnected wires.

Worse still, he had had to borrow yet more money from Best to finish the boat, and had mortgaged his home to guarantee the loan. Crowhurst made a desultory figure scrambling about the deck of his trimaran as he set off on his great adventure – only to turn around within a few minutes to untangle his jib and staysail halyards, which were snagged at the top of the mast.

It was just the start of his troubles. After two days at sea, while still within sight of Cornwall, the screws started falling off his self-steering and, not having any spares on board, he had to cannibalise other parts of the machine to replace them.

A leaky boat

A few days later, halfway across the Bay of Biscay, he discovered the forward compartment of one of the hulls had filled up with water from a leaking hatch.

Soon, other compartments began to leak and, as he’d been unable to get the correct piping for the bilge pumps, his only option was to bail them out with a bucket. Then, two weeks after leaving Teignmouth, his generator broke down after being soaked with water from another leaking hatch.

“This bloody boat is just falling to pieces due to lack of attention to engineering detail!!!” he wrote in his log. A few days later he made a long list of jobs that needed doing and concluded his chances of survival if he carried on were at best 50/50. He began to think about abandoning the race.

But Crowhurst was in a triple bind. If he dropped out at this stage, not only would his reputation be destroyed but his business would go bankrupt and, perhaps worse of all, he and his family would lose their home. For all these reasons, giving up was not an option.

It soon became clear his estimates for the boat’s speed had been wildly optimistic: he had estimated an average of 220 miles per day, whereas the reality was about half that, on a good day. There was no way he was going to catch up with the other competitors or win either of the prizes, unless something extraordinary happened.

And so, just five weeks after setting off from Teignmouth, Crowhurst started one of the most audacious frauds in sailing history: he began falsifying his position. From 5 December, he created a fake log book, with accurately plotted sun sights, working back from imaginary positions.

To make it look convincing, he listened to forecasts for the relevant areas and wrote a fictional commentary as if he was experiencing those conditions. It was quite a feat of seamanship, and only someone of Crowhurst’s brilliance could have carried it off convincingly.

The great deception

After a few days’ practice he felt sufficiently confident to send his first ‘fake’ press release, claiming he’d sailed 243 miles in 24 hours, a new world record for a single-handed sailor. In fact, he’d actually sailed 160 miles, a personal best perhaps, but certainly no world record.

And so the great deception began. As Crowhurst slowly worked his way down the Atlantic, his imaginary avatar was already rounding the Cape of Good Hope and heading into the Indian Ocean. Gradually, partly through misunderstandings and partly due to the spin added by his agent back in the UK, Crowhurst’s positions became ever more exaggerated, until it looked like he might win the race after all.

Meanwhile, the real Crowhurst was pottering around the Atlantic – ‘hiding’ in exactly the same area he had, only a few weeks earlier, jokingly suggested a sailor might hide to falsify a round-the-world voyage. To make sure his radio signals weren’t picked up by the wrong land stations, he maintained radio silence for nearly three months, from the middle of January until the beginning of April, which he blamed on his generator breaking down again.

Teignmouth Electron was found drifting in mid-Atlantic, 700 miles west of the Azores, on 10 July 1969

Unbelievably, he even put ashore in a remote bay near Buenos Aires in Argentina to buy materials to repair one of the hulls, which had started to fall apart. Despite being greeted and logged by local officials, this rule-breaking stop remained undetected.

On 29 March he reached his most southerly point, hovering a few miles off the Falklands, 8,000 miles from home, before starting his ascent up the Atlantic.

Finally, on 9 April, he broke radio silence and exploded back into the race with a telegram containing the infamous line: “HEADING DIGGER RAMREZ” – suggesting he was approaching Diego Ramirez, a small island southwest of Cape Horn (in reality, he was just off Buenos Aires).

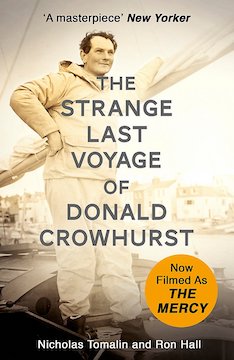

By this time Moitessier had had his ‘moment of madness’ and had dropped out of the race and was sailing to Tahiti ‘to save his soul’. The only other competitors left were Knox-Johnston, who was plodding slowly up the Atlantic and on track to be the first one home, and Tetley, racing in his wake to pick up the prize for the fastest voyage.

Rachel Weisz plays Clare Crowhurst in The Mercy

It seems likely that Crowhurst was planning to finish a close second to Tetley, which would save him from financial ruin without drawing too much attention to his fraudulent log books.

But his reappearance in the race had a dramatic effect on the course of events. Already nursing a broken boat up the homeward leg of the Atlantic, Tetley worried he might lose the speed record to the resurgent Crowhurst, and started pushing his trimaran faster towards the finish line. Some 1,100 miles from home, the inevitable happened: Tetley’s boat broke up and sank, and he had to be rescued by a passing ship.

Suddenly, the spotlight shifted to Crowhurst, the unlikely amateur who’d apparently come out of nowhere to beat the professionals. The BBC had a crew on standby to record his homecoming and hundreds of thousands of people were expected to throng the seafront at Teignmouth to welcome him home.

It was everything Crowhurst dreaded. As one of the winners, his books would come under much closer scrutiny – and indeed there were already some, including race chairman Francis Chichester, who suspected something wasn’t quite right.

In the middle of June, Crowhurst reached the Sargasso Sea and, as the tradewinds died and his boat slowed down, he descended into a mental quagmire of his own. It was as if all his previous failures had caught up with him in this one grand, final failure.

Teignmouth Electron on Cayman Brac in 1991. The wreck has deteriorated considerably since. Photo: Geophotos / Alamy

And this time there was no way out, no way of reinventing himself. Instead, he gave up ‘sailorising’ and resorted to philosophising instead. Over the course of a week, he wrote a 25,000-word manifesto that described how mankind had achieved such an advanced evolutionary state that it could now merge with the cosmos. All that was needed was ‘an effort of free will’.

He ended his journal on 1 July with this desperate appeal: ‘I will only resign this game / if you agree that / the next occasion that this / game is played / it will be played / according to the / rules that are devised by / my great god who has / revealed at last to his son / not only the exact nature / of the reason for games but / has also revealed the truth of / the way of the ending of the / next game that / It is finished / It is finished / IT IS THE MERCY’

There then followed a countdown, ending at 11:20:40 precisely. It’s not known what happened next, but it’s generally assumed Crowhurst jumped over the side of the boat to his death. His empty yacht was found by a passing ship on 10 July with two sets of log books on board: the real and the fake.

It was left to Sunday Times journalists Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall to piece together what had happened and to reveal to the world Crowhurst’s elaborate hoax. With Crowhurst and Tetley both out of the race, Knox-Johnston, on his slow wooden tortoise of a boat, was the only person to finish the race and was duly award both prizes – though he subsequently donated the £5,000 cash prize to Crowhurst’s widow.

Huge public interest

The Golden Globe race generated enormous public interest at the time, and the discovery of Crowhurst’s boat was front page news. It’s a fascination that has continued almost unabated to this day. The French film Les Quarantièmes Rugissants , based on the Crowhurst story, was released in 1982, while at least five plays have picked up the theme, as well as the 1998 opera Ravenshead.

In 2006, the acclaimed documentary Deep Water incorporated contemporary footage of the race, including some shot by Crowhurst during his voyage, and in 2017 director Simon Rumley released his own stylised take on the story, called simply Crowhurst.

The Mercy , then, is only the latest take on the Crowhurst saga – although with Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz on board, it is the most high-profile. So how does it compare to previous efforts?

As you’d expect of such a mainstream movie, the focus is firmly on the psychological drama rather than on the sailing – which is probably just as well considering how often films get the details of sailing wrong. There are some minor errors – Chichester wasn’t the first person to sail around the world single-handed, and the prize for the first competitor to finish the race was a trophy, not £5,000 – but the sailing scenes are generally quite convincing.

More importantly though, The Mercy is a captivating psychological drama, which shows how, through a series of small steps, a person can box themselves into a corner from which there is no escape. It’s this humbling of a deluded but essentially well-meaning man that gives the story such resonance and has inspired artists and writers for more than five decades. For, as anyone who has sailed out of sight of land knows, the sea has a knack of bringing out our inner demons. There is a Crowhurst in us all.

First published in the March 2018 edition of Yachting World. The Mercy is available to watch on BBC iPlayer until 11 Jan 2021 .

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright and DMCA Notice

Donald Crowhurst and his Fatal Race Round the World

In 1968, British newspaper The Sunday Times sponsored the first ever round-the-world yacht race. Guaranteed excellent publicity from the paper, nine contestants enlisted, drawn by the glamor of winning such a race, as well as the £5,000 prize for the fastest time (as much as $120,000 today).

The race was well organized but there were several safety concerns. Yachts were to be manned by a single person only as the race was a solo one, and the race would be non-stop. Competitors could not be vetted thoroughly on the safety of their boats and their abilities as sailors , and there were no entry requirements.

Competitors could start the race at any point between 1 June and 31 October 1968. One such competitor, who set off on the very last day, was Donald Crowhurst.

An Ambitious Man

Donald Crowhurst was not a professional sailor but had some knowledge and experience about sailing. He was an inventor and electronics engineer, and hoped to use this to his advantage during the race.

To aid in his navigation, he created a radio-direction finder that he named “Navicator” and he would make the attempt in a very unusual boat design, a trimaran called the Teignmouth Electron . Trimarans could theoretically travel much faster than monohull boats, but had not been tested on such a grueling expedition.

Crowhurst hoped to stabilize his business with the publicity and money that he would get by winning this race, but the upfront costs were steep. To take part, he raised financing from some businessmen and mortgaged his home as well.

This allowed him to finish work on the Teignmouth Electron which he had constructed specially for the voyage. The boat-builder promised Crowhurst that the boat would be speedy but warned about stability issues in heavy seas.

But on the first sea trial of the boat, a few noticeable problems came up. The deadline was rapidly approaching and it wasn’t possible for Crowhurst to equip new parts and repair the vessel properly to make it ready for the race.

- The Sarah Joe Mystery: Disappearance in the Pacific

- SS Baychimo: Ghost Ship of the Arctic

He only had two ways and was faced with a dire choice: either sail and take part in the race with a doubtful boat, or give up to face bankruptcy and humiliation. Crowhurst, fatefully, took the first option, setting sail in a boat untested in either design or practice.

The Race Begins!

Just like the boat wasn’t ready, the weather wasn’t favorable for the race as well. Clare, Crowhurst’s wife, suggested to him not to take part in it, as there was a great risk. But as she saw Crowhurst sobbing with the thought of humiliation, she and their four kids tried to make Crowhurst believe he could do anything. They didn’t want him to regret the thought of giving up.

On 31st October 1968, the weather miraculously calmed and gave Crowhurst his opportunity to start the voyage. Crowhurst kissed the forehead of each of his children and asked the elder ones to take care of their mother, and launched the Teignmouth Electron .

Soon after the race began, Crowhurst observed that the boat was already leaking like a sieve. And he realized right at that moment that this boat wouldn’t be able to take the blow from 30 or 40-foot (9 – 12 m) waves in the Southern Ocean , writing in the logs that the ship would probably sink once it entered heavy seas.

Trapped and with no options left, Crowhurst started to come up with a plan! He didn’t want to give up and live with humiliation forever, he would rather cheat than lose.

The Crooked Plan of Donald Crowhurst

GPS didn’t exist back then, and so the only way of checking the position of the boats after the race was through a review of the logbooks and the charts carried on each boat. Donald Crowhurst intended to use this to his advantage, saving his boat and completing the race.

Therefore, he started sending radio messages to the organizers giving false positions. He charted a false course down into the south Atlantic, and then, fearing his transmissions might give him away, he then disconnected the radio contact completely off the coast of Brazil .

Even these waters were too much for the T eignmouth Electron . His boat was so damaged at one point that he had to stop at a fishing port in Argentina to make some necessary repairs.

Crowhurst’s plan was to maintain two logbooks, one for his real journey and one for his fictitious race experience. The pressure of keeping two logbooks would have been extreme, and was made worse when he realized that his fictitious log wouldn’t be justifiable at close scrutiny if he won the race.

- Taken by the Ice: What Became of the Franklin Expedition Crew?

- Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight – Mystery at Sea

The logbooks would need to contain weather conditions during the course of his voyage. Crowhurst had no idea what the weather was like where he was supposed to be, and the fictitious log reflects some of this in its hazy descriptions.

Claiming to be making good time, Crowhurst wandered in the Atlantic until, finally, his made-up voyage started to catch up to his actual position. At this point the race leader was Nigel Tetley, who was making excellent time. Crowhurst intended to let Tetley win, with himself coming second to avoid much of the log-book scrutiny.

In May 1969, Donald finally turned back for home. But again he had miscalculated, as his apparent pace panicked Tetley. Forced to race at breakneck speed to keep up with Crowhurst’s apparent pace, Tetley’s boat failed and he capsized .

This meant Crowhurst was now far in the lead and on course to get the £5,000 prize for being the fastest competitor. With this victory he felt sure his cheating would be exposed.

After 243 days at sea, Crowhurst made his last entry in his logbook on 1st July 1969. He wrote, “It is finished, It is finished. It is the mercy.” And that was the last anyone heard of Donald Crowhurst.

Lost at Sea

12 days after his last logbook entry, the Teignmouth Electron was found drifting in the ocean . There was no sign of Donald Crowhurst. It was believed that he had jumped off the boat with his fictitious logbook, leaving behind the actual one on the deck by way of confessing his sins.

Crowhurst’s wife maintained that he would never commit suicide, but the evidence of the logbook was telling. He had hoped to become a British folk hero who conquered the seas, but in the end his sin was that of pride.

And so his life ended, trapped by his lies. Here was a man who believed he could sail across the world but couldn’t even make it past the Atlantic, and who believed he could fool the world, but ultimately left nothing behind but his confessional logbook.

Top Image: Donald Crowhurst never made it home. Source: hikolaj2 / Adobe Stock.

By Bipin Dimri

They Went To Sea In A Sieve, They Did. Available at: https://www.sportsnet.ca/more/big-read-donald-crowhursts-heartbreaking-round-world-hoax/

The Mysterious Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. Available at: https://howtheyplay.com/misc/The-Mysterious-Voyage-of-Donald-Crowhurst

The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. Available at: https://jollycontrarian.com/index.php?title=The_Strange_Last_Voyage_of_Donald_Crowhurst

Bipin Dimri

Bipin Dimri is a writer from India with an educational background in Management Studies. He has written for 8 years in a variety of fields including history, health and politics. Read More

Related Posts

Little rosalia lombardo and the mystery of the..., the book of soyga, the lives of shanti devi: proof of reincarnation, kitum cave: the deadliest place on earth, doveland, wisconsin: the town that wasn’t there, alfred loewenstein: how could the world’s third richest....

Stay up to date with notifications from The Independent

Notifications can be managed in browser preferences.

UK Edition Change

- UK Politics

- News Videos

- Paris 2024 Olympics

- Rugby Union

- Sport Videos

- John Rentoul

- Mary Dejevsky

- Andrew Grice

- Sean O’Grady

- Photography

- Theatre & Dance

- Culture Videos

- Fitness & Wellbeing

- Food & Drink

- Health & Families

- Royal Family

- Electric Vehicles

- Car Insurance Deals

- Lifestyle Videos

- Hotel Reviews

- News & Advice

- Simon Calder

- Australia & New Zealand

- South America

- C. America & Caribbean

- Middle East

- Politics Explained

- News Analysis

- Today’s Edition

- Home & Garden

- Broadband deals

- Fashion & Beauty

- Travel & Outdoors

- Sports & Fitness

- Climate 100

- Sustainable Living

- Climate Videos

- Solar Panels

- Behind The Headlines

- On The Ground

- Decomplicated

- You Ask The Questions

- Binge Watch

- Travel Smart

- Watch on your TV

- Crosswords & Puzzles

- Most Commented

- Newsletters

- Ask Me Anything

- Virtual Events

- Wine Offers

- Betting Sites

Thank you for registering

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in

Drama on the waves: The Life And Death of Donald Crowhurst

In 1968 an amateur sailor set off on the inaugural solo round-the-world yacht race. incredibly, he appeared to be leading the race until the closing stages when he disappeared and was never seen again. now the tragic truth about this very british hoaxer is being told. ed caesar reports, article bookmarked.

Find your bookmarks in your Independent Premium section, under my profile

For free real time breaking news alerts sent straight to your inbox sign up to our breaking news emails

Sign up to our free breaking news emails, thanks for signing up to the breaking news email.

For the past week, Britain has been in the thrall of an extraordinary sporting challenge. Within 24 hours of the start of the Velux 5 Oceans, a three-stage solo round-the-world yacht race starting in Bilbao, four sailors were forced to return to port, so horrific were the conditions off the coast of Spain. It was a reminder, if one were needed, that a solo circumnavigation of the globe remains the Everest of sporting achievements. Sir Robin Knox-Johnston - who, at 67, is the Velux 5 Oceans' oldest competitor - called the Bay of Biscay's 40ft waves and high winds "boat-breaking".

He should know. In 1969, without the global positioning systems, or support crews, or the corporate sponsorship with which modern single-handers put to sea, Knox-Johnston became the first person to complete a non-stop solo circumnavigation on his boat Suhaili, winning the inaugural Sunday Times Golden Globe Race in the process. "In 1969, my only advance weather system," said Knox-Johnston last week, "was a barometer from the wall of a pub".

But as remarkable as Knox-Johnston's feat was, it will forever be eclipsed by the plight of one of his fellow competitors in that first race: Donald Crowhurst, a 36-year-old English businessman, who went to sea in a leaky boat and committed suicide in the Atlantic 243 days later. Now, splicing harrowing onboard audio and visual footage of Crowhurst with interviews of the sailor's friends and family, a film, Deep Water, tells the story of Crowhurst's last voyage, and his descent into madness.

A former RAF pilot with a small, ailing electronics business called Electron Utilisation, Crowhurst was, at best, an enthusiastic weekend sailor. He was also married and a father of four children. So what convinced him he should go to sea for nine months is anyone's guess. But not only was Crowhurst determined to enter the race, he was determined to win.

To understand Crowhurst's peculiar obsession with competing in this gruelling race, one needs to know that in 1968, Britain was in the grip of sailing fever. The previous year, Sir Francis Chichester had achieved the then monumental feat of sailing around the world, on his own, punctuated only by a stop in Australia. In the era of the space race, when the possibilities of human endeavour seemed limitless, the world lapped up the heroism of Chichester's achievement, and 250,000 people lined the south coast to cheer him home.

The Sunday Times, which had reaped the rewards of sponsoring Chichester's journey, was looking for a way to continue tapping into the appetite for maritime derring-do. The Sunday Times Golden Globe Race was born. Using the clipper route, from Britain, through the Atlantic and round the Cape of Good Hope; through the Indian and Pacific Oceans; round Cape Horn and back to Britain, the competition was billed as a test for the world's greatest yachtsmen.

But, to encourage entrants, no evidence of sailing experience was required, and competitors were allowed to set off any time before 31 October. A trophy for the first man to complete the course, and a separate prize of £5,000 for the fastest time, would be awarded. Out of the nine men who set off in 1968, only one, Knox-Johnston, finished.

Crowhurst's bid to win the Golden Globe always looked precarious. In the months before the race, the businessman had become convinced that by coupling a new, triple-hulled boat design with his own technological innovations (a self-righting mechanism in case of capsize, for instance), he could win. With the financial support of a local businessman, Stanley Best, Crowhurst bought and developed his vessel. But Best's money came with a proviso: if Crowhurst failed to finish the race, he would have to pay for the boat himself.

To make matters more complicated for Crowhurst, he fell into the hands of one of Fleet Street's more manipulative press officers, Rodney Hallworth, who knew Crowhurst was journalistic manna. Hallworth sold him to the press as a plucky, English amateur with incredible prospects of bringing home the big prize. All the while, the deadline for starting the race, 31 October, was creeping round, and Crowhurst was struggling to make his boat, the Teignmouth Electron, seaworthy.

The day before his voyage began, Crowhurst made last-minute preparations on the Electron, then retired to a hotel with his wife, Clare. That night, he broke down in tears. The boat, he knew, was not ready. But he also knew it was too late to pull out. Hallworth would not allow it. Best would want his money back. The family would be ruined.

Crowhurst set sail the next day with unsorted provisions and vital equipment strewn across the deck of the Electron. And, even at this early stage, calamity loomed. He was forced to return to harbour in the first minutes of his journey when an anti-capsize air-bag got caught in the rigging.

Over the next two weeks, Crowhurst made slow progress. As Knox-Johnston and the Frenchman, Bernard Moitessier, who had set off weeks earlier, neared New Zealand, Crowhurst was languishing in the North Atlantic. At least he was afloat. Four men - John Ridgway, Loick Fougeron, Bill King and Alex Carozzo - retired before they reached the Indian Ocean. Of the four who remained, one Englishman, Chay Blyth, who set off with no sailing experience, retired in East London, South Africa. Another, Nigel Tetley, was making good time ahead of Crowhurst.

But if Crowhurst's slow times were worrying, they were as nothing compared to the anxiety he felt about the state of his boat. The Electron had started to leak, and her skipper faced a dilemma. Should he continue into the Southern Ocean, where his boat would almost certainly sink? Or should he return home to face shame and financial ruin?

In the end, Crowhurst did neither. Instead, he started to radio a series of incredible positions and speeds to Hallworth, who, in turn, embellished the lies and sold them to Fleet Street as fact. Suddenly, Crowhurst seemed to have a genuine chance of scooping the prize for the fastest circumnavigation.

The truth was that the difference between Crowhurst's real and stated positions was growing by the day, a discrepancy he kept track of by recording two logbooks. But this ruse only exacerbated his problems. Because of the frailty of the Electron, Crowhurst could not enter the perilous Southern Ocean. Neither could he return home, where ignominy and bankruptcy awaited. All the while, his wife, his four young children, and the rest of the world thought he was sailing into the record books.

Faced with an insoluble problem, Crowhurst did the only thing he could think of; he stayed put. Bobbing around in the Atlantic off Brazil, Crowhurst scrupulously filled out his fraudulent logbook, and cut off all radio contact with the world for three months. At one point, he was forced to pull into an Argentine fishing port to make vital repairs to his boat, an action that in itself would have been enough to disqualify him from the race. Still, Crowhurst kept up his pretence.

His fellow competitor, Moitessier, disillusioned about competing in a commercially motivated event, had rejected the idea of finishing the race at all. Instead, he simply to kept on sailing, eventually dropping anchor in Tahiti, after one and a half laps of the globe. Knox-Johnston arrived back in England to a hero's welcome. He had won the trophy for coming in first. But he had made slow time, a leisurely 312 days. In the eyes of the world, the race was now on between Tetley and Crowhurst to see which man would win the race for the £5,000.

The thought of winning terrified Crowhurst. He knew that if he came home in the fastest time, his logbook would be subject to scrupulous checks by the Golden Globe judges and the press. He determined on making a slow journey across the Atlantic, so Tetley would win the prize, and he could come in a dignified, unheroic second. Re-establishing radio contact with Hallworth for the first time in 12 weeks, Crowhurst confirmed he would not be able to catch Tetley. Still, his family and friends, who had been fearing the worst for Crow-hurst, were relieved that he was, apparently, safe and well.

Crowhurst's scheme was looking good. In May 1969, he began to make for home, his faked journey matching his real one for the first time in months. Then, disaster. Tetley, thinking Crowhurst was hot on his heels, had pushed his boat too hard, and sunk in the Azores. Crowhurst was going to win the prize.

The news of Tetley's sinking affected Crowhurst profoundly. He drifted deep into depression, refusing to sail, and took to his logbook. As he lolled in the mid-Atlantic, Crowhurst wrote a 25,000-word treatise on time travel and divinity. He counted down his remaining hours on Earth, believing death would not only be "the mercy" but that it would transform him into a "cosmic being". On 29 June 1969, after 243 days at sea, Crowhurst made one last entry into his logbook. His self-allotted time had come. This was "the mercy" he had been praying for. His boat was found 12 days later, with logbooks recording his genuine position and grainy sound and video recordings unharmed. It has since been assumed Crowhurst took the logbook of his fraudulent positions with him as he threw himself overboard. Back in Britain, Knox-Johnston was awarded the £5,000 for the fastest time, which he donated to the Crowhurst family, and Tetley was given a consolation prize. For unknown reasons, Tetley committed suicide a year later.

Deep Water's co-producer, Al Morrow, said: "What I felt about Donald was that although not all of us would go to sea, the situation was one that any of us could have got ourselves into. You tell one tiny little lie, and that turns into another lie, and suddenly there's no way out. The other thing that really struck me about the story is that being on your own for nine months at sea is such a unique thing. You have no one to speak to. He must have been so lonely."

Her fellow producer, Jonny Persey, added: "I recognise [Crowhurst's story] could arouse feelings of anger. He could have done the right thing any number of times. He had those opportunities, but every decision he made was wrong. It was very hard for his family to contribute to this film, but they have come to a point where they understand what happened, and recognise the complexity of what was going on with Donald."

The first screening of Deep Water, with the creative team and the family, was a charged occasion, says Morrow. "I was terrified," she admits. "The family had been so supportive through the process, but they had to trust us with the direction the film was going in. Clare's daughter, Rachel, walked out a few times in the screening, because she found it too emotional to sit through."

Another person in whom Deep Water will strike a resonating chord is Knox-Johnston, himself an interviewee for the film. Unable to attend any preview screenings, he has taken a DVD of Deep Water on his Velux 5 Oceans boat, Saga Insurance. When he finds a spare two hours away from racing, he will watch Crowhurst's story, all alone at sea.

Deep Water is released on 15 December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

New to The Independent?

Or if you would prefer:

Hi {{indy.fullName}}

- My Independent Premium

- Account details

- Help centre

The Maintenance Race

The world’s first round-the-world solo yacht race was a thrilling and, for some, deadly contest. Its contestants’ efforts can teach us about the art of maintenance.

The story is a draft, an invitation to readers to comment while the text and illustrations are still malleable, open to improvement. In the terminology of the racers in this story, it’s a shakedown cruise, a sea trial – a time to find the things that need fixing while they’re still easy to fix. You can help me with the piece by commenting on the piece on Books in Progress , where my new book, Maintenance is appearing online . I’ll be announcing some of the changes I make and recognizing helpful commenters on my Twitter.

Stewart Brand

P robably a great many famous stories could be retold in terms of maintenance.

Here’s one – the Golden Globe around-the-world solo sailboat race of 1968. Its drama continues to echo half a century later because three of the nine competitors became legendary – the one who won, the one who didn’t bother to win, and the one who cheated.

Their stories are usually told as a contest of wills and endurance, but at heart, it was a contest of maintenance styles.

The setup was this. In early 1968, editors and journalists at the Sunday Times in London noticed that several sailors were finding sponsors for their attempts at a new world record: to make the first solo voyage by sailboat around the world without stopping. The editors decided to co-opt the whole thing by declaring it a race. On March 17 they announced:

“ The £5,000 Sunday Times round-the-world race prize will be awarded to the single-handed yachtsman who completes the fastest non-stop circumnavigation of the world departing after June I and before October 31, 1968 . . . The Sunday Times Golden Globe will be awarded to the first non-stop single-handed circumnavigator of the world . . . The circumnavigation must be completed without outside physical assistance, and no fuel, food, water, or equipment may be taken aboard after the start. Those are the only conditions . . . “

There were two awards – one a cash prize, the other a trophy – because the sailors were planning to leave at different times, and one might be the first to complete the trip while another who left later might turn out to be the fastest. They were racing each other and the clock.

For the 30,000-mile circumnavigation, all the racers would sail from England down the Atlantic to the perilous Southern Ocean – the ‘Roaring Forties’ latitudes between 40 and 50 degrees south of the equator – where storms and waves that are sometimes immense blast eternally from the west, uninterrupted all the way around the world. With that wind behind them, the racers would head east below Africa, then Australia, then South America, and then – if they got that far – north back to England.

The racers were required to depart between June and October in order to arrive at the Southern Ocean between November and February, when the southern hemisphere summer makes the sailing a little less hazardous.

It was expected that even the fastest competitor would take ten months to get home. Some psychiatrists predicted that so many months totally alone, at times in extreme danger, might drive them mad.

Few modern ships use the far Southern Ocean. A boat in trouble could not count on help from anyone. GPS and electronic autopilots didn’t exist in 1968, radio was primitive, and radar didn’t fit on small boats. The mariners would navigate like their ancestors, solely by sextant, almanac, chronometer, and nautical chart. Without broadcast weather information, each sailor would have to make their own forecasts based on their barometer and what they could see of cloud, wind, and swell conditions. To free them from steering so they could sleep, cook, and do maintenance, they each relied on a complex self-steering device that kept the boat on a steady course in relation to the direction of the wind.

Every piece of equipment on board, and the structure of the boat itself, would be stressed for months on end. Since going ashore for repairs was forbidden, maintenance would have to be ceaseless and done at sea. Failure of a critical element at a critical time could mean death.

But the £5,000 award for the fastest trip was a serious incentive. These days it would be worth about $100,000. Fame, for the winners, would be worth far more.

The youngest of the three competitors who became legendary was Robin Knox-Johnston. Though only 29 years old, he could draw on invaluable experience. With some friends, he had sailed his 32-foot wood ketch SUHAILI 17,000 miles from India to England, gaining crucial knowledge of the boat’s seaworthiness and its match to his skills. In his account of the Golden Globe Race, A World of My Own , he wrote:

“ Perhaps her greatest advantage . . . is that she is not complicated and there were very few maintenance tasks I could not carry out myself. The wear and tear and battering to be expected during a 300-day voyage meant that constant maintenance was essential, but this came easily to someone who had served an apprenticeship in the Merchant Navy. [A bosun named Bertie Miller] taught us our knots and splices, canvas work, rigging, how to work a paintbrush properly, and the thousand-and-one finer practical points that make the difference between the seaman and a hand. It was Bertie who gave us a respect for the materials and the tools we used and took tremendous trouble to see that we set about a job the right way and finished it off properly.”

Knox-Johnston had tried to build a boat specifically designed for sailing around the world, but he couldn’t raise the money for it. Stuck with the wood 32-footer he had, he decided his governing principle would be ‘Make do and mend’.

To prepare SUHAILI for a ten-month passage, most of it in the world’s roughest waters, he packed into his small boat all the ‘materials and tools’ he could imagine he might need – specialized wrenches for every exotic nut on the boat; ditto for screwdrivers; a sailmaker’s bag full of needles, sewing palms, and twine; a bosun’s bag with every kind of shackle, thimble, and marlinspike for managing all his steel wire rope; a spare bilge pump and extra rubber pipe; 12 yards of canvas; caulking chisels and cotton; plenty of oil, glue, and Stockholm tar; spare parts for everything mechanical; and medical supplies for repairing himself.

Knox-Johnston’s daring habit when the wind was light was to dive off his bow and swim alongside the boat for a while. Then he would grab a line trailing off the stern and climb aboard refreshed. His comfort in the water turned out to be crucial for dealing with his first crisis.

A month after departure from England, it became clear that SUHAILI had a very serious leak, forcing him to pump the bilges twice a day. On a calm day off the coast of West Africa, he went over the side with mask and snorkel and discovered two long gaps in the planking on each side of the keel, and they moved with the rolling of the boat. Over a cigarette, he considered the nature of the problem and what he might be able to do about it. (Skilled maintainers advise never trying to solve a new or complex problem without a thorough mulling first.) If it was a structural issue, it could cause the boat to eventually break apart, but she had been overbuilt of strong India teak, and maybe it was just a matter of caulking the gaps – if he could figure out how to do it all by himself at sea.

Dressing in a dark shirt and jeans to hide his white body from potential sharks, he dove down and tried wedging strips of cotton caulking into the gaps. But five feet underwater, he couldn’t hold his breath long enough to secure the caulking in place.

He thought some more. Then he cut a 1- 1/2inch canvas strip seven feet long, sewed caulking to one side of it, coated it with Stockholm tar, and pushed tacks through the canvas every six inches. With a hammer he kept suspended below the hull, he was able to pound in the tacks to hold the caulking in place, but he could only manage one tack at a time before having to surface to breathe. It took two hours.

Then, worried that the canvas strip might tear off eventually, he cut a long strip of copper that could be nailed over it. Meanwhile a shark had arrived and was circling the boat. He fetched his rifle, shot the shark, and watched it sink out of sight, apparently without attracting other sharks. He went back into the chilly water hoping that was so.

He was successful with the copper strip, but the wind came up, and he had to postpone sealing the second gap until another calm several days later. When that one was done, his leak was fixed.

Sometimes maintenance involves shooting the shark.

But he was unable to fix the overhead leaks from poorly fitted hatch covers. That meant he would never get dry. The author of the book A Voyage for Madmen , Peter Nichols, drew on his own experience as a single-hander to describe Knox-Johnston’s situation:

“ With every wave that broke over the deck and cabin, salt water poured in through the companionway hatch and splashed over the chart table, the book rack, and the Marconi radio . . . The skylight dripped incessantly above his sleeping bag . . . A small boat at sea is its crew’s only port in a storm, and if the boat is cold and wet below, its gear beginning to fail, the dismalness of such a situation can’t be exaggerated .”

The constant motion also took a toll. Knox-Johnston noted that his tools were holding up well, except he was running short of drill bits, ‘mainly because when drilling in a moving boat one is constantly being thrown about and unless one withdraws the drill fast it gets snapped off’. He added that his health remained good, ‘apart from the inevitable cuts, blisters, and bruises’.

One night, in his first gale, he lay in his bunk listening to the shrieking wind and tumult of breaking waves and chaotic cross seas. Suddenly he was hurled to the far wall and buried under everything loose in the cabin. He dug partway out and then was flung back across into his bunk as the boat righted itself after a complete knockdown. With the lamp out, he was in utter blackness. He groped his way out to the deck and felt his way around in the violent night to see if he had any masts left at all. He was surprised to find all his rigging intact, though the self-steering gear had been damaged.

He went below to pump out all the water that had come in during the knockdown and found that more was still coming in. To his horror, it was pouring in from gaps around the edges of the cabin, which had apparently been knocked partially loose from the deck. He knew that if the cabin got torn all the way off by another capsize, SUHAILI would fill with water and sink. He reduced sail to improve his odds of surviving the night.

When the storm abated, he spent a whole day reinforcing the structure that held the cabin to the deck, another day rebuilding the self-steering apparatus, and then three days repairing the rudder. If he had not laid in a supply of materials, tools, and fasteners for such tasks, he would have had to quit the race. It was his thorough preparation that equipped him to ‘make do and mend’.

But preparation can never be perfect. The radical part of Knox-Johnston’s making-do was that he was never daunted by the lack of a crucial material or tool.

When he took apart his radio transmitter to find out why it had quit working, he discovered a wire connection so badly corroded it would have to be reattached, but he had no solder to do it with. So . . . he painstakingly melted and collected the tiny dots of solder from inside several navigation light bulbs. That got the transmitter working again. (For a while.)

Another time, he figured out that his battery charger wouldn’t run because of grease on the ignition points. He cleaned off the grease and then realized he couldn’t reset the gap at the required 12 to 15 thousandths of an inch because he had no feeler gauge on board. So . . . he measured the pages in his logbook and found there were 200 to the inch, which meant one page would be 5 thousandths of an inch. Three pages did the trick. The charger ran again. (For a while.)

In his book, he wrote, ‘Necessity is the mother of invention and I am always quite happy to leave things until I have to cope with them, and then throw myself happily into the problem’.

Coping worked well for him most of the time, but not all of the time.

People on sailboats tend to be vaguely disapproving and thus negligent about their engine. It is bulky, heavy, noisy, and hard to get at. Its prop drags in the water. Turning it on feels like a violation of the essence of sailing. But when the engine is really needed to get out of trouble, it had better work instantly.

One day Knox-Johnston wrote in his journal, ‘I decided to turn the engine today as it has not had any use for over two months’. It wouldn’t turn. Close inspection showed nothing obviously wrong. He wrote, ‘Whatever the trouble, it’s my own fault for not turning it daily. Now I have a lot of work on my hands to get it free, even if I manage that.’ He completely disassembled the engine, discovered that the cylinders were rusted solid from condensed moisture, and broke several tools failing to clear them.

At a point halfway around the world, he had no engine and no radio transmitter. Then came what felt like the final straw. He was south of Australia when his last spare for a critical part of the self-steering rig broke off and sank. He knew that sailing long distances solo was considered impossible without self-steering gear. He wanted to head to Melbourne and quit.

But first, he experimented to see if he could arrange his four sails – mizzen, main, and two headsails – in ways that would allow the boat to keep a course on any point of wind so that he would not have to steer all day and night. To his amazement, it turned out he could. But he needed some way to know while he was sleeping if SUHAILI was jibing or about to jibe, because the rigging was increasingly vulnerable to the shock of his mainsail suddenly slamming to the opposite side. His solution was to take the sideboard out of his bunk so that he would be flung to the floor when the boat heeled unexpectedly. ‘This was a very effective alarm’, he wrote, ‘and although I sustained a few bruises as a result, it was far better than damaging the boat’.

All the way across the southern Pacific, his boat took punishment. So did he. Years later, he recalled one incident:

“ When you’re looking at the stern and you see an 80-foot wave breaking at the top, stretching from horizon to horizon, don’t tell me you’re not a little bit scared . . . As the wave was breaking, I knew it was going to sweep the boat – and I realized I could not get down below where I was safe. So I just climbed the rigging and the wave covered the boat. It was me and two masts and nothing else in sight for about 1,500 miles in any direction. Then she popped up. The hatch had been knocked open, so I spent the next three hours pumping out three tonnes of water .”

By the time he turned north at Cape Horn toward England after four and a half months in the Southern Ocean, even his durable synthetic sails were disintegrating. ‘I spent more time repairing sails on the homeward run than any other form of maintenance’, he wrote. He had to devote three hours every day solely to tasks that would keep the boat sound enough to get all the way home.

Despite the endless ordeal, or maybe because of it, Robin Knox-Johnston reported, ‘I realized I was thoroughly enjoying myself’. He loved being at sea. He loved exploring the extreme limits of his competence.

Ever the responsible merchant marine officer, he concluded his book with an 11-page ‘Pilot’s Notes’, spelling out in detail everything he had learned about gear and technique on the voyage. He quoted from his journal this lesson in particular:

“ The only way to overcome my present feeling of depression is to fully occupy myself, so I cleaned and served the remaining bottle screw threads and then gave all the servings a coat of Stockholm Tar. Next I polished the vents and gave them a coating of boiled oil. Whilst I had it out I dabbed the oil on wire and rust patches .”

Doing maintenance cures depression.

Donald Crowhurst counted on his race becoming legendary. To solve his financial problems he desperately needed the money that would come with a famous victory.

Since he would be starting in late October at the back of the pack, he figured he could beat the others with his talent for innovation. His specialty was electronics. He had devised a handy radio direction finder that he sold through his tiny business. Stanley Best, the principal backer of his company – and later of his Golden Globe bid – said of him:

“ I always considered Donald Crowhurst an absolutely brilliant innovator . . . but as a businessman, as someone who had to know how the world went, he was hopeless . . . He seemed to have this capacity to convince himself that everything was going to be wonderful, and hopeless situations were only temporary setbacks .”

The most innovative form of sailboat available in 1968 was the newly developed trimaran – a central hull between two large floats. Trimarans were so light they could sail twice as fast as traditional keel boats, but they had a serious potential problem. When a trimaran tipped over, it would stabilize upside down and could not be righted. For the boat he was building, Crowhurst came up with an intricate solution. There would be a buoyancy bag at the top of the mainmast that would automatically inflate when it sensed a capsize. Then water would be pumped into the uppermost float, which would become heavy enough to pull the boat back upright.

Unfortunately, the 35-year-old Crowhurst was too much of an optimist to take into account the complications that always arise between having an idea and getting it to work. The whole rushed process of building and outfitting his trimaran became a nightmare of argument, delay, extra expense, and chaos. As a result, when he set sail at the last permitted moment on October 31st, the boat was unready. Electrical wires led everywhere, connected to almost nothing. The buoyancy bag was installed but inoperable.

And accidentally left on the dock in the turmoil of departure were all the materials needed for repairing the boat – plywood, fasteners, and rigging gear. The one thing he had in abundance was electronic parts and tools for his elaborate radio array. He over-prepared for what he knew well and under-prepared for nearly everything else.

Traditional systems (like wood-plank-keeled boats) have an advantage over innovative systems (like the then-novel plywood trimarans) in that the whole process of maintaining traditional things is well explored and widely understood. Old systems break in familiar ways. New systems break in unexpected ways.

Once at sea Crowhurst’s boat began to torture him with its problems. His self-steering gear was so poorly secured to the deck that it kept vibrating the screws loose, and some fell out. ‘That’s four gone now!’ he wrote in his journal. Can’t keep cannibalizing from other spots forever!’ He had to take screws from elsewhere because he had brought no spares.

The hatch in the cockpit floor leaked and let in a deluge of salt water on the electrical generator, shutting down his treasured radios. He discovered that his bilge pumps couldn’t work because the specialized piping they needed was never put on board. All the water that kept coming through leaky hatches into the floats and main hull had to be bailed out by hand with a bucket. That would be impossible in a storm, he realized.

It became clear that his boat had so much going wrong that it could never survive the Southern Ocean gales. He knew he should quit the race, but he couldn’t bring himself to do it. Then he found a way not to.

When he got the generator and radios working again, his brief communications with the world became increasingly vague about where he was exactly. In parallel with his accurate logbook, he began writing a second, fraudulent logbook with plausible positions and speed that showed a fictional Crowhurst on track to win the race. The real Crowhurst was dawdling south in the Atlantic Ocean that he now planned never to leave.

He was only as far as Brazil when he discovered an extremely serious three-foot-long split in his starboard float. Damage like that would have been an honorable reason to quit the race and go ashore, but he had already cabled to the public that he was making good time 3,700 miles east of where he actually was.

Lacking the materials for repair, he flouted the race rules, snuck ashore in Argentina, lied to the locals about who he was, repaired the split with their plywood, and headed back to sea, continuing his sporadic cheery reports of rapid progress past Africa, Australia, and South America, disguising his radio signal so it seemed to be coming from those continents.

Optimists like Crowhurst – and me, I confess – tend to resent the need for maintenance and resist doing it. Maybe we prefer to think in ideals, and the gritty reality of everything constantly decaying and breaking offends our sense of the world. Crowhurst referred to doing maintenance as ‘sailorizing’. To keep himself motivated, whenever he completed something unpleasant, he would reward himself with a drink. Before long, he was running out of rum and wine.

In his journal he would diligently make a list of projects that needed to be done, do a few of them half-heartedly, and then lose interest. Since he never got around to organizing his stowage, he had to ransack everywhere to find things.

Months went by. Crowhurst got as far south as the Falklands and then headed back toward England and the finish line.

Crowhurst was so good at fixing radios he sought out reasons to do it while neglecting everything else. Toward the end of his trip, when his long-range transmitter was irreparably broken, he decided to convert his short-range radiotelephone to long-range Morse code capability. With no technical manuals on board, he derived what needed to be done from first principles. Testing gear he had to make from scratch. Sixteen hours a day for two weeks in tropical heat, he toiled over the innards of the radios. The whole cabin was covered with electrical parts.

And he succeeded! For a day, he exchanged cables with his backers, his wife, and the BBC. Then he got more ambitious. Longing to communicate by voice, he worked on the radio far into the night, trying to convert it from low-frequency Morse to high-frequency speech transmission. This time he failed.

On June 23, 1969, he sent a cable to his wife apologizing that they would not be able to talk, and another cable to the Sunday Times (who believed he was completing the fastest circumnavigation), asking permission to have transmitter parts delivered to him. Their answer was no.

It was his last sane day.

Crowhurst had been broadcasting an elaborate lie for seven months. By now he was sure he would be found out. He might be received back in England in triumph at first, but once his fake logbooks were examined closely, it would all turn to scandal and disgrace. His financial ruin would be complete. He would have failed his wife and four children. The prospect was intolerable.

On June 24 he began to take hope from a tremendous new idea that he was certain would liberate him and all of humanity if he could just explain it clearly enough. Adrift in the Sargasso Sea, he spent the next eight days and nights feverishly spelling out in his journal the origins and wondrous ramifications of his discovery that reality could be stipulated by a sufficiently brilliant mind. Abstraction was the ultimate power. The realization led to exhilarating revelations. In one statement that ended with 18 exclamation points, he wrote:

“ And yet, and yet – if creative abstraction is to act as a vehicle for the new entity, and to leave its hitherto stable state it lies within the power of creative abstraction to produce the phenomenon!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! !”

He was confident that when mathematicians and engineers read what he was writing, they would understand it immediately, and ‘problems that have beset humanity for thousands of years will have been solved’.

With intense delusional invention he was trying to solve his own problem.

Midmorning on July 1, 1969, he saw with dismay that his chronometer had run down. He started the clock again in order to keep precise track in his logbook of his countdown, insight by written insight, to the moment that would resolve everything. At 10:29:00 he wrote:

“ It is finished IT IS THE MERC Y”

The last entry read:

“ 11:17:00 It is time for your move to begin I have not need to prolong the game It has been a good game that must be ended at the I will play the game when I choose I will resign the game 11:20:40 There is no reason for harmfu l”

Having come to the bottom of a page, he did not complete the sentence.

Instead, taking the clock with him, he went out on deck and crossed his own finish line into the ocean – leaving behind the boat and the documents that he knew would reveal the truth of what had happened. He could have disguised his suicide as an accident and chose not to.

The trimaran was found nine days later by a British ship and hoisted aboard intact.

The tragic story of Crowhurst’s deception usually ends with the note of redemption in his words ‘It is the mercy’, but this is the maintenance version.

He was a remarkable man, intelligent and bold. The boat he abandoned, however, revealed how lax he was about nearly every aspect of maintenance. The exhaustively researched book The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst by Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall has this indicative example:

“ The cabin, after eight months of cramped, unmethodical male housekeeping, smelled as if cabbage juice had been poured over old bedding, allowed to ferment, then baked in a hot oven. Several days’ plates, saucepans, and ripening curry lay in and around the sink; his bed stank. “

The authors added, ‘This smell was still pungent five months later’.

Poor preparation and maintenance led to Crowhurst’s cheat. The cheat led to his death. His excessively optimistic view of the world and himself, which had worked fine on land, was lethal for a man alone at sea in an unfit small boat, marinating for months in two contradictory realities. He had invested so much of himself in an illusion that when it shattered, he shattered.

Bernard Moitessier (pronounced “Mwa-TESS-ee-ay”), at 46 years old, was the most experienced of the nine Golden Globe competitors. For years he had vagabonded alone in small boats all over the world and then, in 1966, made an epic trip sailing with his wife from Tahiti to Spain via Cape Horn. At the time, it was history’s longest nonstop passage by a yacht.

Compare Moitessier’s first knockdown in the Roaring Forties with what three of his competitors experienced.

You’ll recall it took Robin Knox-Johnston five days of repair to recover from his capsize. Another sailor, Loïck Fougeron, endured something similar. Beset on his 30-foot steel cutter at night in a gale, he was violently thrown to the side of his cabin and buried under all his stuff, certain he was going to die. When the boat came upright, he decided instantly to quit the race and sail to shore in Africa.

It was even worse for Bill King. His 42-foot junk-rigged schooner was thrown over on its side by a massive wave and then turned all the way upside-down. When it finally came back up, his masts were broken. By sheer luck, King happened to be in the cabin fetching a rope when the knockdown occurred. If it had come 30 seconds earlier or later, he would probably have died. Under a makeshift rig he also sailed to Africa to quit.

Moitessier’s turn came in a fierce storm with rough cross seas. He was relaxing in the cabin. He wrote, ‘I put on my slippers and roll myself a cigarette. A spot of coffee? Why not! God, it’s good to be inside when things are roaring out there.’

Suddenly, ‘an enormous breaking sea hits the port beam and knocks us flat’. After his boat came back up, Moitessier went on deck to check for damage and make adjustments to the sails. The aft boom had swung and broken the wind vane off the self-steering gear. He wrote: ‘Not serious: half a minute is all it takes to change the vane, thanks to a very simple rig. I have seven spare vanes left, and material to make more if necessary.’ The boat sailed on as if nothing had happened.

Moitessier had dealt with most of his maintenance issues in advance . Everything about the design and construction of his boat and everything about his outfitting for the race was a result of his decades of learning exactly what it takes for a small boat to thrive in the brutal Southern Ocean. He knew that once at sea, the need for maintenance had to be minimal, and doing it had to be easy.

The boat was named Joshua – after Joshua Slocum, the first person to sail around the world alone (though with many stops along the way). It was a traditional two-masted ketch like Knox-Johnston’s, but at 39 feet, it was seven feet longer and therefore faster. With money from an admirer, Moitessier had it built of heavyweight steel at a boilerplate factory in France. ‘Ah, steel’, he wrote. ‘Watertight bulkheads, tanks welded right to the hull, incomparable rigidity, welded chain-plates, and an absolutely watertight boat that you clean with a broom and dustpan instead of a bilge pump.’

The critical maintenance issue with steel is corrosion. The answer, he wrote, is ‘paint, paint, and more paint’. Noting that the French Navy puts on ten coats of paint before any launch, he went with seven coats, but notjust any paint. It had to be what he considered the best paints in the best sequence – in his case, two coats of anticorrosion zinc silicate Dox Anode, followed (after two weeks of drying) by two coats of a zinc chromate paint and three coats of two-part epoxy. (Obsession with detail is a hallmark of the most successful maintainers.)

For additional strength and simplicity, JOSHUA’s masts were recycled telephone poles. He installed steps up the side of the masts so he could comfortably climb them weekly to inspect for problems and oil the halyard blocks at the top. Far more important, he would be able to reach the mastheads instantly in an emergency.

‘The one thing that any singlehander fears’, Knox-Johnston wrote, ‘is something breaking at the top of the mast’. Like most sailboats, Knox-Johnston’s SUHAILI had no mast steps. He had to hoist himself aloft in a bosun’s chair, which could only be done safely in a dead calm. He tried it once in rough seas when a halyard broke, and he could no longer raise or lower his mainsail. Thirty feet up in the chair, he was flung away from the mast and nearly killed.

Moitessier’s sails were made of the same high-strength synthetic as Knox-Johnston’s, but he had no need to spend countless hours repairing them because he had his made ‘small, light, easy to handle, with very high reef bands and reinforcements that would take a sailmaker’s breath away’. He was six months at sea before he had to get out his sewing palm at all.

He even added a unique element for heavy-weather sailing. In order to steer JOSHUA from inside the cabin, he made a small windowed dome out of a washbasin and attached it to the roof of the main hatch. Perched safe and dry on a seat under the dome next to the interior wheel, he could see conditions outside and adjust his course as needed.

‘JOSHUA is just simple’, Moitessier once told an interviewer. ‘Simplicity is a form of beauty.’ That principle governed everything for him. ‘Given a choice between something simple and something complicated’, he wrote, ‘choose what is simple without hesitation; sooner or later, what is complicated will almost always lead to problems’. Only simple things, he noted, can be reliably repaired with what you have on board.

His self-steering gear was easy to repair because it had none of the usual complicated linkages or line attachments. He didn’t bother to install interior heating because, thanks to a watertight cabin, reliably dry clothing would keep him warm enough.

He hated electronics on boats, so there was no battery charger to worry about. To substitute for what he described as ‘two or three hundred pounds of noisy radio equipment’, he had a slingshot for launching film canisters containing his messages onto the deck of passing ships. His cabin light was a kerosene lantern.

Moitessier emptied his boat of absolutely everything but the basics. With less stuff, there was less to maintain. With less weight, he would sail faster. Before departure he off-loaded his engine, his dinghy, four anchors, 900 pounds of anchor chain, the anchor windlass, surplus books, surplus paint, and half of the water he usually carried. It added up to a ton of weight and distractions gone. Later at sea, he purged still more – heaving over the side 375 pounds of food, kerosene, and rope he decided he wouldn’t need.

Thanks in part to his paring down, though he had left England more than two months after Knox-Johnston, he was sailing so much faster he might well catch up.

As Moitessier approached Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, he wanted to let the world know what a sensational passage he was having. He sailed up to a freighter and slingshotted a message onto her deck, saying he had two packages of information to throw to them. Their skipper obliged by turning the stern toward him, and the packages were passed.

But then the overhanging stern of the freighter caught Moitessier’s mainmast. He wrote: ‘My guts twist into knots. The push on the mast makes JOSHUA heel, she luffs up toward the freighter . . . and wham! – the bowsprit is twisted 20 or 25 degrees to port.’ He was horrified.

His bowsprit was a steel pipe, so it bent instead of broke, but he knew he could not continue the race if it stayed bent, because the symmetry of the stays that supported his masts was now so compromised he could lose his whole sailing rig in a storm. How could he possibly fix it at sea alone? He wrote, ‘I did not want to crystalize my thinking prematurely’. He thought about the problem for two nights and a day before proceeding.

His carefully considered solution was elegant, combining a four-part block and tackle with his cockpit winch for sufficient force and using a staysail boom to get the right leverage. Bowsprit straightened, he sailed on, exultant.

I once got to know Moitessier a little bit. In 1981 he was living aboard JOSHUA in Sausalito, California, close to where I had a sailboat berthed. One time, when I remarked on how fit his boat looked, he said, ‘My rule is, a new boat every day’. His years at sea had taught him that if you don’t fix something when you first see it beginning to fail, it is very likely to finish failing just when it is the most dangerous and the hardest to deal with, such as in the midst of a storm.

He loved doing routine maintenance. He wrote:

“ I work calmly at the odd jobs that make up my universe, without haste: I glue the sextant leg back on with epoxy, adjust the mirrors, replace five worn slide lashings on the mainsail and three on the mizzen, splice the staysail and mizzen halyards to freshen the nip on the sheaves .”

His reward for a boat functioning like new every day was this: ‘I spend my time reading, sleeping, eating. The good, quiet life, with nothing to do.’ That was in fair weather. Storms were as arduous for him as ever, but he was unafflicted with worry that his gear might fail.

He also took care to maintain his own health, physical and mental. When he found himself exhausted after rounding the Cape of Good Hope, plagued by an ulcer and considering giving up, he began doing yoga every day. ‘My ulcer stopped bothering me’, he wrote, ‘and I no longer suffered from lumbago. But above all, I found something more. A kind of undefinable state of grace.’

Moitessier was at the peak of his skills – at one with his boat, one with the sea, one with himself. He began wanting it to go on and on.

All across the Southern Pacific he was catching up to Knox-Johnston, who had started 69 days before him. They rounded South America’s icy Cape Horn only 20 days apart, with 10,000 miles to go to England. The London press began predicting that Moitessier would not only win the £5,000 prize for the fastest solo round-the-world trip, he might also finish first, taking the Golden Globe award as well. France was preparing a fleet of naval ships and yachts to accompany their hero home, where he would receive the nation’s highest tribute, the Legion of Honor. No yachtsman in the world would be more famous.

Moitessier dreaded all that. He wrote, ‘I really felt sick at the thought of getting back to Europe, back to the snakepit’. He asked himself, ‘How long will it last, this peace I have found at sea? . . . Don’t look beyond JOSHUA, my little red and white planet made of space, pure air, stars, clouds and freedom.’

And yet he longed to see his wife and friends. He could really use the prize money. What had he sailed so fast for, if not to win?

Race watchers in England calculated that Moitessier must be far up the Atlantic toward a double victory when word came from South Africa of a message received by slingshot on a tanker in Cape Town Harbor. It read:

“ My intention is to continue the voyage, still nonstop, toward the Pacific Islands, where there is plenty of sun and more peace than in Europe . . . I am continuing nonstop because I am happy at sea, and perhaps because I want to save my soul .”