How to Heave To On A Sailboat

If you’re wondering how to heave to on your sailboat, and why you might want to, then you’re reading the right article!

Heaving to is an important safety technique that every sailor should know, and practice regularly. But do you know how to heave to, and under what conditions might need to use this manoeuvre?

In this article we take a deep dive into the practice of heaving to – exploring how to enter a hove-to state on different kinds of sailing vessels, when and why to use this technique, and taking a look at some historical examples of instances where heaving to has saved lives.

You can trust us to tell you everything you need to know about the heave-to manoeuvre, because we are seasoned sailors with RYA-accredited qualifications and thousands and thousands of miles under the keel, hard-won in every sea state imaginable. We have also heaved to quite a few times ourselves!

Before we get into the mechanics of how to heave to, let’s take a quick look at what this technique is and aims to achieve.

Table of Contents

What is heaving to, why heave to in sailing, how does heaving to work, how to heave to in a sailboat, how to heave to in a sloop.

- How to heave to in a cutter

- How to heave to in a ketch

How to heave to on a catamaran

Heaving to as a storm tactic.

Heaving to is a manoeuvre that sailors can use to slow their vessel down to a near-crawl, while fixing the helm and sail positions so that the crew no longer need to actively steer the boat or manage the sails.

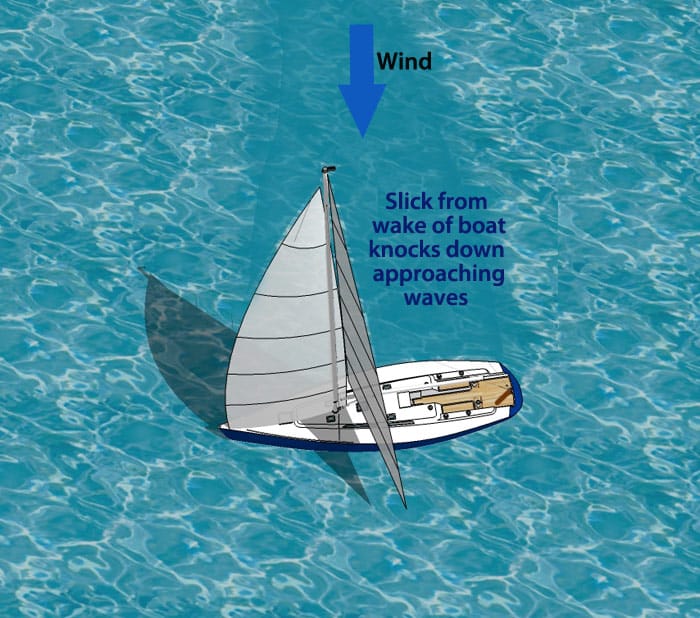

When performed correctly it will also place the bow of the boat at angle up into the waves, allowing her to ride them smoothly and producing maximum comfort for all aboard. It should also minimise leeway.

As we’ll see in a moment, the exact technique to achieve these outcomes varies by the kind of sailing boat you have – principally, by her sail plan.

You may occasionally hear power-boaters use the term “heave to” to simply mean throttle back and come to rest. In this article, we’ll mostly be talking about the technique of heaving to under sail instead.

Heaving to is an important safety manoeuvre commonly used to sit out heavy weather, allowing the crew to go below, take a rest and get warm and dry. A correctly hove-to boat can sit out most kinds of weather, just bobbing along on the top of it.

Heaving to can also be used as a low-effort way to simply wait in position for a time, such as when waiting for tides to turn, a squall to blow past ahead, or for a bridge to open.

Some sailors have been known to heave to just to have a cup of tea and a biscuit!

Another application is stopping the boat in a hurry while under sail. For this reason, it’s used in some man-overboard recovery techniques. Naturally, you can dump the sheets to achieve a similar outcome, but that doesn’t apply reverse thrust in the way that backing a sail does.

When it comes to MOB scenarios you could heave to in order to stop the boat rapidly, then engage the engine, throw the sails down and proceed to recover the MOB under power.

Or, if you intend to recover the MOB under sail, you can approach them while hove-to in order to drift up to them slowly.

Not everyone agrees that heaving to is the correct way to initiate an MOB; a lot of sailors advocate for letting the sheets fly instead, forgetting about the flapping canvas and getting the motor on as soon as possible.

You’ll see a lot of complicated explanations online for how heaving to actually works. We think most of them overcomplicate things, and generally prefer to explain it like this:

Heaving to works by backing the headsail so that it fights the mainsail. If you get it right the two sails cancel each other out and the boat stays more or less static, despite being powered up.

That’s not quite the whole story, but it’s by far the easiest way to visualise what’s happening on a hove-to boat.

To initiate a heave-to, you proceed as though you are going to tack the boat, but do not tack the headsail sheets or adjust the headsail in any way. The main, of course, will self-tack, but the headsail (or storm sail ) needs to be blown backwards through the triangle formed by the mast and the forestay, and end up backed – with the belly facing inboard – rather than outboard as it usually would.

Still with us? If you’re lost, think about it like this: you are literally just performing a normal tack without tacking the headsail sheets. At the end of the manoeuvre, you will have a normal, correctly tacked main, but a headsail that is backed and still sheeted as though you were still on the opposite tack.

The result of this is that the mainsail powers the boat forwards normally, but the headsail is backed and resisting it, pushing it backwards; so the boat achieves a state of near-equilibrium and simply drifts.

You should only be travelling at around a knot, but the boat is still powered-up and stiff rather than at the mercy of the waves, and therefore orders of magnitude more comfortable than if you had put the sails away.

That’s the flavour of it: now let’s look at exactly how to heave to on a sailboat, step-by-step.

When heaving to, we’re always trying to achieve the same thing: to get the headsail and the mainsail balancing each other out, so that the boat is still powered-up and comfortable, but no longer making any headway.

Generally speaking, we achieve that either by tacking a sail, but not the boat; or the other way around – by tacking the boat, but not one of the sails. Either way, we end up with one sail fighting the other, and the boat comes to a stop.

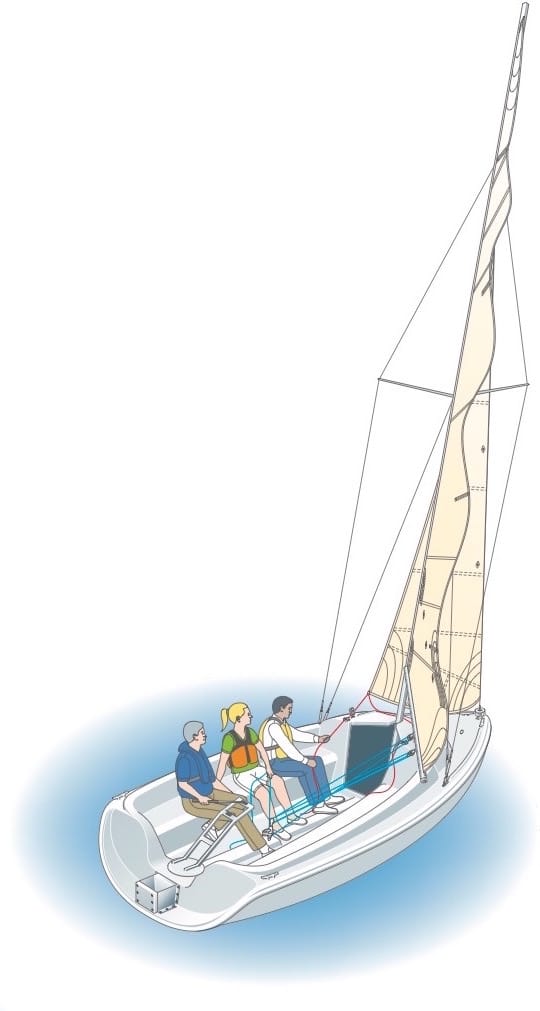

The exact procedure to enter a hove-to state is different for different kinds of sailing vessel and rig, so let’s start with the simplest scenario: you are a sloop, with one mast, a mainsail and a jib.

There are two ways for a single-masted sailing vessel such as a sloop to begin a heave to. For both of them, you want to be travelling upwind.

The first way is to literally heave the jib over to the “wrong” side of the boat, i.e. the windward side. This means releasing the leeward sheet and manually hauling the sail through the gap between the forestay and mast using the windward sheet.

It sounds complicated when you spell it out like that, but it’s literally the same set of steps you would follow to tack the headsail, just like normal- except you don’t tack the boat.

The jib moves, the wind doesn’t, so the jib ends the manoeuvre backed and pushing backward against the main; which is still on the correct tack, powered up and propelling the boat forwards.

The alternative is to tack the boat but not the jib.

In other words, the helmsman swings the wheel to wind; the bow of the boat tacks as you would expect, but at the point the crew would normally scramble to release one jib sheet and tension the other to tack the headsail (the moment your helmsman booms “lee ho!” , if you’re that sort of boat) – you instead do nothing.

The jib ends up backed again, because nobody tacked it. The main self-tacks and re-powers on the new tack, and the two still end up counteracting each other. Personally, we feel this is much easier, as you don’t have to manually heave the jib back through the gap between the forestay and mast – you just turn the helm.

Tacking the boat also slows you down a lot right away, which is one of the goals of heaving to in the first place.

Whichever of these two methods you use, the next step is to turn the wheel to windward – as though you are trying to tack back again. Of course, you will not have the speed or drive to do this with a backed headsail.

The purpose of turning the helm to wind like this is threefold:

One, we need to stay head-to-wind to keep the headsail backed. If we bear away, the headsail will fill and we will exit our heave-to.

Two, heaving to doesn’t truly stop the boat. You will still be making a knot or two through the water. This is actually desirable, because you will also be making leeway. By pointing upwind, we aim to use that knot of speed to counteract the leeway and remain more or less stationary over ground.

Thirdly, we want the bow of the boat to be facing up into the waves, at an angle, because that’s a lot more comfortable for the crew than taking them on the beam.

Start by turning the wheel to wind by hand and finding the point at which the boat settles down and maintains a steady course to wind and wave. You can lash the wheel there if you desire, and then you’re free to go below.

If she doesn’t want to settle down, or you’re making too much headway over ground, you may need to ease the sheets or even take a reef in the main.

It’s important to try heaving to in different conditions so that you know how your particular vessel performs, before you need to perform the manoeuvre in anger. Old, heavy-displacement, full-keel boats are often much easier to heave to than modern fin-keelers.

How to heave to on a cutter or Solent rig

Cutters and Solent-rigged sailboats have a single mast, like a sloop, but they have two headsails. The addition of an extra headsail makes heaving to a little more difficult.

The primary headsail on a cutter is usually a large genoa that attaches at the masthead and runs to the bow, or often to a bowsprit enabling a larger sail. This is usually the sail we will be backing in order to heave to.

The second headsail on a cutter is usually called a staysail, and attaches about a quarter of the way down from the masthead. This second, smaller headsail is often set up to be self-tacking.

When you want to tack a sloop, you only need to pull the headsail through the very large gap between the forestay and mast. When you want to tack the genoa on a cutter, you have to fit that extremely large sail through the much smaller gap between the outer and inner stays.

The upshot of all this is that it’s harder to back the sail on a cutter. You can either drag it laboriously through the gap using the winch, or someone can go forward and manhandle it along – but that’s not always the safest in heavy weather.

When it comes to a Solent rig, it’s usually much easier. A Solent does have two headsails, but the outer one is usually a cruising chute and the inner one is the jib. As such, to heave to on a Solent-rigged boat, you perform the exact same steps as on a sloop.

How to heave to on a ketch or a yawl

Twin-masted sailboats, such as ketches, can also heave to.

These vessels have a main mast and a second, smaller mast called a mizzen, and can fly sails from both masts. The difference between a ketch and a yawl is the size and position of this aft mast.

Most ketches and yawls fly a headsail, a mainsail, and then a smaller mainsail from the mizzenmast called a mizzen sail. In other words, only the main mast has a headsail.

You do get mizzen staysails that sit between the main and mizzen masts but they’re rare. To all intents and purposes, we’re dealing with three sails here, and two of them – the main and mizzen – are self-tacking.

The principle to heave to on a ketch or yawl is similar to a sloop: we’re still looking to balance the sails, by backing the headsail and leading the main powered up.

Because the mizzen behaves like a small main, we treat it like one and let it self-tack along with the main. As a result, in our hove-to position, we have a backed jib, and a main and mizzen flying regularly.

We now turn the wheel to windward and use the tension on the mizzen sheet to adjust how high or low we point into the wind and waves. We can also use the tension on the main sheet to influence how much headway we make.

Most catamarans actually can’t heave to. When a monohull heaves to, part of what makes it work is the action of the sails pivoting around the keel – and the keel provides drag and dimension stability that reduce leeway.

Catamarans don’t have keels. At least, not deep keels with heavy ballast bulbs. They can have fixed, stubby little mini-keels, or long retractable daggerboards – but either way, their keels act like the fins on a surfboard rather than ballast. They also have two of them – they just don’t behave in the same way as monohulls.

Cats do have a few heave-to-adjacent manoeuvres that they can turn to in a storm, though. The first is to deeply reef the main, drop the traveller all the way to leeward, and then pull the mainsheet in hard. Lash the helm so that the cat is on a safe, close-hauled course. If you get it right, you should be drifting sideways calmly at about half a knot, with your bows into the waves at an angle.

This is sometimes called “parking” a cat. Performance cats with daggerboards, when performing this manoeuvre, should leave both boards about halfway down.

Performance cats also have the option to pull the boards right up and skate freely over the surface of the waves; either with or without sail power.

Performance cats are fast, so as long as there’s enough room to run, they also have the option to turn down wind and match the cadence of the wave train – creating a smooth ride with minimal wave impacts. They also ride higher on the waves as they accelerate, effectively creating more reserve buoyancy.

When sailing in heavy weather in a catamaran, however, it’s important to remember that cats don’t heel and it can be harder to tell when one is overpowered. They also don’t spill wind and self-compensate in the way that a heeling monohull does, so it’s wise to reef early and often.

Heaving to as a storm tactic exploded in popularity, particularly in the RYA syllabus, after the 1979 Fastnet disaster.

The 605-mile race is held once every two years off the coast of the UK. In 1979, it was struck by a terrible storm; more than a hundred boats capsized and 19 people died.

Hundreds more would certainly have been lost if not for the brave actions of an unbelievable, impromptu volunteer search and rescue operation – the largest ever in peacetime – consisting of more than 4,000 members of the public and pleasure boat owners.

It was later discovered that every single boat that had heaved to had emerged from the storm completely unscathed. Every boat that capsized or been knocked down had either attempted to carry on sailing, or had used a different technique called “laying ahull”.

In the aftermath of these events, the RYA took it upon itself to disseminate the information that heaving to saves lives, and they continue to recommend it as a storm tactic today.

As noted earlier in the article, not all boats actually can heave to, but if your boat is capable, it’s certainly a valuable trick to keep up your sleeve. It’s a good idea to read up on how sailing your sailboat in a storm just in case you need to employ other tactics.

In conclusion, heaving to is an important safety technique that every monohull sailor should be aware of. At a basic level, it provides you with a window of calm and safety to gather your thoughts and take some refreshments. At the extreme end of the scale, it could save your life in a storm one day.

It’s important to practise heaving to before you need to use the technique for real, because every boat performs a little differently. This goes double if you intend to incorporate heaving to into your man overboard protocol.

Heaving to isn’t a particularly difficult technique, but you do need to try it out a couple of times in order to get comfortable with the sail and trim your particular vessel requires to settle down into a nicely hove-to state.

Similar Posts

Bottom Paint For Boats: Your Options 2024

The Best Action Camera For Travel Vloggers 2024

Sailboat Storage Ideas For The Organised Sailor!

Sailing With A Baby: Essential Guide 2024

Sailing Terms: A Complete Guide 2024

101 Awesome Boat Puns And Yacht Captions For Instagram 2024

Sailing Tips: How To Heave To

The ability to heave-to is a key part of seamanship that can keep you safe on the water in any breeze strength.

Throughout this article, we will discuss the basic requirements and steps necessary to heave-to and the advantages of doing so in various conditions. We will go through the basic physics of the position and help you to understand why it is such an effective way to slow down your boat.

While there are various positions that are roughly equivalent to heaving-to, including the safety position for smaller boats and fore-reaching in certain conditions, this is a highly useful skill that gives you a good balance of safety, position holding, and quick maneuverability while on the water. It may require some practice and a few erstwhile attempts before you get the complete hand of it, but in situations where you want to put the brakes on without anchoring your boat, heaving-to is a great solution!

As a certified small boat instructor, I have helped all levels of sailors learn how to perform this maneuver in dinghies and similar boats, but its utility is further extended for keelboats and other cruising classes, including catamarans and trimarans. From my conversations with cruisers and a bevy of research, I can assure you that, as long as you’ve got a mainsail and a headsail, this is a viable option for your needs. Maybe I’ll even be able to give you an insight or two into the physics of the whole setup, but first, let’s take a look at the basic premise and a few steps that will help you get there.

Table of contents

The Basics of the Heave-To

While highly maneuverable and not always the easiest to execute, the fundamental premise of the heave-to is not terribly complicated.

Though the balance and the angle will be slightly different depending on the boat and the breeze, there are four basic characteristics of heaving-to.

Angle to the Wind

Though not explicitly included in the diagram, you should expect to be somewhere around 45-50° to the breeze while in this position. This should be far enough from the breeze that your main is not luffing too hard, but close enough that you aren’t powering up too much.

Jib to Windward

Now this is the most important characteristic of heaving-to. While normally frowned upon, and potentially dangerous when unanticipated, backing the jib like this is what gives you stability in this position. You trim the jib, genoa, or other similar headsail with the windward sheet and keep it locked down. If heaving-to in heavy breeze, it is good to employ a storm jib or to reef your headsail if possible to keep it from being too tensioned up in this position, as a big gust could pull your bow well off the breeze and cause trouble.

Main Trimmed

Trimming the main in this position serves two purposes. First, it balances out the jib's pull to turn downwards. This is why you would not take the main down when attempting to heave-to. Second, it preserves the main from the luffing that will age it very quickly. Moreover, if you want to exit this position, you already have your main set for the close-hauled course that you would take on right afterward. Similarly to the jib, you may find that reefing the sail helps in heavy winds, or is useful in balancing the sails overall.

Tiller to Leeward

Keeping the tiller to leeward helps you maintain this position in two ways. First, it continues to balance the jib’s attempts to draw you off the breeze. Second, by opening the rudder’s face to the water flowing under the boat, you are essentially using the rudder as a sea anchor, helping you to slow down even more and continue to hold your position.

These four steps are the baseline characteristics of heaving-to. How this will work on your boat depends on many factors that you cannot necessarily control or anticipate before you get on the water. That is why, rather than giving you a detailed boat by boat procedure, we are going to talk about some of the fundamental physics that you are working with when heaving-to, so that you know how to adjust for yourself when certain things are happening the first few times you try this out.

The Physics of Sail Control

In the type of boats with the headsail-mainsail sail plans where heaving-to is most effective, be it a catamaran, trimaran, keelboat, winged-keelboat, or simple dinghy, there are a few basic forces with which you have to contend while maneuvering of which heaving-to takes advantage. In order to talk about that, however, we first have to deal with

Centers of Effort and Resistance

In sailing in general, the goal of upwind sailing is to balance what we call the ‘center of effort’ with the ‘center of resistance.’

The center of effort is the theoretical point on your sails from which you generate all of the lifting force for forward motion. It is essentially the engine of your sails and the mathematical center of the sail plan.

The center of resistance is the point somewhere underwater on your hull -- on a keelboat it will be somewhere close to that keel -- which provides the lateral resistance that helps your boat move forward, rather than sliding with the wind.

Ideally, your boat is set up so that when you are trimmed to go upwind, the center of effort is directly above the center of resistance. Once you do this, all that lift generated by the center of effort is channeled forwards by the center of resistance. If they are misaligned, or your sails are overpowered for your boat, you will slide laterally. This is why over-heeling your boat to leeward tends to be slow and cause you to sleep sideways, as this effectively reduces the resistive force. Thus reefing, even though it lessens your sail area and reduces the lift generated, actually helps you go forward in heavy breeze as it keeps you from heeling as much and ensures that your centers of effort and resistance are still lined up.

But I digress. The real point of this is to talk about…

Sail Trim and the Center of Effort

Since controlling the balance of the center of effort is crucial to keeping your boat moving, it is useful to know how each sail affects the center of effort. On most boats, the center of effort is at the deepest part of your mainsail, called the draft, about ⅓ of the way back on that sail. This means that you can consider that as the central axis of your boat.

If you move to trim your jib -- or genoa or other headsail -- you are essentially adding more force forward of that central axis, which, in turn, pulls the bow of your boat down, away from the wind. If you overtrim your jib or, even worse, backwind it coming out of a tack, you will feel your boat pulling downwind towards a reach, or even dead downwind if unchecked.

On the other hand, if you move to trim your main in, you will be adding more pressure to the back half of your main, effectively turning your bow upwind (you can even think about it as pushing your stern downwind!).

It is this balance of jib trim and main trim that keeps your boat sailing forwards and your rudder light and helm-free. You can, in fact, use this phenomenon, along with some bodyweight steering in smaller boats, to effectively sail your boat without a rudder, either for fun or in case of a breakdown. Many double-handed race teams actually do this to practice perfecting their sail trim!

Using this to Heave-To

Ok, ok, that’s a lot of that talk, but how does this help you figure out how to find the perfect heave-to balance for your boat. Well, it actually gives you a pretty good sense!

Heaving-to takes advantage of this balance and flips it on its head. Instead of using these characteristics of the main and the jib to propel you forward, heaving-to uses them to stall out your boat entirely. By trimming the jib to weather, a move that would normally tear you down to a beam reach in a second, keeping the main working, and throwing the tiller over, you effectively have fixed your boat somewhere around 45° to the wind.

If you think about the relationships a little more, you see that each of the three main controls, jib, main, and tiller, are effectively keeping each other in check. The jib cannot pull you off the breeze because of the dual action of the main keeping the stern down and the rudder turning the boat back upwind if it gets any flow. The main will not propel the boat forward because the backwinding of the jib is choking off its airflow, and even if it did get moving it would push too close to the breeze and start luffing. Finally, the rudder, positioned as it is, both acts as a brake against the water underneath and helps keep the boat from turning down, which could end this game of dynamic tension.

Troubleshooting

Because this balance relies so much on the individual characteristics of your boat, it is difficult to say exactly what trim settings you will need to maintain this position for a long time. Therefore, it is up to you to experiment!

If you find that your jib is overpowering your mainsail, pulling you off the breeze, you may have to either reef the jib, push the tiller over farther, pull the jib farther to weather, or get more power in the main. With the opposite problem, you may find it necessary to reef the main quite a bit, or find a better way to haul your jib to weather. It is good to have a rough guess of how to set your boat to heave-to in various wind conditions, as it may be different across sea states and breeze strengths, so I would encourage you to try it out a few times on a few different days so that you know before you need it!

How to Heave-To

After all of that, I would be remiss not to give you the rundown of the easiest way to get your boat in the heave-to position. While it is occasionally possible to simply sail upwind, luff your sails for the moment, and heave your jib to weather, this is not necessarily the most efficient way to do it, and it can put excessive strain on your sails and sheets (and yes, that really is why they call it ‘heaving-to!’).

In general, you accomplish the heave-to by sailing upwind then turning your boat into a nice, slow tack. As you do this, keep your headsail trimmed to the sheet on the old tack, so that when you come out of it, you are trimmed on the weather side.

As you come out of the tack and the backwinded jib is trying to pull you off the breeze, keep your tiller pushed, or wheel turned, to leeward. If you don’t overdo it, the fight between the jib pulling you down and the rudder turning you up should stall your boat out so that you are more or less stopped in the water. Throughout this whole process, the main should be trimmed-in, approximately to where you have it when sailing close-hauled, a little looser if anything, but not luffing.

When you find the point where the main is not ragging, the jib is full but not pulling you down, and the tiller is set, you have effectively heaved-to! Again, finding the right balance may not be that easy, and may require various reefing, trimming, and steering adjustments. These are too many to count, which is why I hope the explainer on the various forces that you are trying to balance will help you diagnose any potential issues you have so that you can make these adjustments as you go!

You should find that this is a highly effective way to stop your boat without the need to drop anchor or your sails. In fact, the little forward progress that you will make from the fact that your sails are still filled should be just about enough to keep your position against the wind and the waves, which would drive you backward in any other unanchored arrangement.

Like anything else in sailing, however, it takes a few attempts, a couple of tweaks, and a good feel for your own boat to master the heave-to, so I hope you take this as a good excuse to get back on the water. Happy Sailing!

Related Articles

Gabriel Hannon

I have been sailing since I was 7 years old. Since then I've been a US sailing certified instructor for over 8 years, raced at every level of one-design and college sailing in fleet, team, and match racing, and love sharing my knowledge of sailing with others!

by this author

How to Sail

Most Recent

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

Daniel Wade

October 3, 2023

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

How To Choose The Right Sailing Instructor

August 16, 2023

How To Sail From California To Tahiti

July 4, 2023

How To Tow A Skier Behind A Boat

May 24, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

June 15, 2022

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

My Cruiser Life Magazine

How to Heave To – Complete GUIDE

Sailboats are a little bit like airplanes in some ways. Their sails work like wings, sure. But they also cannot be stopped. If you want to come to a stop in a car, you can stomp on the brakes. If you are in a powerboat, you can kill power to the motor and drift to a stop. But what do you do in a sailboat, when the sails will continue producing power once they are set – just like a plane cannot stop in the sky.

The answer might surprise you. An airplane can’t stop, but a sailboat can – sort of. The answer lies in a maneuver called heaving to.

Table of Contents

What does heave to mean, windward sheet handling, main sail trim, rudder position, getting out of the hove to position, heaving to on a catamaran, how to heave to with a self-tacking headsail, storm jib and storm trysail heaving to, practice makes perfect—even when trying to stop, heaving to faqs.

The heaving to sailing maneuver is one that every skipper should be familiar with. It’s much handier than it might sound.

It’s roughly akin to coming to a stop in a powerboat and drifting. But the sails are still up, so the boat is much more stable than a powerboat would be. A better comparison might be a powerboat with stabilizers and can automatically hold a position relative to the waves for a comfortable ride.

Once hoveto, a boat makes little progress to windward or leeward—its motion stops to the point that its ground speed will be less than two knots or so. But one of the best things about heaving-to is that you can do it in a flash—meaning it’s a way to slam on the brakes and stop your forward movement if someone goes over or you need to fix something on board immediately.

Why else might you want to try heave to sailing? Here’s a list of times when skippers have found it helpful to heave to.

- To take a break from sailing for a while, maybe to get some sleep or make dinner when in heavy weather

- To wait outside a dangerous cut or inlet until dawn or a move favorable tide for entry

- To reduce pressures on the rig to make a repair

- To ease the motion on deck so as to make going forward safer or more comfortable

- To make it easier to put a reef in the mainsail

- To come to an immediate stop in order to retrieve an object or even recover a man overboard

- With reefed sails, to ride out a storm at sea

A Guide to Heaving To in Your Own Boat

Figuring out how to heave two in your boat isn’t very difficult, but it will take a little practice. Because each boat handles a little differently, has a different amount of windage and sail area, there can be no precise guide for the exact setup that will work best.

Instead of focusing on specifics, like speed or direction of drift, look to get the basics set up and then fine-tune the ride for your boat when heaving to .

Any kind of sailboat can be hove to. The technique works well for full-keel cruisers, fin-keel racers, catamarans, trimarans, cutters, or ketches–regardless of sail plan or sail size. But to figure out the best way to get your boat hove to, the best solution is to go out and practice!

It’s worth noting that you might want to plan which tack to take once you’re in the heave to position. If you take the starboard tack, you will have the right of way over other sailing vessels on the port tack. Even though you’ve stopped your forward movement, you are still technically considered to be sailing under way.

Basically, a heave to is begun by slowly tacking through the eye of the wind. But instead of allowing the windward sheet to run and letting the headsail swing across the bow, you keep the windward sheet made fast on the cleat.

The backwinded jib is the first step to getting the boat to stop. The headsail drives air over the main, so you are depriving the boat of all of that power by backwinding it.

Once the jib is backwinded, the boat’s bow will start falling off to downwind. Use the helm to keep the boat’s bow at about 45 to 60 degrees off the wind, sort of at a close haul angle.

The main sail may still be producing a little bit of lift at this point. The next step is to fine-tune that. It should be sheeted tightly for the tack, and now it’s a good time to let it out a little.

Keep in mind, though, that you don’t want the sail luffing. Luffing and flogging sails can be damaged easily, not to mention that the sound can really wear a sailor down. You want the sail to be right on the edge of producing what power it can with the jib backwinded. If the boat moves and the sail starts producing power, you want it to start to luff and fall off.

In the end, heaving to is a balance between the boat sailing and it not sailing. It may oscillate a bit, but any time it starts picking up speed or falling off to leeward, it should stop.

The final component in the equation is the rudder position. To keep the backed jib from making the boat fall off into a run, you will have had to turn the helm sharply to windward. In this setup, the sail pushed the boat one way, and the rudder counters it going the other.

Of course, the amount of rudder force will change as the boat slows down. So it’s most likely that you’ll leave the rudder locked at its stop. But you can tinker with it as necessary, especially if the boat is heading to irons or running the risk of tacking back on the original side.

When in doubt, tinker with the mainsail. Its trim and traveler position will have the most significant effects.

What to Expect when Hove To

So you’ve successfully hove to and figured out how to do it in your boat. You’ve tried several sail configurations, found the best hove to position, and just the right balance on the controls. Now what?

The benefits of heaving to might not be readily apparent until you’ve started cruising significant distances and embarking on multi-day passages. In coastal boating, the need to hove to seldom arises beyond getting some practice.

But on longer trips, crew fatigue becomes a much bigger problem. The sea state and strong winds often make a key part of that, as how the boat moving adds to the physically demanding nature of being out in heavy seas is hard to imagine without experiencing it a few times.

Heaving to is a great way to find the right balance of keeping the bow into oncoming waves in bad sea states while at the same time giving the crew a rest period.

Ready to move on? You can get out of the maneuver in one of two ways–either release the rudder and allow the boat to fall off on the new tack or sheet in the mainsail and go back on the original tack. The direction you pick will have to do with any other sailboats out there with you and how your boat handles in the conditions present.

Heaving To Modifications and Other Setups to Consider

Again, finding the correct setup to heave to successfully is all about trial and error. For it to work, you’re best off to go out in fairly calm conditions and see how it goes. Then practice every time you get a chance, progressively working up to understand how the boat handles in any condition.

One word of advice is not to take too much advice. Many people will tell you that such and such a boat won’t heave to, or that it won’t work. The more likely fact is that they just haven’t gone out and tried, or they tried once and didn’t know what to tinker with.

One of the most common complaints you’ll hear is that people have trouble getting catamarans to heave to. This is because catamarans have an incredible amount of windage on their topsides, which gives them more tendency to fall off to leeward sooner.

One technique is often described as parking a cat. This technique is like heaving to in a monohull , only the headsail is completely furled. Next, a heavily reefed mainsail is traveled all the way to leeward and sheeted hard in. Remember, the main is usually trimmed with the traveler and shaped with the sheet on cats. Finally, the rudders are turned hard to windward. The result should be a comfortable sideways drift at less than one knot.

Self-tacking headsails are great for short-handed sailing. Imagine tacking your boat without doing any winch work at all! If you short-tack up rivers or like to beat to windward often, a self-tacker is a miracle worker.

Self-tacking headsails have been around quite a while, although they are becoming more popular on recent models that feature fractional rigs with big mains. But if you look at the staysails on many cutters, you will notice that they are boom mounted on self-tending tracks. So if you can’t sheet the headsail in to backwind it, how can you heave to.

There are two methods you could employ, and which one you choose will depend on your boat and the conditions.

The first option is to rig a preventer to keep your headsail lashed on the windward side . This is an extra step, and it might be difficult if you want the ability to heave to at a moment’s notice. Rigging your preventer to the cockpit is one solution.

Another way is to forego the headsail altogether–furl it or drop it. Catamarans, fin-keel boats, and even some full-keel boats with cutaway forefoot can heave to just fine on a reefed mainsail alone.

Finally, sail selection will dramatically affect your heaving to success and technique. If you’re using heaving to as a storm tactic, don’t discount using it along with storm sails. A storm jib and storm trysail can be hove to like any other combination, although it is something you’d want to practice before trying it in stormy weather and rough conditions.

Every boat handles a little differently, and many skippers experience varying success with heaving to depending on the boat and the conditions. Start by practicing and getting a feel for how a hove to boat moves and remains stable. Then, expect to tinker with the setup a little to get it right.

Want to learn more about storm sailing, and practical boat handling in general? One of the best resources out there is the timeless classic by Lin and Larry Pardy, Storm Sailing Tactics.

- Add custom text here

Prices pulled from the Amazon Product Advertising API on:

Product prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.

What does it mean to hove to?

A sailboat that is hove to has stopped its forward progress but still has its sails up. Heaving to is a way of positioning the sails to counteract each other. A vessel that heaves to is stopped in the water yet still in a stable position to take on rough seas or storm conditions. Heaving to is a handy maneuver for skippers to know, whether used as a storm sailing tactic, to rescue a person in the water, to make a rigging repair, or as a simple way to stop for a snack or to cook something.

Should you heave to in a storm?

It depends on the storm, but it also depends on the boat and crew. Heaving to is a well-known storm tactic that reduces the boat’s motion and helps reduce fatigue and stress on both the crew and the vessel. A correctly set up vessel can lie hove-to for as long as it takes for the weather to pass, so long as there are no hazards as the vessel drifts slowly to leeward. In many instances, heaving to is preferable to other storm tactics available to a skipper, such as laying ahull, bearing off, using a sea anchor, or fore reaching.

Matt has been boating around Florida for over 25 years in everything from small powerboats to large cruising catamarans. He currently lives aboard a 38-foot Cabo Rico sailboat with his wife Lucy and adventure dog Chelsea. Together, they cruise between winters in The Bahamas and summers in the Chesapeake Bay.

- Find A School

- Certifications

- North U Sail Trim

- Inside Sailing with Peter Isler

- Docking Made Easy

- Study Quizzes

- Bite-sized Lessons

- Fun Quizzes

- Sailing Challenge

Heaving to – What is it and why you should know how to do it?

By: American Sailing Cruising Tips , Learn To Sail

ASA created a quiz a while back with one of the questions having to do with heaving to. Surprisingly, many people got the answer wrong, which led us to believe not everyone is out there heaving to! In fact, maybe they’re out there not even knowing what it means to heave to. So let’s go over it..

To heave to is to park the boat while out at sea. It’s mainly a heavy weather defense strategy but some people use the tactic to delay a harbor entrance for morning light, fix something or possibly just to have a little lunch at sea. As an example of how effective heaving to can be to endure through heavy weather, 26 sailors hove to in the infamous Fastnet Race where 18 people died in a horrific storm – none of those boats suffered any serious damage, let alone rolled or capsized.

Steps For Heaving To

- To lie on the tack opposite of the one you’re on, sheet the jib in tight, tack and leave the jibsheet cleated. As the boat passes through head to wind, the jib, held by the windward sheet, will set aback and push the bow downwind. Hold the mainsheet on the winch with its clutch open.

- Now steer the boat back toward the wind and make adjustments with the helm and the mainsheet until the boat is lying at a steady attitude to the wind on a close reaching heading. Normally, the wheel would be turned to windward. The mainsail might or might not need to be luffing.

Related Posts:

- Learn To Sail

- Mobile Apps

- Online Courses

- Upcoming Courses

- Sailor Resources

- ASA Log Book

- Bite Sized Lessons

- Knots Made Easy

- Catamaran Challenge

- Sailing Vacations

- Sailing Cruises

- Charter Resources

- International Proficiency Certificate

- Find A Charter

- All Articles

- Sailing Tips

- Sailing Terms

- Destinations

- Environmental

- Initiatives

- Instructor Resources

- Become An Instructor

- Become An ASA School

- Member / Instructor Login

- Affiliate Login

Attainable Adventure Cruising

The Offshore Voyaging Reference Site

As we have shared in earlier chapters in this Online Book, we now believe that for extreme weather, where large breaking waves may be present, a Series Drogue, as designed by Don Jordan, is the best survival strategy.

That said, on Morgan’s Cloud , heaving-to was for years our first and favourite strategy when the weather got nasty. And it has the particular benefit of being surprisingly comfortable. In fact, we have even enjoyed a sit-down dinner at the salon table when heaved–to in a full gale.

Also, heaving-to is not just for gales. The effort and expense we put in to making our boats heave-to well will be repaid in many other ways, including being able to take a pleasant rest from arduous conditions and being able to comfortably wait for daylight or better conditions before attempting a tricky landfall. It can also be an invaluable technique in the event that we must make a repair at sea.

Given all that, we have left our chapters on heaving-to in this Online Book.

Login to continue reading (scroll down)

Please Share a Link:

More Articles From Online Book: Heavy Weather Tactics:

- Introduction—We Need A System

- Goals For A Heavy Weather System

- Rogue Waves Are Not Bad Luck

- Just Get a Series Drogue Designed By Don Jordan…Dammit!

- Jordan Series Drogue Attachments And Launch System

- Alternatives to Chainplates For Drogue Attachment…Or Not

- Jordan Series Drogue Retrieval System

- Jordan Series Drogue Retrieval—An Alternative From Hal Roth

- Series Drogue Durability Problems

- Battle Testing a Jordan-Designed Series Drogue—Round 1

- Battle Testing a Jordan-Designed Series Drogue—Round 2

- Real Life Storm Survival Story

- Series Drogues: Learning From Tony Gooch

- Series Drogues: Learning From Randall Reeves

- Retrieval of Dyneema (Spectra) Series Drogues Solved

- When Heaving-To Is Dangerous

- Stopping Wave Strikes While Heaved-To

- Determining When Heaving-To Is Dangerous

- Transitioning From Heaved-to To a Series Drogue

- Storm Strategy—Fore-Reaching

- Surviving A Lee Shore

- Storm Survival Secret Weapon: Your Engine

- Storm Survival FAQ

- Companionway Integrity In A Storm

- Q&A: Safety of Large Pilothouse Windows

- Surviving Storms While Coastal Cruising—12 Strategy Tips

- Surviving Storms While Coastal Cruising—9 Tips for Anchorage and Harbour Selection

- Surviving Storms While Coastal Cruising—21 Preparation Tips

- Gale And Storm At Anchor Or On A Mooring Check List

- Summary And Conclusions For Heavy Weather Offshore Section

Myself and my partner used the tactic of heaving to in the North Atlantic and North Sea. The boat was a deep fin keel spade rudder 42 ft Beneteau . It was a pig to get it to stay in the heaved to position. It would go through the tack and go racing off under fully reefed, fully battoned main sail. If we cranked in the headsail and carefully handled the helm (wheel) it would eventually go -and stay- hoved to. We never used storm tri-sails or any other active tactic. The relief from broaching and surfing was immense. This was in 1995 on our way back from Svalbard via Jan Mayen, Iceland, Faroes and the Shetland Isles. I’m now 66 yrs old and have no intention of “nipping about the foredeck rigging tri-sales. The tactic worked in 10m sometimes 11m waves, So long as we stayed starboard or port bow quarter on we were ok. I’m off on the same trip in 2016 or 2017 by that time I’ll be heading towards 70 !! If Ben Shipton can hack it…. so can I . So it goes.

Apologies, I meant Ben Shepton.

Hi John. The comment above has just registered with me – “we retire below and maintain a watch………from the warm and dry chart table….” Do I see a contradiction here? On the proposed A40 this wouldn’t be an option. I must again ask if your views on the design aren’t too coloured by life on board Morgans Cloud. If even on your large and very well found yacht, the chart table is seen as a place where the on watch crew are able to do their job in bad weather, how much more important on a smaller boat? Although I suspect that the lack of a chart table on the A40 would not have a significant impact on initial sales, I suspec that it might well be the factor which prevents long term success for the design. Yours aye, Bill

There are several perfectly comfortable corners to rest in at sea on the A40 while keeping an eye on the instruments on the forward bulkhead (for those that wish to fit them).

If you can come up with a viable layout for the boat that does not sacrifice something important like the shower, U shaped galley, or push the salon too far forward or the cockpit too far aft, that includes a chart table of a useful size, I’m all ears.

Bottom line, you can’t have it all in an 18000 pound boat.

Perhaps we could give this argument a rest since we have been around the block on it at least three times. Time to agree to disagree I would suggest.

Hi John. OK I give in! 😉 I promise not to raise the topic again, unless I can come up with the magic answer you suggest. Liklihood? Probably zero. Yours aye, Bill

What to look for to determine that a yacht will heave to well.

If it is the preferred storm solution for the likes of Skip Novak, the Pardeys, Sir Peter Blake & Harries/Nickel then I reckon it is the preferred solution. Thanks for the very helpful advise on setting up a boat to heave-to. But what should we look for before purchasing or designing a boat to ensure it will respond and settle comfortably once correctly set up. I was very surprised to read “Like most modern yachts, Pèlerin doesn’t heave-to well”* I thought I might have seen a discussion on this in the Adventure 40 Hull & Keel section – perhaps it’s there and I missed it.

*https://www.morganscloud.com/2013/01/04/landfall-cape-verde-islands/

Generally moderate and heavy displacement longer keel hull forms heave-to better than lighter fin keel boats. That said, as I say in the post above, my thinking is that most any boat can be made to heave-to with the right gear. Read this chapter for a technique that helps with boats that tend to fore-reach out of their slick: https://www.morganscloud.com/2013/06/01/stopping-wave-strikes-while-heaved-to/

I would also add that despite my faith in heaving-to I would always want to carry a Jordan Series Drogue for serious offshore work and that goes double for lighter fin keeled boats and lifting keel boats.

I’m fully convinced Heaving-to is the best gale strategy in a monohull; but what about Catamarans? All the Heave-to material i have read assume mono boats! Cats are getting more popular and have limited underbodies to stabilize itself in the correct position.

Can you speculate on ways (sail plans + Gale riders) to make a Cat heave-to correctly?

I’m sorry, I just don’t know. I have sailed cats, but years ago, and not offshore. I’m guessing that it might be quite difficult, or even impossible, to get a cat to settle down and not move out of her slick, a requirement for safe heaving-to.

Given the lack of solid information on heaving-to in multihulls, I think that if placed in that situation, I would default to running off with a Jordan Series Drogue.

John If a Cat can’t be made to heave-to, then that is a solid reason for a person who desires to go long distance blue water cruising to choose a mono vs Cat! Their lives could depend on it. When people discuss the benefits of a Cat vs Mono, I don’t see this point brought up much.

I don’t think that I would say that the situation for cats was that bad. While I agree that heaving-to is a great option to have, the JSD is a proven survival technique, and I can’t see any reason that a cat could not use it.

I think, if it were me making the decision between cat and mono I would think more about the operator error tolerance of each type. Here I think there is a case in that even experienced cat crews can get caught with too much sail up and the result can be an inversion, whereas with a mono hull it would be “just” a knock down. Not saying that this disqualifies cats from offshore cruising, but rather it’s something to be realistic and think about.

While I personally prefer monohulls over cats I believe a JSD could even be of more benefit for a cat than for a monohull as the lever that keeps the boat stern-to the waves is a lot bigger with a cat than with a mono.

That’s a good point. That said, having read a lot about JSD usage and also all of Jordan’s theory papers several times, while it’s nice if the boat stays oriented directly down wind, I don’t think that it’s actually that important for roll over prevention. The key is that the load varies from almost nothing to huge on the JSD, so the boat will veer either side of directly down wind, but on the front face of a dangerous wave the JSD loads up quickly and pulls the boat straight.

The reason people don’t talk about heaving to with catamarans is that it just isn’t necessary. Cruising catamarans sail relatively flat and while they jerk back and forth and can have very hard wave strikes under the bridge deck it is nothing like the deep heel and large scale violent movements of a monohull. There is no need to heave to to be able to cook for example. And if the seas/wind are so strong that we need to radically slow down for comfort, at that point it is time to go to the JSD anyway.

Hi John, revisiting the JSD on a Cat idea. I assume you are using the JSD for running-off not heaving-to? Am i correct? I don’t like running off in a gale as my first strategy as i have to be 100% perfect for long periods with small crew + i remain inside the gale longer. Ugh.

Question: is there a chance one could use the Galerider off the bow to remain hove to better in a Cat? Having a reliable heave to strategy in a Cat is important. Are there any on this board that have used a hove-to Strategy on a Cat that could lend us their wisdom?? Thanks all!

Yes, running off only on the JSD. For heaving to I use a Galerider as detailed in a later chapter. As to whether that would work on a cat of not, I simply don’t know. This kind of thing can only be properly investigated by trying it in real offshore conditions.

I’m curious if you had a chance to see how the typically rigged Boréal would heave to, with its “spider web” mainsheet with no traveller and it’s self- tacking staysail. So far, we have found her to heave to quite well with the genoa back-winded, but I believe I would have to rig additional lines to back-wind the staysail, i.e. prevent it from tacking through.

I have only sailed a Boreal for a couple of hours in light air and smooth water, so I would defer to you on that one.

That said, if she heaves-to well with the genoa, I would think that it would be even better with the staysail since the centre of effort will be further aft helping to overcome any issues from not having a traveler.

And, when I was thinking of buying a Boreal, I did have a very quick look at the self tacking set up and concluded that it would be reasonable easy to rig a line to keep the staysail sheet traveler to windward, but I don’t remember the details of what I was thinking. How does that task look to you?

The other thought is, have you tried heaving-to with just the main and no headsail at all, with just the windage from the furled headsails keeping the bow from tacking through? Our boat does this fine once the wind gets over 30 and I’m thinking that, given the position of the keel box, maybe the Boreal would do the same with the board up. Might also be interesting to try just a little area down on one of the aft lea boards?

I have been a believer in heaving to in gales since, as a young man, I crewed for Bill Tilman. The technique will vary from boat to boat. Tilman’s pilot cutters hove to with a deep reefed mainsail and staysail, but I found that my 1930s gaff cutter was happy with the mainsail stowed and the boom in the rigid gallows, the roller jib rolled and the close reefed staysail set. I think that, as you point out, the windage of the furled sails came into it.

I now have a Nicholson 55 with a longish fin and Skegness rudder. To my surprise and delight these boats also heave to well with close reefed mainsail and reefed staysail.

In all the above cases – helm lashed about half down.

Home » Blog » Sail » Heave to – definition and how to do it

Heave to – definition and how to do it

By Author Fiona McGlynn

Posted on Last updated: August 18, 2023

Sailboats, unlike cars, don’t have the luxury of pulling over to the side of the road, whenever the driver needs a break. Fortunately, they can heave to, a simple technique for stopping a sailboat that is far more comfortable and controlled than just dropping the sails and drifting.

Over three years and 13,000 miles of blue water sailing, we hove to on many occasions. By adjusting the mainsail, headsail, and rudder, we were able to comfortably stall our boat for hours, even days, at a time. It’s a simple maneuver that we’ve found useful in many different situations—stopping the sailboat to make repairs, take a swim, or wait for daylight to enter a harbor.

Notes: this post contains some affiliate links. If you purchase through these links we’ll earn a small commission

Heave to definition and meaning

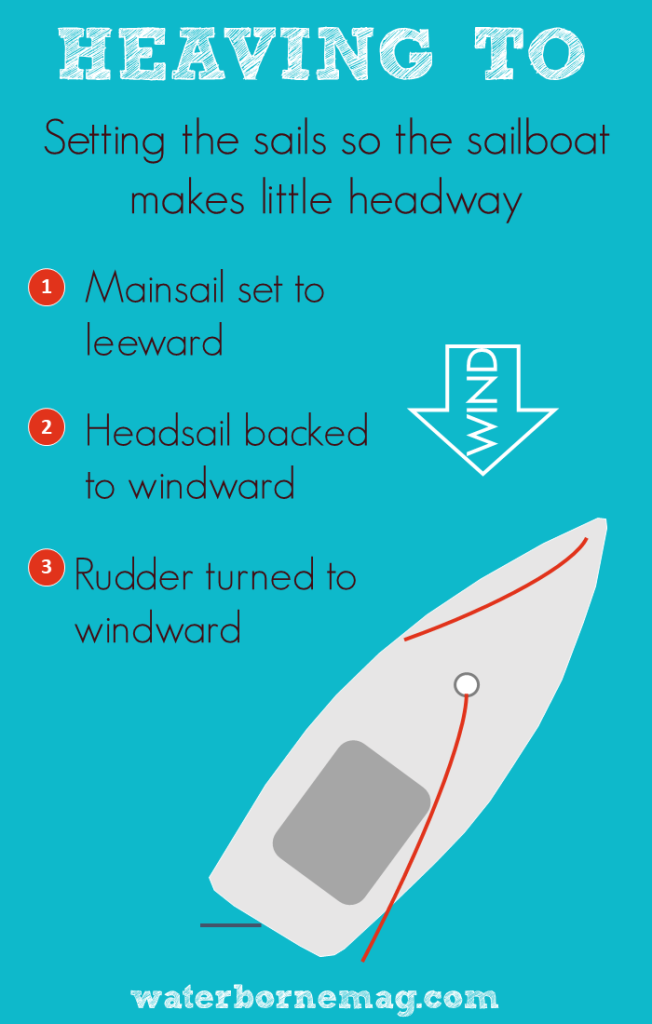

The 67th edition of Chapman Piloting & Seamanship defines heaving-to as “setting the sails so that a boat makes little headway, usually in a storm or a waiting situation.”

I would add that it’s a very useful technique in everyday sailing (e.g., making repairs, breaking for lunch), especially for short-handed and solo sailors.

How does it work?

Heaving to is accomplished by backing the headsail (i.e., sheeting it to the windward side). This counteracts the force of the main sail. The headsail pulls the bow to leeward, while the mainsail pushes the bow back to windward. This push and pull between the sails results in halting the boat’s forward progress.

Benefits of heaving-to

Stops forward progress

Heaving too is a controlled and comfortable way of staying relatively stationary.

Makes the boat more stable and comfortable

By staying at 40-50 degrees to the wind, with the bow taking the brunt of the waves, the boat becomes more stable.

Some also say that as the boat drifts downwind, the keel creates a slick of disturbed water which further dampens the effect of any breaking waves to windward.

Offers a quick getaway

If you need to move in a hurry, say to get out of the way of oncoming traffic, your sails are already up and ready to propel you forward. You can be back underway within seconds.

When to heave to

Here are some situations where you might find heaving to useful:

- Waiting for another boat . On a 26-day Pacific crossing, we hove to in order to wait for a disabled yacht so that we could accompany them for the rest of the passage.

- Waiting for daylight . Rather than risk entering a harbor with unknown hazards, we would often heave to and wait for daybreak.

- Freeing up hands from the helm . Heaving to is a helpful technique for short-handed or solo sailors who don’t have a self-steering wind vane or autopilot. While hove to, the person at the helm is freed up to do other tasks.

- Making repairs en route . We hove to when we needed to make repairs to our auto-pilot while during a multi-day passage. It was also helpful when we needed to stop so we could dive and inspect our rudder for damage.

- Having a coffee break or making lunch. Sometimes it’s just nice to take a break. The stability that comes with heaving to can make cooking a meal below decks a lot easier.

- Going for a swim. On hot days near the equator, we’d heave to and indulge in a quick dip (while tied in of course).

- Letting seasick crew rest. If your crew is struggling with seasickness, heaving to may offer them some respite.

- Heavy weather. While we’ve fortunately never needed to heave to on account of bad weather, we know sailors who have. One friend spent three days hove-to off in heavy seas and strong winds off the coast of Australia.

While heaving to can be very effective in heavy sea states, it’s important to recognize that there is no single storm tactic that is always going to be the right choice, regardless of the boat and conditions. In truly extreme weather, say a survival storm, you may also need to consider the use of a sea anchor, drogue, and more advanced techniques. For more on storm tactics, Storm Tactics: Modern Methods of Heaving-to for Survival in Extreme Conditions by Lin and Larry Pardey.

Can all sailboats heave to?

Some say that modern boats with fin keels don’t heave to as well as a full keel boat, but you should be able to heave to on most sailboats, including catamarans.

It is possible to inadvertently end up fore reaching while attempting to heave to, which may account for some confusion over whether your boat is properly hove to or not. We discuss forereaching in more detail at the end of this post.

How to heave to

The goal of heaving to is to balance the mainsail and a back-winded headsail so that they cancel each other out. When done properly, the boat stays at roughly a 40-50 degree angle to the wind and waves while making minimal headway.

Finding that balance is different on each boat. Your boat’s sail plan, displacement, keel type, and hull design will all affect how she heaves to. While most sources recommend aiming for 40-50 degree angle to the wind, there are boat types that might heave to anywhere from 30-60 degrees off the wind.

You’ll need to experiment with how you set your sails on your own boat to achieve the right combination.

As with any new skill, practice in good weather when the conditions are steady and well within your comfort zone.

1. Reef according to the conditions.

If you’re at full sail, your first step may be to reef both the headsail and mainsail appropriately for the conditions you’re sailing in. On our boat, this would have been full sail at 5 knots of wind and fully reefed at 25 knots.

Too much sail and you’ll risk being knocked down, too little sail and you won’t stay pointed in the right direction.

To reef the headsail this may mean furling your genoa, using a staysail, or even getting out your storm jib. In some cases, you may want to swap out your reefed mainsail for a trysail.

2. Sail close haul.

Sail close haul, ensuring your sails are tightly trimmed.

3. Slowly tack the boat without releasing the jib.

You should land on the new tack with a backed jib.

4. Steer the boat so it stays at a 40-50 degrees angle to the wind.

The backed headsail will cause the boat to head down past 60 degrees. Steer to compensate for this and keep the boat 40-50 degrees off the wind.

Feather the main as you work the boat back upwind. Take care if you approach 40 degrees – too much momentum will cause you to tack back again.

If the boat won’t round up, your headsail is overpowering your mainsail. You may need to reduce the head sail area to find the right balance.

If the boat wants to round up into wind and tack, your mainsail is overpowered. You could try easing the main slightly.

5. Turn the rudder to windward

Once you’re reached 40-50 degrees and you’ve bled off speed, turn the rudder all the way to windward (wheel to windward, tiller to leeward) and lock it off or lash it in place.

Watch to see what your boat does and if it stays in a relatively stable position, within 40 to 50 degrees. Don’t stress if the boat swings between 40 and 50 degrees. This is normal and is caused by the wind and waves. The boat should stay hove-to unless thrown off by a big wave or gust.

Getting out of heave to

When ready to get underway again, bring the rudder amidship and release the windward sheet, allowing the jib to flip to the other side. Trim your jib on the leeward side and once you’ve got some forward momentum you can head on your intended course.

Other tips for heaving to

Stay aware of your speed and course, and always maintain a good lookout . Though not underway, you can still drift into hazards or get into a collision. It’s a good idea to give yourself enough sea room (space) when heaving to.

If you’re in a busy area, heave to on a starboard tack (keep boom on the port side) to maintain the right of way over sailboats on a port tack.

Inspect your sails for chafe. When heaving to, your jib sheet or the clew of your genoa may sit and rub on the shrouds. If left unattended it will eventually wear through your sheet or sail.

You can prevent this by reefing the genoa , putting chaffing protection on the shrouds TK, or even re-running the sheet inside or between the shrouds.

Watch Skip Novak demonstrate how to heave to in this video

Fore reaching vs. heaving to

Fore reaching is an alternative to heaving-to in some situations. Unlike heaving-to which completely stalls the boat, leaving you drifting at 1-2 knots downwind, fore-reaching keeps a boat moving forward at 1-2 knots to windward.

It may involve sheeting the jib amidship (not backed) or lowering it entirely while keeping a reefed mainsail sheeted in tight and the helm kept slightly to leeward.

Fore reaching can be a useful technique when you want to continue to make headway but go much more slowly. Say, for instance, if you were heading into an outgoing tide of current but wanted to maintain your position.

Some think that fin-keeled boats are prone to unintentionally forereaching while attempting to heave-to. Unlike heaving-to, fore reaching does not provide the slick of calmed water on the windward side of the boat.

Heave to or hove to?

Heave to is a phrasal verb. In the present tense, you might say, “Let’s heave to and take a break for lunch.”

If the action is complete (past tense), you can use the past participle: hove to. For example, “The sailing ship hove-to for days off the coast of New Zealand.”

Fiona McGlynn is an award-winning boating writer who created Waterborne as a place to learn about living aboard and traveling the world by sailboat. She has written for boating magazines including BoatUS, SAIL, Cruising World, and Good Old Boat. She’s also a contributing editor at Good Old Boat and BoatUS Magazine. In 2017, Fiona and her husband completed a 3-year, 13,000-mile voyage from Vancouver to Mexico to Australia on their 35-foot sailboat.

Terms and Conditions - Privacy Policy

78 Old Fishermans Wharf

Monterey, CA 93940

10:00AM - 6:00PM

- (831) 372-7245

Info & Reservations

Keep Calm and Heave to

- Joe Bassani

- January 15, 2020

Table of Contents

Heave to some professional advice.

“Heaving to is not just a storm strategy, it’s also a vital seamanship skill.” – John Kretschmer, Sailing a Serious Ocean.

In my opinion, the best strategy for dealing with storms is to avoid them. If you are docked safely in your home port, stay there. If you are on a cruise, find a protected anchorage and button up to ride out the weather. Unfortunately, it’s not always possible to avoid storms. If you find yourself in storm seas, consider heaving-to as an option to safely weather the storm.

What is Heaving To?

Heaving-to is one of the first skills a keelboat sailor learns during her basic sailing instruction. It is a time-honored storm strategy that, along with more active techniques like forereaching and running off, is an important part of a sailor’s heavy weather “tool kit”.

Heaving-to is a simple maneuver that places the vessel in a balance of forces, allowing it to “fend for itself” while sailing slowly and under control. This allows the crew to take a break and conserve energy while waiting for the storm to pass.

How is it Done?

Photo taken from American Sailing Associations “Basic Coastal Cruising” textbook used for the ASA 103 course.

From a close haul, the helm should announce her intention to tack and heave-to. The crew signals readiness for the maneuver and the helmsman initiates turns through the wind to the new close-hauled heading. T he previously working jib sheet remains made off and the jib backs or fills with wind on the opposite side. In calm winds, the captain may wish to let the main sail out to stall; in heavy seas and high winds, it may be advisable to douse the mainsail.

Finally, turn the tiller to leeward or the wheel to windward so that the rudder is counteracting the force of the wind on the jib. Adjust the rudder as necessary to achieve the proper balance that will ensure the vessel travels slowly (1-2 knots) along the new close-hauled course with very little heel and noticeable leeward drift.

Several factors affect the ability of a vessel to heave-to, including amount of freeboard, keel type, sail size and wind speed. It is a good idea to practice heaving-to on your boat, in fair weather, to understand the design characteristics that are unique to your vessel and the optimal rudder and sail adjustments required for a stable heave-to. If at first you struggle to achieve a satisfying heave-to, don’t give up. Every boat is different, and practice is the key to success.

Why We Heave To

Heaving-to is a great storm strategy, but it is also a useful fair-weather technique for loitering or holding in a particular area without anchoring:

- When arriving at a destination at night and waiting until daylight to enter unfamiliar waters

- During repairs that require a steady ship

- While waiting to link up with other yachts for a flotilla or start of a race

- When the crew needs a break

Becoming proficient a heaving-to is an important skill that will make a keelboat sailor’s time on the water safer and definitely more enjoyable.

If you’d like to learn more about this or another sailing-related topic, visit us at Sail Monterey or call us at (831) 742-7245. The American Sailing Association has also written this great article about heaving to if you’d like to dive deeper into the manuever.

Share this post!

Consultation

- Sail Monterey Brochure

- Vessel Delivery

- Learn to Operate Your New Boat

- Pre-Purchase Vessel Inspections

- Travel Guide

- Meet Our Staff

- Other Activities

- Hotels Near Us

- Sailing School

- 78 Old Fishermans Wharf. Monterey, CA 93940

- Office Hours: 10a.m. – 6p.m.

- Catamaran Cruises

- Special Events

- Sailing Classes

Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Catamaran Sailing Techniques Part 6: Coping with heavy weather – with Nigel Irens

- Harriett Ferris

- November 10, 2015

Anticipating bad weather is, as in any boat, the best way to prepare for a blow, but if you’re caught out, Nigel Irens has some advice specific to cats

A racing boat that also has access to high-quality weather forecasting data should be able to steer clear of potentially dangerous weather by outrunning it. Performance cruisers with fine bows should be able to surf downwind in all but the most extreme weather, often travelling safely at speeds of 20 knots or more for periods of, say, 10-15 seconds.

But in the same conditions a stubbier, bluff-bowed charter catamaran would soon start feeling dangerous if the crew were pushing too hard under these conditions.

Obviously reducing sail is the first response, but as mentioned earlier in this series, shortening a mainsail in downwind conditions is not really possible without turning head to wind, and if the wind and sea-state are rising then the moment to do that safely may already have passed.

An experienced crew will have anticipated the rising wind and reefed the main a few hours back. Shortening sail forward of the mast is a piece of cake by comparison – especially if all it takes is to let the jib fly and roll up some of the area. Getting rid of an asymmetric might be challenging, but at least it won’t be dangerous.

Being caught with too much sail up along with the knowledge that you’ve missed the chance to round up and reef is not very helpful. You’ve inadvertently got into this situation and you’ve obviously still got to think up some way to get out of it.

Reefing the main

Brute force might provide the get-out-of-jail-free solution for reefing a main downwind in worsening conditions. But this might not be possible as the sail will not drop when you release the halyard because it will be pressing hard against the standing rigging. The luff cars will also be under load from the side (which they are not really designed to be).

If you have left it too late to head up safely, brute force may be the only way to get the main down

The best way forward is to leave the mainsail halyard where it is and sheet the main in until it is no longer pressing against the rigging. Some vang load on the boom will be needed because simply easing the sheet will invite the sail to twist so that it is still hard against the rigging.

The next move is to start loading both the luff and clew reef lines that are ready for hauling in the next reef. When they are bar-tight you can try easing a bit of halyard. If the sail moves that’s good news, but it will only fall a short way before the sail is once again draped over the standing rigging.

It’s only by repeating this process as many times as necessary that the exposed mainsail should end up the size you want it to be. It may be hard work, but who cares if you can feel the relief at getting out of this fix.

Rounding up to reef

If the mainsail still refuses to come down your only remaining option may be to round up. Given that conditions have likely worsened, this may not be very appealing, but careful preparation can help to minimise the stress.

First, ensure that the halyard is flaked and ready to go. You will need one person to focus on this job plus someone on the helm at all times as you cannot afford for the bows to fall away midway through the manoeuvre.

Also, make sure that the reef line(s) is ready to be hauled in, although if things have got this bad and you are expecting worse to come, it may be best simply to drop the mainsail and return to your downwind course as quickly as possible.

If turning upwind to reef, roll up the headsail by about two-thirds to stop it flogging and losing control

If you have a spare pair of hands, make sure someone is available to tail the mainsheet as you come into the breeze to prevent the sheet from flogging violently.

Then, if you can, have someone ready to pull the sail down at the luff. Full length battens on car sliders often mean that the mainsail luff forms tubes when it is lowered, which get inflated with the strong wind and prevent the sail from dropping on its own. The sail may need some help to get it down onto the boom. Make sure that the crewmember tasked with this is clipped on properly and braced ready for the round up into the breeze.

Have the leeward engine running – in neutral is fine – just so that you can give a burst of forward drive if required to keep your steerage and help with a quick bear away once the manoeuvre is complete.

Finally, communication is key. Make sure everyone knows exactly what you are doing and when they need to act. The quicker you can carry out the drop the better – it will be noisy when you head up into the breeze.

Planning for the conditions

It may be that reducing sail is in response to a short-lived squall, after which you’ll be able to make sail again, but if this is the beginning of a more serious blow then you need to have planned what to do as conditions worsen.

You could try sailing under bare poles for a while, but this can feel a little awkward as you may surf quite well down a wave then almost lose steerage way in the troughs, so setting a smidgin of jib will probably feel better as it’s no surprise that being pulled along from the front is more likely to improve steerability than simply being pushed by the wind pressure on the transoms and aft bulkhead.

Either way if the wind continues to rise a time might come when you want to forget about progressing and just render the boat safe while reducing the stress and anxiety of the crew by making things comfortable below.

You might want to remove all sails and proceed under engine

The usual way to achieve this is to set some kind of sea-anchor or drogue, which is designed to do just that, although advising on the right way to go about this is one of those subjects that offers huge scope for deeply entrenched disagreement.

Sea anchors and drogues

The term ‘sea-anchor’ usually refers to a device with an area big enough to hold the boat almost stationary – usually bows on to the seas – whereas a ‘drogue’ is a device intended to slow the boat’s drift downwind.

The consensus among catamaran sailors seems to be that setting a device from the stern works better than from the bow, so the drogue approach is the obvious choice as a full sea anchor tends to hold the sterns down, increasing the risk of taking a tonne of green water in the cockpit.

There are some neat series drogues available now which consist of a strong line with multiple tiny drogues attached to it. That means you effectively have variable power in the ‘braking system’ and can experiment until you get the best result.

Building some confidence in this sort of device through trial and error plays a vital role in preparing to manage real heavy weather. Feeling that you’re on top of this kind of situation also gives you peace of mind.

Staying safe upwind

Staying safe when going upwind is a lot less complicated. To start with if you’re on a standard charter-style catamaran you’d have to be trying pretty hard to get into any serious danger of capsizing.

Deck hardware may be undersized for the obvious reason that it’s a way to limit cost, but it’s also true that anything that makes it hard to power up one of these boats is going to help keep it right-side-up. In any event it soon becomes obvious (through trial and error) that hanging onto too much sail in a rising wind never pays, so reef early and don’t hesitate to press the engine into service.

As the wind rises, don’t put off reefing, shorted sail on the headsail first for control

Reefing is relatively easy upwind, but it’s important to keep the boat moving forward – maybe by keeping the headsail powered up – so you maintain steerage way. If you stop you might get knocked back by a big breaker and that could dig the sterns, which in extreme cases could even result in a stern-first capsize.