Why Do Catamarans Capsize? The Facts You Need To Know

Catamarans have become increasingly popular in recent years as a fun and safe way to explore the waters around you.

But what happens if a catamaran tips over? What are the causes and safety tips to avoid it? In this article, we’ll explore why catamarans are more prone to capsizing than other boats, what can cause them to capsize, and what you should do if your catamaran tips over.

We’ll also discuss what to do if your catamaran capsizes and how to right it if possible.

So, if you’re looking to stay safe while sailing your catamaran, this article is for you!

Table of Contents

Short Answer

Catamarans can capsize due to a variety of reasons, including strong winds, large waves, and imbalance.

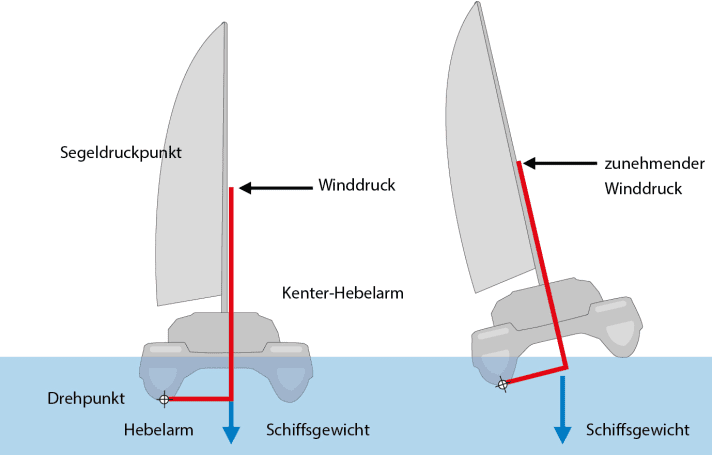

When a catamaran is caught in a gust of wind, the increased wind pressure on one side of the catamaran can cause it to lean to one side, which can lead to a capsize if not corrected.

Additionally, if the catamaran is not balanced properly, with too much weight on one side of the boat, it can easily capsize.

Lastly, large waves can easily cause the boat to roll, leading to a capsize.

The Design of Catamarans

Catamarans are two-hulled watercraft, which makes them inherently more susceptible to instability and capsize than more traditional vessels.

This is due to their wide-hulled design, which makes it easier for the boat to become unbalanced.

The two separate hulls also make them more difficult to steer, as the hulls act like two sails and can push the boat in unintended directions.

Additionally, catamarans have less buoyancy, making them more likely to capsize if they are overloaded with cargo.

The sails of a catamaran can also contribute to the likelihood of a capsize.

As the wind increases, the sails can act as a sail, pushing the boat over.

If the sails are not managed correctly, they can push the boat too far, resulting in a capsize.

Finally, large waves can cause a catamaran to become unstable and eventually capsize.

The wide-hulled design of catamarans makes them more vulnerable to waves, as the two hulls can move independently and cause the boat to become unbalanced.

Additionally, the asymmetrical shape of catamarans makes them more likely to flip over in high waves, as the force of the waves can push the boat in one direction and cause it to overturn.

Overall, catamarans are inherently more unstable than other types of vessels due to their wide-hulled design, and they can easily become unbalanced if improperly loaded with cargo.

Additionally, excessive wind can cause the sails of a catamaran to act as a sail, pushing it over and causing it to capsize.

Lastly, large waves can cause a catamaran to become unstable and eventually capsize.

For these reasons, it is important for catamaran owners to understand why catamarans can capsize and take the necessary precautions to prevent it.

Improper Loading Can Lead to Catamaran Capsizing

When it comes to catamarans, proper loading is key to staying afloat.

A catamaran is inherently more unstable than other types of vessels due to their wide-hulled design, and they can easily become unbalanced if improperly loaded with cargo.

This can cause the vessel to become unstable and eventually capsize.

To avoid this, it is important to ensure the catamaran is loaded correctly and that the weight is evenly distributed across the two hulls.

When loading a catamaran, it is important to consider the size, shape, and weight of the items being loaded.

It is also important to be aware of the catamarans overall weight capacity.

Overloading the vessel or having an unevenly distributed load can cause the catamaran to become off-balance, leading to dangerous and potentially life-threatening situations.

It is also important to be aware of the center of gravity when loading a catamaran.

Cargo should be distributed in such a way that the center of gravity remains low and the catamaran remains stable.

This will allow the vessel to handle waves and wind more effectively and reduce the risk of capsizing.

When loading a catamaran, it is important to be aware of the risks associated with improper loading.

Taking the time to properly load the vessel and ensure the weight is evenly distributed can help reduce the risk of capsizing and keep passengers and crew safe.

Wind Can Cause Catamarans to Capsize

When it comes to why catamarans capsize, strong winds are a major factor.

This is because catamarans are inherently more unstable than other types of vessels due to their wide-hulled design.

The wide hulls can act as sails, catching the wind and pushing the boat over.

This is especially true if the catamaran is not properly loaded, as excessive wind can quickly create an imbalance and cause it to capsize.

Additionally, strong winds can cause the sails of a catamaran to act as a sail, pushing it over and causing it to capsize.

This can be especially dangerous if the sails are not properly trimmed, as the wind can catch them and cause the catamaran to lose its balance.

Furthermore, if a catamaran is not equipped with good quality sails and rigging, they can easily break or tear in high winds, making it more difficult to control the vessel and leading to a possible capsize.

In order to prevent a catamaran from capsizing due to wind, it is important to always be aware of the current weather conditions and adjust the sails and rigging accordingly.

It is also important to make sure the catamaran is properly loaded and balanced, as an imbalance can quickly lead to capsize.

Finally, it is important to use quality sails and rigging, as they will be more resistant to strong winds and will help to keep the catamaran under control.

Large Waves Can Cause Catamarans to Capsize

When it comes to catamarans, large waves can be one of the main causes of capsizing.

This is due to the unique design of catamarans, which have two hulls connected by a platform.

This wide-hulled design gives catamarans more surface area than other types of vessels, making them inherently less stable.

While this can make them great for cruising in calm waters, it can also make them vulnerable to the effects of large waves.

When a large wave hits a catamaran, it can cause the vessel to become unbalanced.

This is because the wave can push one hull up while the other remains in the water.

This can create an imbalance in the catamarans center of gravity, causing it to become unstable and eventually capsize.

In addition to the effects of large waves, catamarans can also become unbalanced if they are improperly loaded with cargo.

As with any vessel, it is important to ensure that the catamaran is properly loaded so that it is not too top heavy.

If the vessel is carrying too much weight on one side, it can become unbalanced and be prone to capsizing.

Finally, excessive wind can also cause a catamaran to become unstable and eventually capsize.

Catamarans can act like a sail when the sails are open, and the wind can push the vessel over if it is not properly secured.

Its important to always make sure that the sails are properly secured and the catamaran is not exposed to excessive winds.

In conclusion, catamarans can capsize for a variety of reasons, such as strong winds, waves, and improper loading.

It is important to be aware of these potential dangers when operating a catamaran, and always take the necessary precautions to ensure the safety of the vessel and its occupants.

Safety Tips to Avoid Catamaran Capsizing

When it comes to owning and operating a catamaran, safety should always be your top priority.

While catamarans are inherently more unstable than other types of vessels, there are several steps you can take to help prevent your vessel from capsizing.

First, make sure your catamaran is properly loaded.

This means that the weight should be evenly distributed between the two hulls so as to maintain a balanced vessel.

Additionally, any heavy items should be secured in place to prevent them from shifting during travel.

Second, take caution when sailing in high winds or waves.

Catamarans are particularly vulnerable to strong winds and large waves, as the sails can act as a sail and push the vessel over.

If you are sailing in these conditions, make sure to keep the sails close-hauled and lower the mast to reduce wind resistance.

Additionally, try to stay away from large waves and steer into them instead of away to reduce the risk of capsizing.

Third, make sure all safety equipment is in working order.

This includes life jackets, flares, and other essential items that can be used in the event of an emergency.

Additionally, make sure that everyone on board is aware of the safety procedures and understands how to respond in case of a capsize.

By following these safety tips, you can help ensure that your catamaran remains upright and that everyone on board remains safe.

While capsizing can happen for a variety of reasons, it is important to take the necessary steps to prevent it from happening in the first place.

How to React if Your Catamaran Is Capsizing

If you find yourself in a situation where you think that your catamaran is capsizing, the most important thing to do is remain calm.

It is tempting to panic, but if you panic, you may make it harder to react in a way that can help save your vessel.

It is also important to remember that catamarans can capsize in a matter of seconds, so it is important to act quickly.

The first step you should take is to lower the sails and turn off the engine.

This will help reduce the wind pressure on the hull and the risk of the catamaran tipping over.

Next, make sure that everyone on board is wearing life jackets and has access to a floatation device.

If possible, move to the center of the boat, as this is the safest spot in case of a capsize.

If the catamaran begins to capsize, dont jump off the boat.

Instead, grab onto something solid to help keep your balance and wait for the boat to right itself.

If the boat doesnt right itself, assess the situation for any potential hazards such as rocks or logs that may be in the water.

If the boat is still in danger of capsizing, it is best to abandon ship and get to safety.

It is important to remember that catamarans can capsize in a matter of seconds, so being prepared and knowing what to do when it happens can help keep everyone safe.

It is also important to make sure that the catamaran is properly loaded, that its sail settings are appropriate for the wind conditions, and that everyone on board is wearing a life jacket in case of a capsize.

By following these tips, you can help ensure a safe and enjoyable outing on your catamaran.

Is It Possible To Right a Capsized Catamaran?

In most cases, it is possible to right a capsized catamaran.

However, the difficulty of the task depends on the size and shape of the vessel, as well as the conditions in which it capsized.

If the catamaran is small enough, it may be possible to right it by hand, but larger vessels may need to be righted with the help of a crane or other lifting device.

Additionally, the crew must take into account the weather conditions when attempting to right a capsized catamaran.

High winds can make the task more difficult, as they can push the vessel further away from the shore.

If the catamaran can be righted, the next step is to assess the damage and determine if the vessel can be safely sailed.

If the catamaran is severely damaged, the crew may need to abandon it or seek assistance from a towboat or other vessel.

If the damage is minor, the crew may be able to repair the vessel and continue sailing.

It is important to note that if a catamaran is righted, it is still vulnerable to capsizing again if it is not properly loaded or if the weather conditions are too severe.

Therefore, it is important for the crew to take all necessary precautions to ensure that the vessel is properly loaded and that the crew is aware of the conditions before continuing on their voyage.

Final Thoughts

It’s important to understand the risks associated with owning and operating a catamaran.

By taking the necessary precautions, such as proper loading, avoiding high winds and waves, and having the right safety equipment on board, you can ensure that your catamaran remains stable and you stay safe while on the water.

If you find yourself in a situation where your catamaran is capsizing, react quickly and take the proper steps to right the vessel.

With the right knowledge and preparation, you can enjoy your time on the water without worrying about a potential capsizing.

James Frami

At the age of 15, he and four other friends from his neighborhood constructed their first boat. He has been sailing for almost 30 years and has a wealth of knowledge that he wants to share with others.

Recent Posts

When Was Banana Boat Song Released? (HISTORICAL INSIGHTS)

The "Banana Boat Song" was released in 1956 by Harry Belafonte. This calypso-style song, also known as "Day-O," became a huge hit and remains popular to this day for its catchy tune and upbeat...

How to Make Banana Boat Smoothie King? (DELICIOUS RECIPE REVEALED)

To make a Banana Boat Smoothie King smoothie at home, start by gathering the ingredients: a ripe banana, peanut butter, chocolate protein powder, almond milk, and ice. Blend the banana, a scoop of...

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

Bristol Channel Cutter 28: Circumnavigator’s Choice

Hunter 35.5 Legend Used Boat Review

Pearson Rhodes 41/Rhodes Bounty II Used Sailboat Review

Hallberg-Rassy 42 Used Sailboat Review

Best Crimpers and Strippers for Fixing Marine Electrical Connectors

Thinking Through a Solar Power Installation

How Does the Gulf Stream Influence our Weather?

Can You Run a Marine Air-Conditioner on Battery Power?

Practical Sailor Classic: The Load on Your Rode

Anchor Rodes for Smaller Sailboats

Ground Tackle Inspection Tips

Shoe Goo II Excels for Quick Sail Repairs

Solutions for a Stinky Holding Tank

Diesel Performance Additives

What Oil Analysis Reveals About Your Engine

Hidden Maintenance Problems: Part 3 – Gremlins in the Electrics

Seepage or Flooding? How To Keep Water Out of the Boat

Painting a New Bootstripe Like a Pro

Alcohol Stoves— Swan Song or Rebirth?

Living Aboard with an Alcohol Stove

Choosing the Right Fuel for Your Alcohol Stove

Preparing Yourself for Solo Sailing

How to Select Crew for a Passage or Delivery

Preparing A Boat to Sail Solo

Re-sealing the Seams on Waterproof Fabrics

Waxing and Polishing Your Boat

Reducing Engine Room Noise

Tricks and Tips to Forming Do-it-yourself Rigging Terminals

Marine Toilet Maintenance Tips

Learning to Live with Plastic Boat Bits

- Sailboat Reviews

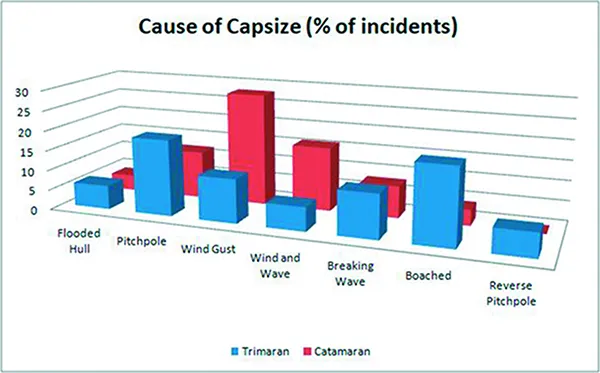

Multihull Capsize Risk Check

Waves, squalls, and inattention to trim and helm contribute to instability..

In recent years we’ve seen a surge in interest in multihulls. Thirty years ago, when my experience with cruising multihulls began, nearly all of the skippers served an apprenticeship with beach cats, learning their quirks by the seat of their pants. They hiked out on trapezes and flew head-over-heels past their pitch-pole prone Hobie 16s, until they learned the importance of keeping weight way aft on a reach and bearing off when the lee bow began to porpoise.

By contrast, the new generation of big cat buyers skipped this learning process, learning on monohulls or even choosing a big stable cat as their first boat. Heck, nobody even builds real beach cats anymore, only pumped up racing machines and rotomolded resort toys. So we’re guessing there are a few things these first-time cruising multihull sailors don’t know, even if they have sailed cruising cats before.

It is extremely hard to capsize a modern cruising cat. Either a basic disregard for seamanship or extreme weather is required. But no matter what the salesman tells you (“none of our boats have ever …”), it can happen. A strong gust with sail up or a breaking wave in a survival storm can do it. And when a multihull goes over, they don’t come back.

Trimarans tend to be more performance oriented than catamarans. In part, this is because it’s easier to design a folding trimaran, and as a result Farrier, Corsair, and Dragonfly trimarans had a disproportionate share of the market.

In spite of this and in spite of the fact that many are raced aggressively in windy conditions, capsizes are few, certainly fewer than in equivalent performance catamaran classes. But when they do go over, they do so in different ways.

Trimarans have greater beam than catamarans, making them considerably more resistant to capsize by wind alone, whether gusts or sustained wind. They heel sooner and more than catamaran, giving more warning that they are over powered.

Waves are a different matter. The amas are generally much finer, designed for low resistance when sailing deeply immersed to windward. As a result, trimarans are more susceptible to broach and capsize when broad reaching at high speed or when caught on the beam by a large breaking wave.

In the first case, the boat is sailing fast and overtaking waves. You surf down a nice steep one, into the backside of the next one, the ama buries up to the beam and the boat slows down. The apparent wind increases, the following wave lifts the transom, and the boat slews into a broach. If all sail is instantly eased, the boat will generally come back down, even from scary levels of heel, but not always.

In the second case a large wave breaks under the boat, pulling the leeward ama down and rolling the boat. Catamarans, on the other hand, are more likely to slide sideways when hit by a breaking wave, particularly if the keels are shallow (or raised in the case of daggerboards), because the hulls are too big to be forced under. They simply get dragged to leeward, alerting the crew that it is time to start bearing off the wind.

Another place the numbers leave us short is ama design. In the 70s and 80s, most catamarans were designed with considerable flare in the bow, like other boats of the period. This will keep the bow from burying, right? Nope. When a hull is skinny it can always be driven through a wave, and wide flare causes a rapid increase in drag once submerged, causing the boat to slow and possibly pitchpole.

Hobie Cat sailors know this well. More modern designs either eliminate or minimize this flare, making for more predictable behavior in rough conditions. A classic case is the evolution of Ian Farrier’s designs from bows that flare above the waterline to a wave-piercing shape with little flare, no deck flange, increased forward volume, and reduced rocker (see photos page 18). After more than two decades of designing multihulls, Farrier saw clear advantages of the new bow form. The F-22 is a little faster, but more importantly, it is less prone to broach or pitchpole, allowing it to be driven harder.

Beam and Stability

The stability index goes up with beam. Why isn’t more beam always better? Because as beam increases, a pitchpole off the wind becomes more likely, both under sail and under bare poles. (The optimum length-to-beam ratios is 1.7:1 – 2.2:1 for cats and 1.2:1-1.8:1 for trimarans.) Again, hull shape and buoyancy also play critical roles in averting a pitchpole, so beam alone shouldn’t be regarded as a determining factor.

Drogues and Chutes

While monohull sailors circle the globe without ever needing their drogues and sea anchors, multihulls are more likely to use them. In part, this is because strategies such as heaving to and lying a hull don’t work for multihulls. Moderate beam seas cause an uncomfortable snap-roll, and sailing or laying ahull in a multihull is poor seamanship in beam seas.

Fortunately, drogues work better with multihulls. The boats are lighter, reducing loads. They rise over the waves, like a raft. Dangerous surfing, and the risk of pitchpole and broach that comes with it, is eliminated. There’s no deep keel to trip over to the side and the broad beam increases the lever arm, reducing yawing to a bare minimum.

Speed-limiting drogues are often used by delivery skippers simply to ease the motion and take some work off the autopilot. By keeping her head down, a wind-only capsize becomes extremely unlikely, and rolling stops, making for an easy ride. A properly sized drogue will keep her moving at 4-6 knots, but will not allow surfing, and by extension, pitch poling.

For more information on speed limiting drogues, see “ How Much Drag is a Drogue? ” PS , September 2016.

Capsize Case Studies

Knock wood, we’ve never capsized a cruising multihull (beach cat—plenty of times), but we have pushed them to the edge of the envelope, watched bows bury, and flown multi-ton hulls to see just how the boat liked it and how fast she would go. We’re going to tell you about these experiences and what can be learned from them, so you don’t have to try it.

First, it helps to examine a few examples of some big multihull capsizes.

Techtronics 35 catamaran, John Shuttleworth design

This dramatic pitchpole occurred in a strong breeze some 30 years ago. In order to combine both great speed and reasonable accommodation, the designer incorporated considerable flare just above the waterline, resulting in hulls that were skinny and efficient in most conditions, but wide when driven under water in steep chop.

The boat was sailing fast near Nova Scotia, regularly overtaking waves. The bows plowed into a backside of a particularly steep wave, the submerged drag was huge, and the boat stopped on a dime. At the same time, the apparent wind went from about 15 knots into the high 20s, tripling the force on the sails and rapidly lifting the stern over the bow. Some crew were injured, but they all survived.

PDQ 32 Catamaran

On July 4, 2010, the boat’s new owners had scheduled time to deliver their new-to-them boat up the northern California coast. A strong gale was predicted, but against all advice, they left anyway. The boat turned sideways to the confused seas and a breaking wave on the beam capsized the boat. There were no injuries, and the boat was recovered with only moderate damage a few weeks later. Repaired, she is still sailing.

Another PDQ 32 was capsized in the Virgin Islands when a solo sailor went below to tend to something and sailed out of the lee of the island and into a reinforced trade wind.

Sustaining speed with wider tacking angles will help overcome leeway.

Cruising cats can’t go to windward. That’s the rumor, and there’s a kernel of truth to it. Most lack deep keels or dagger boards and ex-charter cats are tragically under canvassed for lighter wind areas, a nod to near universal lack of multihull experience among charter skippers. Gotta keep them safe. But there are a few tricks that make the worst pig passable and the better cats downright weatherly. Those of you that learned your craft racing Hobies and Prindles know most of this stuff, but for the rest of you cruising cat sailors, there’s some stuff the owner’s manual leaves out.

“Tune” the Mast

Having no backstay means that the forestay cannot be kept tight unless you want to turn your boat into a banana and over stress the cap shrouds. Although the spreaders are swept back, they are designed primarily for side force with just a bit of pull on the forestay. The real forestay tension comes from mainsheet tension.

Why is it so important to keep the forestay stay tight? Leeward sag forces cloth into the luff of the genoa, making it fuller and blunting the entry into the wind. The draft moves aft, the slot is pinched, and aerodynamic drag increases. Even worse, leeway (sideslip) increases, further increasing drag and sliding you away from your destination. Sailing a cruising cat to windward is about fine tuning the lift to drag ratio, not just finding more power.

How do you avoid easing the mainsheet in strong winds? First, ease the traveler instead. To avoid pinching the slot, keep the main outhaul tight to flatten the lower portion of the main. Use a smaller jib or roll up some genoa; overlap closes the slot. Reef if need be; it is better to keep a smaller mainsail tight than to drag a loose mainsail upwind, with the resultant loose forestay and clogged slot. You will see monos with the main twisted off in a blow. Ignore them, they are not cruising cats. It is also physically much easier to play the traveler than the main sheet. Be glad you have a wide one.

Check Sheeting Angles

Very likely you do not have enough keel area to support large headsails. As a result, you don’t want the tight genoa lead angles of a deep keeled monohull. All you’ll do is sail sideways. Too loose, on the other hand, and you can’t point. In general, 7-10 degrees is discussed for monos that want to pinch up to 40 degrees true, but 14-16 degrees makes more sense for cruising cats that will sail at no less than 50 degrees true. Rig up some temporary barber haulers and experiment. Then install a permanent Barber-hauler; see “ Try a Barber Hauler for Better Sail Trim ,” Practical Sailor , September 2019.

The result will be slightly wider tacking angles, perhaps 105 degrees including leeway, but this will be faster for you. You don’t have the same hull speed limit, so let that work for you. Just don’t get tempted off onto a reach; you need to steer with the jib not far from luffing.

Watch the fore/aft lead position as well. You want the jib to twist off to match the main. Typically it should be right on the spreaders, but that depends on the spreaders. If you have aft swept shrouds, you may need to roll up a little genoa, to 110% max.

Use your Tell-Tales

On the jib there can be tell-tale ribbons all over, but on the main the only ones that count are on the leech. Keep all but the top one streaming aft. Telltales on the body of sail are confused by either mast turbulence (windward side) or pasted down by jib flow (leeward side) and won’t tell you much. But if the leach telltales suck around to leeward you are over sheeted.

Keep Your Bottom Clean

It’s not just about speed, it’s also pointing angle. Anything that robs speed also makes you go sideways, since with less flow over the foil there will be less lift. Flow over the foils themselves will be turbulent. Nothing slows you down like a dirty bottom.

Reef Wisdom

Push hard, but reef when you need to. You will have the greatest lift vs. windage ratio when you are driving hard. That said, it’s smart to reef most cruising cats well before they lift a hull to avoid overloading the keels. If you are feathering in the lulls or allowing sails to twist off, it’s time to reef.

Don’t Pinch

Pinching (pointing to high) doesn’t work for cats. Get them moving, let the helm get a little lighter (the result of good flow over the rudder and keel), and then head up until the feeling begins to falter. How do you know when it’s right? Experiment with tacking angles (GPS not compass, because you want to include leeway in your figuring) and speed until the pair feel optimized. With a genoa and full main trimmed in well, inside tracks and modified keels, and relatively smooth water, our test PDQ can tack through 100 degrees with the boat on autopilot. Hand steering can do a little better, though it’s not actually faster to windward. If we reef or use the self-tacking jib, that might open up to 110-115 degrees, depending on wave conditions. Reefing the main works better than rolling up jib.

Boats with daggerboards or centerboards. The comments about keeping a tight forestay and importance of a clean bottom are universal. But the reduction in leeway will allow you to point up a little higher, as high as monohulls if you want to. But if you point as high as you can, you won’t go any faster than similar monohulls, and quite probably slower. As a general rule, tacking through less than 90 degrees, even though possible, is not the best strategy. A slightly wider angle, such as 100 degrees, will give a big jump in boat speed with very little leeway.

Chris White Custom 57

In November 2016, winds had been blowing 25-30 knots in stormy conditions about 400 miles north of the Dominican Republic. The main had two reefs in, and the boat was reaching under control at moderate speed when a microburst hit, causing the boat to capsize on its beam. There were no serious injuries.

Another Chris White 57 capsized on July 31, 2010. It had been blowing 18-20 knots and the main had a single reef. The autopilot steered. The wind jumped to 62 knots in a squall and changed direction so quickly that no autopilot could be expected to correct in time.

Gemini 105mC

In 2018, the 34-foot catamaran was sailing in the Gulf of Mexico under full sail at about 6 knots in a 10-15 knot breeze. Squalls had been reported on the VHF. The crew could see a squall line, and decided to run for cover. Before they could get the sails down, the gust front hit, the wind shifted 180 degrees, and the boat quickly went over.

38-foot Roger Simpson Design

The catamaran Ramtha was hit head-on by the infamous Queen’s Birthday storm in 1994. The mainsail was blown out, and steering was lost. Lacking any control the crew was taken off the boat, and the boat was recovered basically unharmed 2 weeks later. A Catalac catamaran caught in the same storm trailed a drogue and came through unharmed. Of the eight vessels that called for help, two were multihulls. Twenty-one sailors were rescued, three aboard the monohull Quartermaster were lost at sea.

15 meter Marsaudon Ts

Hallucine capsized off Portugal on November 11 of this year. This is a high performance cat, in the same general category as the familiar Gunboat series. It was well reefed and the winds were only 16-20 knots. According to crew, it struck a submerged object, and the sudden deceleration caused the boat to capsize.

Multihulls We’ve Sailed

Clearly seamanship is a factor in all of our the previous examples. The watch needs to be vigilant and active. Keeping up any sail during squally weather can be risky. Even in the generally benign tropics, nature quickly can whip up a fury. But it is also true that design choices can impact risk of capsize. Let’s see what the numbers can tell us, and what requires a deeper look.

Stiletto Catamaran

We’ve experienced a number of capsizes both racing and while driving hard in these popular 23-foot catamarans. The combination of light displacement and full bow sections make pitchpoling unlikely, and the result is very high speed potential when broad reaching. Unfortunately, a narrow beam, light weight, and powerful rig result in a low stability factor. The potential for capsize is real when too much sail is up and apparent wind is directly on the beam. The boat can lift a hull in 12 knots true. This makes for exciting sailing when you bring your A-game, but limits the boat to coastal sailing.

Corsair F-24 MK I trimaran

Small and well canvased, these boats can capsize if driven hard (which they often are), but they are broad beamed, short-masted, and designed for windy sailing areas. F-24s are slower off wind than the Stiletto, in part because of greater weight and reduced sail area, but also because the main hull has more rocker and does not plane as well. They are faster to weather and point considerably higher than a Stiletto (90-degree tacking angle vs. 110 degrees). This is the result of greater beam, a more efficient centerboard design, and slender amas that are easily driven in displacement mode. The boat is quite forgiving if reefed.

Going purely by the numbers, this boat seems nearly identical to the F-24. In practice, they sail quite differently. The Dash uses a dagger board instead of centerboard, which is both more hydrodynamic and faster, but more vulnerable to damage if grounded at high speed.

The rotating mast adds power that is not reflected in the numbers. The bridgedeck clearance is higher above the waterline, reducing water drag from wave strikes. The wave-piercing amas create greater stability up wind and off the wind. The result is a boat that is slightly faster than the original F-24 and can be driven much harder off the wind without fear of pitchpole or broach.

Without proper testing, calculating stability yields only a rough picture.

Evaluating multihull performance based on design numbers is a bit more complicated than it is with ballasted, displacement monohulls, whose speed is generally limited by hull form. [Editor’s note: The formula for Performance Index, PI has been updated from the one that originally appeared in the February 2021 issue of Practical Sailor.

The following definitions of units apply to the adjacent table:

SA = sail area in square feet

D (displacement) = weight in pounds

LWL = length of waterline in feet

HCOE = height of sail center of effort above the waterline in feet

B = beam in feet

BCL = beam at the centerline of the hulls in feet.

Since a multihull pivots around the centerline beam, the overall beam is off the point and is not used in formulas. Calculate by subtracting the individual hull beam from the overall beam.

SD ratio = SA/(D/64)^0.66

This ratio gives a measure of relative speed potential on flat water for monohulls, but it doesn’t really work for multihulls.

Bruce number = (SA)^0.5/(D)^0.333

Basically this is the SD ratio for multihulls, it gives a better fit.

Performance index = (SA/HCOE)^0.5 x (D/1000)^0.166

By including the height of the COE and displacement, this ratio reflects the ability of the boat to use that power to sail fast, but it understates the importance of stability to the cruiser.

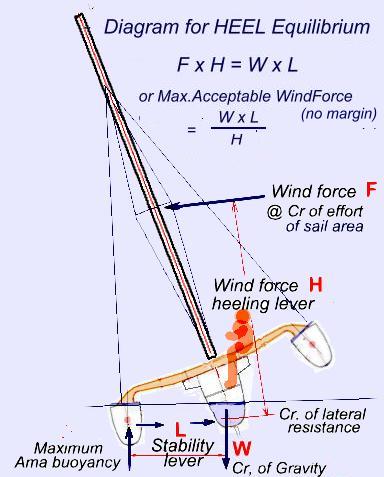

Stability factor = 9.8*((0.5*BCL*D)/(SA*HCOE))^0.5

This approximates the wind strength in knots required to lift a hull and includes a 40% gust factor. In the adjacent data sheet, we compare the formula’s predicted stability to observed behavior. Based on our experience on the boats represented, the results are roughly accurate.

Ama buoyancy = expressed as a % of total displacement.

Look for ama buoyancy greater than 150% of displacement, and 200 is better. Some early trimaran designs had less than 100 percent buoyancy and would capsize well before flying the center hull. They exhibited high submerged drag when pressed hard and were prone to capsize in breaking waves.

Modern tris have ama buoyancy between 150 and 200 percent of displacement and can fly the center hull, though even racing boats try to keep the center hull still touching. In addition, as a trimaran heels, the downward pressure of wind on the sail increases, increasing the risk of capsize. The initial heel on a trimaran is more than it is on catamarans, and all of that downward force pushes the ama even deeper in the water. Thus, like monohulls, it usually makes sense to keep heel moderate.

These numbers can only be used to predict the rough characteristics of a boat and must be supplemented by experience.

This is the first real cruising multihull in our lineup. A few have capsized. One was the result of the skipper pushing too hard in very gusty conditions with no one on watch. The other occurred when a crew unfamiliar with the boat ignored local wisdom and set sail into near gale conditions.

Although the speed potential of the PDQ 32 and the F-24 are very similar, and the stability index is not very different, the feel in rough conditions is more stable, the result of much greater weight and fuller hull sections.

Like most cruising cats, the PDQs hulls are relatively full in order to provide accommodation space, and as a result, driving them under is difficult. The increased weight slows the motion and damps the impact of gusts. Yes, you can fly a hull in about 25 knots apparent wind (we proved this during testing on flat water with steady winds), and she’ll go 8-9 knots to weather doing it, but this is not something you should ever do with a cruising cat.

Stability by the Numbers

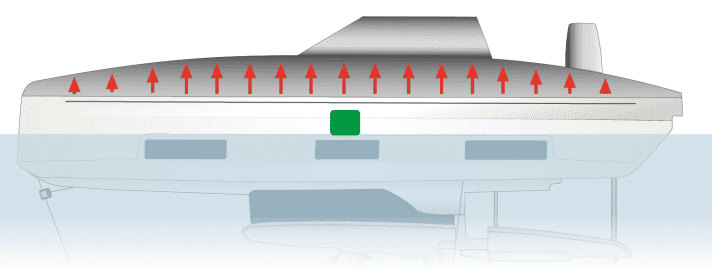

The “stability factor” in the table above (row 14) is based on flatwater conditions, and ignores two additional factors. Unlike monohulls, the wind will press on the underside of the bridgedeck of a multihull once it passes about 25 degrees of heel, pushing it up and over. This can happen quite suddenly when the boat flies off a wave and the underside is suddenly exposed to wind blowing up the slope of the wave. A breaking wave also adds rotational momentum, pitching the windward hull upwards.

Multihulls by the Numbers

Autopilot is a common thread in many capsizes. The gust “came out of no place…” No it didn’t. A beach cat sailor never trusts gusty winds. The autopilot should be disengaged windspeeds and a constant sheet watch is mandatory when gusts reach 30-40 percent of those required to fly a hull, and even sooner if there are tall clouds in the neighborhood. Reef early if a helm watch is too much trouble.

“But surely the sails will blow first, before the boat can capsize?” That would be an expensive lesson, but more to the point, history tells us that well-built sails won’t blow.

“Surely the rig will fail before I can lift a hull?” Again, that could only be the result of appallingly poor design, since a rig that weak will not last offshore and could not be depended on in a storm. Furthermore, good seamanship requires that you be able to put the full power of the rig to work if beating off a lee shore becomes necessary.

Keeping both hulls in the water is up to you. Fortunately, under bare poles and on relatively flat water even smaller cruising cats can take 70 knots on the beam without lifting … but we don’t set out to test that theory, because once it blows for a while over even 40 knots, the real risk is waves.

Everything critical to safety in a blow we learned on beach cats. Like riding a bike, or—better yet—riding a bike off-road, there are lessons learned the hard way, and those lessons stay learned. If you’ve been launched into a pitchpole a few times, the feeling you get just before things go wrong becomes ingrained.

Perhaps you are of a mature age and believe you monohull skills are more than enough to see you through. If you never sail aggressively or get caught in serious weather, you’re probably right.

However, if there’s a cruising cat in your future, a season spent dialing in a beach cat will be time well spent. Certainly, such experience should be a prerequisite for anyone buying a performance multihull. The statement might be a little pointed, but it just makes sense.

Capsize by Wind Alone

Capsizing by wind alone is uncommon on cruising multihulls. Occasionally a performance boat will go over in squally weather. The crew could easily have reefed down or gone to bare poles, but they clung to the idea that they are a sail boat, and a big cat feels so stable under sail—right up until a hull lifts.

Because a multihull cannot risk a knockdown (since that is a capsize), if a squall line is tall and dark, the smart multihull sailors drops all sail. Yes, you could feather up wind, but if the wind shifts suddenly, as gusts often do, the boat may not turn fast enough. Off the wind, few multihulls that can take a violent microburst and not risk a pitchpole. When a squall threatens, why risk a torn sail for a few moments of fast sailing?

You can’t go by angle of heel alone because of wave action. Cat instability begins with the position of the windward hull. Is it flying off waves?

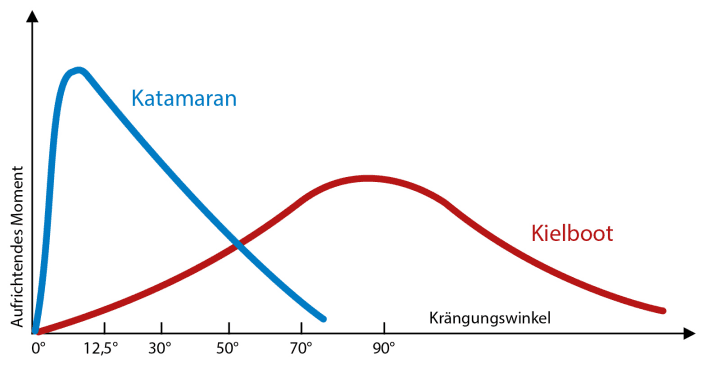

A trimaran’s telltale is submersion of leeward ama. Is the leeward ama more than 30-40 percent under water? The maximum righting angles is a 12-15 degrees for cats and 25-30 degrees for trimarans, but that is on flat water. Once the weather is up, observation of motion becomes far more important. Is the boat falling into a deep trough, or is at about to launch off a steep wave and fly?

Just as monohulls can surprise a new sailor by rounding up and broaching in a breeze, multihulls have a few odd habits that only present themselves just before things go wrong. Excuse the repetition, but the best way to learn to instinctively recognize these signs is by sailing small multihulls.

Sailing Windward

Because of the great beam, instead of developing weather helm as they begin to fly a hull, multihulls can suddenly develop lee helm, causing the boat to bear away and power up at the worst possible moment. This is because the center of drag moves to the lee hull, while the center of drive remains in the center, causing the boat to bear away.

If the boat is a trimaran, with only a center rudder, this rounding up occurs just as steering goes away. This video of a MOD 70 capsize shows how subtle the early warning signs can be ( www.youtube.com/watch?v=CI2iIY61Lc8 ).

Sailing Downwind

Off the wind, the effect can be the reverse. The lee hull begins to bury, and you decide it is time to bear off, but the submerged lee bow acts like a forward rudder. It moves the center of effort far forward and prevents any turn to leeward. Nearly all trimarans will do this, because the amas are so fine. The solution is to bear away early, before the ama buries—or better yet, to reef.

Conclusions

We’re not trying to scare you off multi-hulls. Far from it. As you can probably tell, I am truly addicted. Modern designs have well-established reputation seaworthiness.

But multihull seaworthiness and seamanship are different from monohulls, and some of those differences are only apparent when you press the boat very hard, harder than will ever experience in normal weather and outside of hard racing. These subtle differences have caught experienced sailors by surprise, especially if their prior experience involved only monohulls or cruising multihulls that were never pressed to the limit.

Although the numbers only tell part of the story, pay attention to a boat’s stability index. You really don’t want an offshore cruising boat that needs to be reefed below 22-25 knots apparent. Faster boats can be enjoyable, but they require earlier reefing and a more active sailing style.

When squalls threaten or the waves get big, take the appropriate actions and take them early, understanding that things happen faster. And don’t forget: knockdowns are not recoverable. It is satisfying to have a boat that has a liferaft-like stability, as long as you understand how to use it.

Technical Editor Drew Frye is the author of “Rigging Modern Anchors.” He blogs at www.blogspot/sail-delmarva.com

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

22 comments.

It’s interesting to read the report of the Multihull Symposium (Toronto, 1976) regarding the issues of multihull capsize in the formative years of commercial multihull design. There were so many theories based around hull shape, wing shape, submersible or non submersibe floats, sail area and maximum load carrying rules. My father, Nobby Clarke, of the very successful UK firm Cox Marine, fought many a battle in the early Sixties with the yachting establishment regarding the safety of trimarans, and I am glad that in this modern world technolgy answers the questions rather than the surmises of some establishment yachting magazines of the time.

Thank You Mr.Nicholson and Thank You to Practical Sailor for this great read superbly shared by Mr.Nicholson God bless you and our great Sailing Family.

Great read! Multi hulls are great party vessels which is why companies like Moorings and Sunsail have larger and larger numbers in their fleets. More and more multihulls are joining the offshore sailing fleets. Dismasting and capsizes do happen. Compared to mono hulls I know of no comparative statistics but off shore and bluewater, give me a mono hull. That is probably because I took one around with zero stability issues and only minor rig few issues. Slowly though; ten years.

Great read! Multi hulls are great party vessels which is why companies like Moorings and Sunsail have larger and larger numbers in their fleets. More and more multihulls are joining the offshore sailing fleets. Dismasting and capsizes do happen. Compared to mono hulls I know of no comparative statistics but off shore and bluewater, give me a mono hull. That is probably because I took one around with zero stability issues and only minor rig issues. Slowly though; ten years.

What’s an ama? Those who are new to sailing or even veteran sailors who have never been exposed to a lot of the terms simply get lost in an article with too many of those terms. I would suggest putting definitions in parentheses after an unfamiliar term to promote better understanding.

Vaka is the central, main hull, in a trimaran.

Ama is the “pontoon” hull at the end of the aka, or “crossbeam”, on each side of a trimaran.

I’m a geek, and therefore live in a dang *ocean* of the Jargonian & Acronese languages, and agree with you:

presuming 100% of audience is understanding each Jargonian term, and each Acronese term, is pushing credulity…

( and how in the hell “composition” means completely different things in object-oriented languages as compared with Haskell?? Bah. : )

As I understand it: Cats have an advantage in big beam seas because they will straddle a steep wave whereas a Tri can have its main hull on the wave crest with the windward ama’s bottom very high off the water and acting as another sail. Also, rig loads on a mono hull are calculated to be 2.5-3x the righting moment at a 45 deg heal; the reason being at 45 degrees the boat will still be making headway and feeling the dynamic loads in the seaway but beyond 45 degrees is a knockdown condition without seaway shock loads. A multihull rig on the other-hand can experience very high dynamic shock loads that are too short in duration to raise a hull.

Though I agree with much of the article content, the statement: “… this is because strategies such as heaving to and lying a hull don’t work for multihulls.” does not ring true in my experience. I have sailed about 70,000nm on cruising catamarans, a Canadian built Manta 38 (1992, 39ft x 21ft) with fixed keels and my present boat, a Walter Greene Evenkeel 38 (1997, 38ft x 19ft 6″) with daggerboards. I came from a monohull background, having circumnavigated the world and other international sailing (60,000nm) on a mono before purchasing the Manta cat. I owned that catamaran for 16 years and full time cruised for seven of those years, including crossing the Arctic Circle north of Iceland and rounding Cape Horn. I usually keep sailing until the wind is over 40knots, then the first tactic is to heave-to, and have lain hove-to for up to three days with the boat lying comfortably, pointing at about 50 to 60degrees from the wind and fore-reaching and side-slipping at about 1.5 to 2knots. Usually once hove-to I wait until the wind has reduced to 20knots or less before getting underway again. Lying ahull also works, though I have only used that in high winds without big breaking waves, as in the South Atlantic in the lee of South America with strong westerlies. I have lain to a parachute sea anchor and it is very comfortable, though lots of work handling all that gear and retrieving it and was glad to have deployed it when I did. I heave-to first, then deploy the sea anchor from the windward bow while in the hove-to position. The daggerboard cat will also heave-to well, though takes some adjusting of the boards to get her to lay just right, though I have not experience being at sea on this boat in as high of winds as with the Manta (over 60 knots). Catamaran bows have lots of windage and have little depth of hull forward. Thus you need mostly mainsail and little jib to keep her pointing into the wind. I aim for the wind to blow diagonally across the boat, with a line from the lee transom to the windward bow pointing into the wind as an optimum angle. As per taking the boat off autopilot when the wind gets near 20 knots is just not practical. The longest passage I have made on my catamarans has been from Fortaleza, Brazil, to Bermuda, nearly 3,000nm and across the squall prone doldrums and horse latitudes, taking 20 days. The autopilot steered the whole distance. I have never lifted a hull nor felt the boat was out of control despite having sailed in some of the most dangerous waters of the world.

I believe that your Techtronics 35 should be Tektron 35 (Shuttleworth) and as far as I know the capsize that occurred off Nova Scotia was, in fact, a Tektron 50 (Neptune’s Car I believe) sailed by the Canadian builder Eugene Tekatch and was reported as being off PEI. This capsize was well documented under a thread in “Steamradio” that I can no longer find. It appears that Steamradio is now, unfortunately, no longer operating. The report of the capsize was along the lines of the boat being sailed off wind with all sail in a gale. I think Shuttleworth indicated that they would have been doing about 30 knots. They then hit standing waves off PEI, the boat came to a standstill and with the change in apparent wind to the beam, over they went. Reading between the lines, Shuttleworth was pretty unhappy that one of his designs had been capsized in this manner, unhappier yet that some of the findings of I believe an american committee/ board were that the design was somehow at fault. Given Shuttleworth’s rep it seems unlikely. As I say these are recollections only.

Shortly afterwards Neptune’s Car was up for sale for a steal price.

I think Jim Brown (Trimaran Jim) when speaking of the Tektron 50 referred to it as weighing less than similarly sized blocks of Styrofoam. Admittedly, blocks of solid foam weigh more than one might imagine, but still a vivid point. Though Tektron 50 was light, we have far more options to build lighter boats today, than in the past.

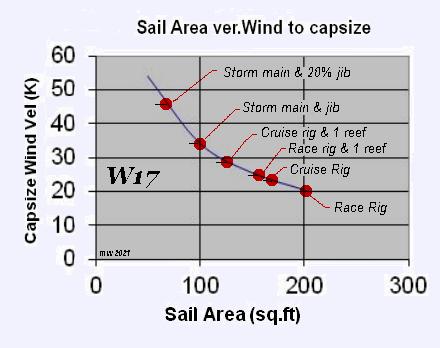

Good that Practical Sailor is looking at this issue and I agree with much of it, so thanks PS for that. Also fun to see Nobby Clark’s son chip in …. I met Nobby at the ’76 World Symposium in Toronto, when I was just starting to get interested in Trimarans. I have since owned 4 and as a naval architect, builder and sailor, now specialize in their design and ‘all things related’, with a quasi-encyclopedic website at: http://www.smalltridesign.com . So as a trimaran guru, I’d like to add a few things here. In my experience (now 45 years with multis) there is really too much difference between catamarans and trimarans to compare them on the basis of the same formulas. For example, lifting a hull on a cat brings about a major reduction in reserve stability ….. lifting an ama on a trimaran, certainly does not. Using 30-40% immersion of an ama is hardly a guide to limit or prevent a capsize on a trimaran as that’s not even close to normal operating immersion . I would recommend a reduction of ama bow freeboard to about 1-2% of the boat length (depending on a few size factors) is a better guide as the ‘time to really ease up’. This visual indicator is great on my boats but is very hard to judge on hulls with reverse bows where there is no deck up forward. For a number of reasons, I am against this shape but as I’ve already made my case on line about this, I’ll not repeat it here. Over 80% of the capsizes we see on line, show that mainsails were never released .. and that includes the capsize of the MOD70 in the YouTube referenced in the PS article. As several trimaran owners I deal with have also capsized or near-capsized their boats (particularly those between 22 and 40ft that ‘feel’ more stable than they really are, I am developing a few models of EMRs to help solve their issue, (EMR=Emergency Mainsheet Release) and these will be operated wirelessly by punching a large button under the skippers vest, as I am not in favor of any fully automatic release. This HAS to be a skippers decision in my opinion for numerous reasons. The first two units of this EMR dubbed ‘Thump’R, will be installed this Spring … one in Europe and the other in Australia, but one day, perhaps Practical Sailor will get to see and test one for you 😉 In a few words, my advice to all multihull sailors is to be very aware of the way your stability works on your specific boat and sail accordingly. We learn this instinctively with small beach boats, but is harder to ‘sense’ as boats get heavier and larger. I have sailed cats from a 60ft Greene cat to a 12ft trimaran and although some basics apply they are of course very different. But you still need to ‘learn the early signs’ of your boat, as these must be your guide. IMHO a good multihull design will be fairly light and easily driven which means that it will still sail well with less sail. This means that the use of a storm mainsail in potentially high wind can add much reserve stability and safety to your voyage. To give an example from my small W17 design that sets a rotating wingmast, the boats top speed to date is 15kts with 200 sqft, but with the storm mainsail and a partly-furled jib I can get the area down under 100sqft without losing rig efficiency. In fact, the tall narrow storm main with a 5.5:1 aspect ratio is now even MORE efficient as the wingmast is now doing a higher percentage of the work. In 25-30t storm conditions, I have now sailed 8kts upwind and 14.4kts down, and feel very dry and comfortable doing so … even at 80+. So get the right sails, and change down to small more efficient ones when it pipes up. A multihull storm sail should look nothing like a mono’s trysail … with our narrow hulls, we are sailing in a very different way. Happy sailing Mike

In the old days, low displacement, short and narrowly spaced amas were the design of choice. One was supposed to back off when they started to submerge. It was a visual indicator. Modern amas are huge. If a 24 foot tri like the Tremolino could be designed to use Hobie 16 hulls in the 70s, today it would carry Tornado hulls. The slippery shape of designs catches the eye, and their supposed less grabby when submerged decks, but these amas also carry 1.5-2x main hull displacement. The chance of burying them is significantly reduced.

The original intent of these slippery ama designs was to shake off wind. Though low drag shapes for reducing pitch pole risk are a consideration, it should be balanced against maintaining ama deck walkability. This is important in allowing one to service the boat or rig drogues or anchors, not to mention to position live ballast. I am thinking here of the smaller club and light crusing tris. You aren’t going to be able to do a lot of these things on monster luxury boats that are a different scale entirely. But they mater on the kinds of boat most people are likely to own.

Poring over tri design books, one will notice that the silhouette of, say, a 40 foot tri, and the smaller 20 foot design are very similar This yields a doubling of the power to weight ratio on the smaller boat. This difference can even be greater as the smaller boats are often nothing more than empty shells, yet may carry higher performance rig features like rotating masts. Smaller tris are often handicapped by the requirements of being folded for trailering which both limits beam and ama displacement, though it may tend to increase weight. On top of that, mainsail efficiency is much higher, these days, with squared shapes, and less yielding frabrics. And, of course, much larger sail plans. All the better, just so long as people realize what they have by the tail.

Excellent article…thank you!!!!!!!!!

Good article. One thing that concerns me about modern cruising cat is how far above water level the boom is. I first noticed this looking at Catana 47’s for hire in New Caledonia and recently saw large Leopards 48 & 50 footers visiting Fremantle Sailing Club, here in Australia, and in all cases the boom seems to be at least 20 feet (6 metres) above the water. This seems to greatly increase the heeling moment and reduce the amount of wind required to capsize the vessel. Mind you at 20+ tons, the weight of the Leopards probably makes them a bit more resistant to capsize. But why does the rig need to be so far off the water?

Notice to Moderator After having read this article a couple or days back, I emailed naval architect mike waters, author of the specialist website SmallTriDesign to read the article and perhaps comment. Nearly a day ago, he emailed me back to say that he had, yet there’s been nothing posted from him and now I see a post with todays date. With his extensive knowledge and experience I would have thought his insight to be valuable to your readers and I was certainly looking forward to seeing his input. What happened?

Yes, PS .. what’s cookin ? Thought readers would be interested to know that capsize control help maybe on the way 😉

Yes PS, what’s cookin’ ? Thought your readers would like to know that some anti-capsize help maybe on the way 😉

Great article! I’ve read it twice so far. Recently in Tampa Bay I sailed my Dragonfly 28 in 25 knots breeze and found that speed was increased (drag reduced?) after I put in one reef in the main. I think I should have reefed the Genoa first?

Absolutely Tim. Slim hulls, as for most trimarans and the finer, lighter catamarans will often sail more efficiently with less sail .., especially if with a rotating mast, and you can indeed get proportionally better performance. The boat sails more upright for one thing, giving more sail drive from improved lift/drag and less hull resistance .. and its certainly safer and more comfortable and can also be drier, as an upright boat tends to keep wavetops passing underneath more effectively. Even my W17 design has been shown to achieve over 90% of its top speed with only 1/2 the sail area, by switching to a more efficient, high-aspect ratio ‘storm mainsail’ set behind its rotating wingmast …, a far cry from a monohulls storm trysail in terms of upwind efficiency. Yes, wind speed was higher, but the boat sailed far easier and its definitely something that slim hulled multihulls should explore more, as they will then also be less likely to capsize. More here if interested http://www.smalltridesign.com

Darrell, is there some reason for blocking replies that hold opinions contrary to those of PS ? I am still hoping to read the expertise of those who actually study design and sail multihulls. The written target of PS is to accurately present facts and that implies the input of experts. Over the last 10 years, I have come to appreciate a few experts in the field of multihulls and right now, I see at least one of them is not being given a voice here. Your article made a lot of fine points but there are some issues needing to be addressed if PS it to remain a trusted source for accurate information. First, I have been told by a reliable source, you need to separate trimarans from catamarans and use different criteria to compare their stability as they do not respond the same and neither can you judge their reserve stability in the same way. I would also like to know what NA Mike Waters was hinting at when he said “capsize control help may be on the way” .. would you know anything about that? If not, then please invite or allow him space or the promise of PS fact-finding accuracy is heading down the drain for me. thanks

As a new subscriber to PS, it is a little disquieting to see no response to the two comments above by Tom Hampton.

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

C&C 40: What You Should Know | Boat Review

A Simple Solution for Boat Toilet Stink

An Italian Go Fast Sailboat – The Viko S 35 |...

What Is The Best Folding Bike For Your Sailboat?

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

Can a Catamaran Capsize? The Surprising Answer

Capsizing often happens with small boats like canoes, kayaks, and sailboats. But even for bigger boats like catamarans, which have an established reputation for stability and safety, it's still normal to wonder if they can capsize too. To give you peace of mind and prepare you for the worst, let's answer that question in this article.

A catamaran can capsize under extreme conditions, just like any other boat. Even the most stable catamaran can capsize if it's hit by a large wave, caught in a sudden gust of wind, or if the rotational force has overcome the stability of the boat. However, it's not something that happens frequently.

It can be a scary experience if a catamaran capsized, but you have to stay calm and know that most modern catamarans are designed to self-right. This means that they can turn themselves back over after capsizing. Let's continue reading to know what else can we do to recover from a catamaran capsize.

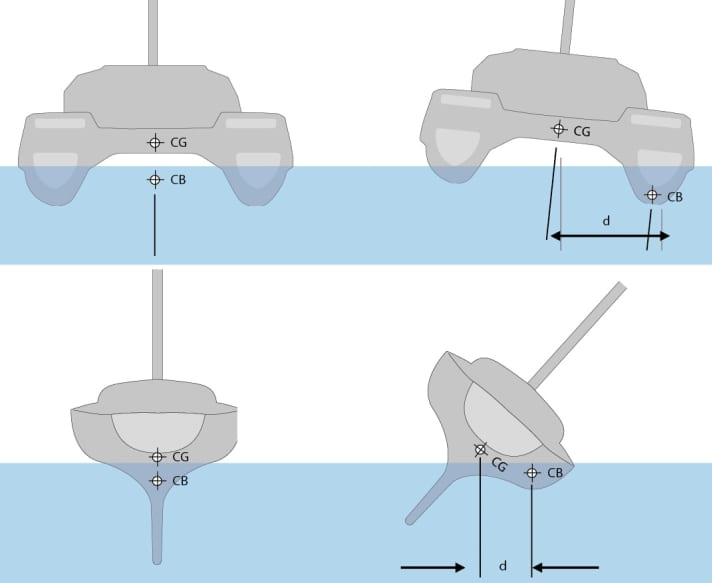

- A catamaran's stability is attributed to its center of gravity, its freeboard, and its pendulum-like behavior. However, despite its stability and speed, a catamaran can still capsize due to strong winds and capsizing waves.

- There are factors that can contribute to the likelihood of a capsize happening, such as wind speed, wave height, weather conditions, breaking waves, and the overall sailing conditions.

- The best thing to do to quickly recover from a capsize is to stay calm and position the boat to make it self-right quickly.

On this page:

A catamaran can capsize despite its stability, factors influencing catamaran capsizing, safety measures to prevent capsizing, recovering from a capsized catamaran.

A catamaran can capsize. However, it's not very common, and most catamarans are designed to be stable and safe in a variety of conditions.

Despite their stability and speed, catamarans can still capsize under certain conditions. Strong winds, large waves, and imbalance can all cause a catamaran to capsize. When a catamaran is caught in a gust of wind, the increased wind pressure on one side of the catamaran can cause it to lean to one side, which can lead to a capsize if not corrected.

Any boat can technically capsize , but there are specific factors that can contribute to a catamaran capsizing. One of the main reasons for catamaran capsizing is the effect of rotational forces. When these forces overcome the stability of the boat, it can lead to capsizing.

A catamaran is a type of multihull boat that has two parallel hulls connected by a deck or bridge. They are well known for their stability and speed, making them a popular choice for sailors and boaters.

One of the key advantages of their twin hulls is that it gives them a larger base and makes them less likely to tip over . It also helps to distribute the weight of the boat more evenly, providing greater stability. This is especially helpful in rough seas , where the catamaran's stability can help keep you safe and comfortable. Below are factors that contribute to the stability of catamarans:

Their center of gravity makes them stable

In a catamaran, the center of gravity is typically lower than in a monohull, which helps reduce the likelihood of capsizing. This is because the lower the center of gravity, the more stable the boat will be.

The freeboard also adds up to their stability

Their freeboard of a catamaran is typically lower than a monohull's, which helps to reduce the windage and the chances of the boat being pushed over by strong winds.

Their pendulum-like behavior helps them to be stabilized

When they encounter waves, the two hulls move independently of each other, which helps to reduce the rolling motion of the boat. This is because the weight of the boat is distributed between the two hulls, which act like pendulums, swinging in opposite directions to counterbalance the motion of the waves.

Aside from stability, another advantage of a catamaran is its speed. Because they have two hulls, they create less drag than a single hull and can move through the water more quickly and efficiently. This can be especially useful if you're trying to get somewhere quickly or if you're racing.

The height of the wave can affect the chance of capsizing

Wave height is a significant factor when it comes to catamaran capsizing. The higher the waves, the greater the risk of capsizing. This is because the waves can exert a significant amount of force on the boat, causing it to tip over.

Wave capsize occurs when a boat overtakes a wave and sinks its bow into the next one, causing it to capsize. However, this is also not very common and can usually be avoided by keeping an eye on the waves and adjusting your speed and course accordingly.

Wind speed is another important factor to consider

The stronger the wind, the more likely it is that a catamaran will capsize. The wind can create a lot of pressure on the sails, which can cause the boat to lean to one side and potentially capsize. To know more about the ideal wind speed in sailing, read this article.

Weather conditions can also play a role in catamaran capsizing

If there is a storm or other severe weather conditions, the risk of capsizing is much higher. Perhaps consider checking the weather forecast before setting out on a catamaran to ensure that conditions are safe. You may also try reading this article on the possible danger of sailing through thunderstorms.

Breaking waves can cause a catamaran to capsize

When waves break, they release a significant amount of energy, which can cause the boat to capsize. Try to keep an eye out for breaking waves and avoid them if possible.

The overall sailing condition can increase the likelihood of capsizing

You may need to be aware of the conditions and take appropriate precautions to ensure that you stay safe while on the water.

1. Ensure proper weight distribution

To prevent capsizing, you could check if the weight on your catamaran is evenly distributed, with heavier items stored low and towards the center of the boat. Try to avoid overloading your catamaran with too much weight.

2. Learn the right way of reefing

Reefing is the process of reducing the size of your sails to adjust to changing wind conditions. When the wind starts to pick up, you will need to reef your sails to prevent your catamaran from heeling over too much. You must learn how to reef your sails properly before you set out on your journey.

3. Know how to properly anchor and use the right anchor

An anchor can help keep your catamaran in place and prevent it from drifting in strong currents or winds. You need to know how to properly anchor your catamaran and always use an anchor that is appropriate for the size of your boat. Learn different anchoring techniques in tough conditions through this article: Boat Anchoring Techniques Explained (Illustrated Guide)

4. Utilize your catamaran's engine

Your engine can be a valuable tool for preventing capsizing. If you find yourself in a dangerous situation, such as strong winds or currents, you can use your engine to help keep your catamaran stable and prevent it from capsizing.

5. Use your boat tools to prevent it from capsizing

Keels, daggerboards, and centerboards all help stabilize your catamaran and prevent capsizing. You may need to check if these are properly installed and maintained.

6. Use the drogue to slow down the boat

A drogue is a device that can help slow down your catamaran and prevent it from capsizing in heavy seas. You can check if you have a drogue on board and learn how to properly use it in case you need to.

7. Make sure to have safety equipment onboard

Always make sure you have the proper safety equipment on board, including life jackets, flares, and a first aid kit. Everyone on board must also know where the safety equipment is located and how to use it.

8. Use an autopilot

Autopilot can help keep your catamaran stable and prevent it from heeling over too much. Consider learning how to properly use your autopilot before you set out on your journey.

Capsizing a catamaran can be a scary experience, but with proper preparation and practice, you can easily handle it. When the boat flips upside down, all the loose gear in the boat floats away (or sinks), and you are left with a capsized boat. Here are some steps that can help you recover from a catamaran capsize:

The first thing to do when your catamaran capsizes is to remain calm. Take a deep breath and assess the situation. Check if everyone on board is safe and accounted for.

Position the catamaran to self-right

Catamarans are designed to self-right, which means that they can turn themselves back over after capsizing. To self-right, the boat needs to be positioned in a certain way, usually with the mast pointing downwind.

Help the catamaran to self-right using the righting lines

If your catamaran doesn't self-right, you can help it by using the righting lines. These lines are attached to the bottom of the hulls, and they can be used to pull the boat back upright.

The buoyancy of the catamaran can help you recover

Catamarans are designed to be buoyant , which means that they can float even when they are upside down. This makes it easier to recover from a capsize.

Be prepared

The best way to prepare for a capsize is to practice recovering from one. Set aside some time to practice capsizing your catamaran in a controlled environment, like a calm lake. This will help you build confidence and prepare you for the real thing.

Leave a comment

You may also like, catamaran vs monohull in rough seas: which is better.

Catamarans and monohulls have different designs that affect how they handle rough sea conditions. In fact, they have an advantage over each other when sailing in …

Are Catamarans Safer than Monohulls? - Not Always

The Perfect Size Catamaran to Sail Around the World

What is the Ideal Wind Speed for Sailing?

The Illustrated Guide To Boat Hull Types (11 Examples)

Own your first boat within a year on any budget.

A sailboat doesn't have to be expensive if you know what you're doing. If you want to learn how to make your sailing dream reality within a year, leave your email and I'll send you free updates . I don't like spam - I will only send helpful content.

Ready to Own Your First Boat?

Just tell us the best email address to send your tips to:

Catamaran Capsize: What to Do When Your Boat Flips

by Emma Sullivan | Aug 10, 2023 | Sailing Adventures

Short answer catamaran capsize:

A catamaran capsize refers to the overturning or tipping over of a catamaran, a type of multihull boat with two parallel hulls. This can occur due to various factors such as strong winds, improper handling, or technical failures. Capsize prevention measures like proper training, ballasting systems, and stability considerations are crucial for safe navigation and reducing the risk of catamaran capsizing incidents.

Understanding Catamaran Capsizing: Causes, Risks, and Prevention

Catamarans are a popular choice among sailing enthusiasts due to their sleek design, stability, and impressive speed. However, even the most experienced sailors can fall victim to catamaran capsizing if they fail to understand the causes, risks involved, and how to prevent mishaps. In this blog post, we will delve into the intricacies of understanding catamaran capsizing to ensure that you can enjoy your sailing adventures with peace of mind.

Causes of Catamaran Capsizing:

1. Overloading: One common cause of catamaran capsizing is overloading. Exceeding the weight limitations of your vessel can lead to instability and loss of control in rough waters. It is essential to understand your catamaran’s maximum carrying capacity and distribute weight evenly throughout the boat.

2. High Winds: Strong gusts can swiftly overpower a catamaran, making it prone to capsizing. Understanding weather patterns and keeping a close eye on wind forecasts becomes crucial before embarking on any sailing journey.

3. Wave Interference: Waves play an integral role in causing catamaran capsizing accidents. Large waves hitting the boat at unfavorable angles can destabilize it or even cause it to pitchpole (the front end dives into a wave while flipping). Studying wave behaviors and having knowledge of proper sailing techniques when encountering such conditions is vital for preventing mishaps.

Risks Involved in Catamaran Capsizing:

1. Injury or Loss of Life: The most significant risk associated with catamaran capsizing is potential injury or loss of life. Falling from a capsized vessel into rough waters poses serious dangers, especially if rescue or self-recovery measures are not promptly executed.

2. Damage to Property: Struggling against strong currents after a capsize can cause considerable damage to both your vessel and other boating equipment on board. Repairs can be costly, and the loss of personal belongings can be emotionally distressing.

3. Environmental Impact: Capsized catamarans may spill fuel, oil, or other hazardous substances into the environment, causing pollution and harm to marine life. Understanding the potential environmental impact of a capsizing event highlights the importance of responsible boating practices.

Preventing Catamaran Capsizing:

1. Proper Training and Education: Acquiring formal training courses in sailing, especially ones specifically focusing on operating a catamaran, is essential for preventing capsizing accidents. Learning about safety procedures, navigation techniques, and understanding your vessel’s capabilities will significantly reduce risks.

2. Maintenance and Inspection: Regularly inspecting your catamaran for any signs of wear or damage can help identify potential issues that could lead to a capsize. Maintaining sails, rigging, and hull integrity ensures that your vessel is in optimal condition for safe sailing .

3. Weather Monitoring: Stay updated with meteorological reports and observe weather patterns carefully before setting sail . Avoid venturing out during severe weather conditions such as high winds or thunderstorms to minimize the risk of capsizing incidents.

4. Weight Distribution: Pay close attention to how weight is distributed within your catamaran to maintain its stability . Ensuring an even distribution across both hulls reduces the risk of capsizing due to imbalance.

5. Safety Equipment: Always have suitable safety equipment readily available onboard your catamaran in case of emergencies. This includes personal flotation devices (PFDs), flares, whistles, safety lines, fire extinguishers, and distress signals – which are all vital tools for rescuers spotting you quickly during a capsize situation.

By thoroughly understanding the causes behind catamaran capsizing incidents along with their associated risks while implementing preventative measures explained above; you can minimize the likelihood of encountering such mishaps on your sailing adventures.”

Remember that maintaining vigilance at all times during your sailing trips is crucial , regardless of your experience level. Stay informed, respect the power of nature, and prioritize safety to ensure a memorable and enjoyable catamaran experience for yourself and everyone on board.

How to React When a Catamaran Capsizes: Step-by-Step Guide

Title: Successfully Navigating a Catamaran Capsizing: A Comprehensive Step-by-Step Guide

Introduction: Catamarans are undoubtedly marvelous vessels, designed to provide both stability and speed on the water . However, even the most experienced sailors may find themselves in a situation where their catamaran capsizes unexpectedly. To help you stay prepared and confident, we have crafted a detailed step-by-step guide on how to react when faced with such an unfortunate event. From staying calm to implementing effective techniques, this guide will equip you with the necessary knowledge to swiftly recover from a catamaran capsizing.

Step 1: Maintain Composure In any crisis situation, keeping calm is key. Take a deep breath, clear your mind and remind yourself that panic only exacerbates the challenge at hand. Remaining composed allows you to think rationally and make wise decisions during each subsequent step.

Step 2: Assess the Situation Upon realizing that your catamaran has capsized, take a moment to evaluate the circumstances around you. Determine whether any crew members or passengers require immediate assistance or medical attention. Prioritizing safety should always be your primary concern.

Step 3: Activate Floatation Devices Ensure that everyone onboard has access to personal floatation devices (PFDs). Encourage everyone to put them on without delay – these will significantly enhance everyone’s chances of staying buoyant while awaiting rescue.

Step 4: Conserve Energy Capsizing can be physically demanding; therefore, it is crucial for everyone involved to conserve energy during this challenging time. Remind crew members and passengers not to exert themselves unnecessarily and advise them on using slow movements in order not to tip over or destabilize the boat further.

Step 5: Establish Communication Locate any communication devices available onboard, such as handheld radios or emergency flares . If possible, make contact with nearby vessels or coastguards immediately for assistance. Modern technologies like personal locator beacons (PLBs) can effectively alert authorities to your location, ensuring swift and targeted rescue efforts.