- Sails & Canvas

- Hull & Structure

- Maintenance

- Sailing Stories

- Sailing Tips

- Boat Reviews

- Book Reviews

- Boats for Sale

- Post a Boat for Sale

- The Dogwatch

- Subscriptions

- Back Issues

- Article Collections

- Free for Sailors

Select Page

Timeline for Sailboats Built In Japan

Posted by Michael Robertson | Boat Reviews

This article is relating to an article in the January 2014 issue.

- International Marine building wooden boats based on Herreshoff 28-foot design.

- Okamoto Shipyard building 35- and 40-foot wooden ketches designed by Garden and commissioned by Hardin.

- Clair Oberly founds Far East Yachts, builds wooden versions of the Alden/Oberly-designed Mariner 31 and Garden-designed Mariner 40.

- Bill Hardin shuts down Okamoto Shipyard, moves operations to Taiwan.

- Kawasaki Dockyard Company, Ltd. (later to become Kawasaki Heavy Industries) purchases both International Marine (which became TOA Yachts) and Far East Yachts (which became Far East Boats).

- Yamaha parlays its FRP expertise to begin building a few small (<15 feet) open boats.

- Far East Boats adds two boats to lineup: Garden-designed Mariner 35 and S&S design #1738, a 40-foot full-keel sloop.

- Far East Yachts builds first hull molds to begin fiberglass construction.

- Far East Yachts ceases construction of wooden boats.

- Far East Yachts introduces Mariner 31.

- Far East Yachts introduces Mariner 32.

- Far East Yachts introduces Mariner 40.

- Far East Yachts introduces Mariner 36.

- Kawasaki Heavy Industries shuts down Far East Boats and TOA Yachts.

- Fuji Yacht Builders builds a couple of one-off boats using Mariner 36 hull mold.

- Fuji Yacht Builders introduces Fuji 35.

- Fuji Yacht Builders introduces Fuji 45.

- Fuji Yacht Builders introduces Fuji 32.

- Yamaha introduces Finot-designed Y29 for sale in Europe.

- Yamaha introduces Y33, Y24, Y25 for sale in North America.

- Fuji Yacht Builders introduces Fuji 40.

- Yamaha introduces Y36.

- Fuji Yacht Builders ceases operations.

- Yamaha introduces Y35.

- Yamaha introduces Y30.

- Yamaha introduces Y37.

- Yamaha ceases exports of recreational sailboats.

Mariner, Fuji, and Yamaha sailboats built for export

About the author.

Michael Robertson

Before he was editor of Good Old Boat magazine, Michael Robertson and his family lived aboard and sailed around on their 1978 Fuji 40. For seven years they explored from Mexico's Gold Coast to Alaska's Glacier Bay to Australia's west coast.

Related Posts

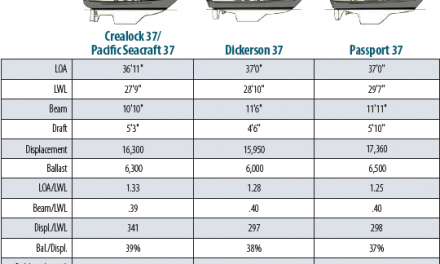

Crealock 37/Pacific Seacraft 37 Boat Comparison

June 10, 2020

Southerly 115

March 1, 2019

August 4, 2020

Oh, How She Scoons!

July 24, 2019

Now on Newsstands

Join Our Mailing List

Get the best sailing news, boat project how-tos and more delivered to your inbox.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

Japanese wooden boatbuilding: history and traditions.

In Western maritime histories, Japan is not generally viewed as a major maritime power. The usual standards for preeminence in this regard have been measured by the reach of a country’s exploration and trade or naval might. Japan’s problem is largely one of timing. It did not become a naval power until the twentieth century, and most Western scholars have interpreted Japan’s maritime importance in light of its reclusiveness—a perception magnified by the timing of European contact. The West’s great era of exploration encircled the globe just as Japan entered its famous 250-year period of exclusion—known as the Edo era—in which foreign travel by Japanese was banned, and contact with most foreigners, especially Europeans (except for the Dutch), was strictly controlled. It has often been written that to enforce these restrictions, Japanese shipwrights were required to build vessels that were inherently unseaworthy, yet another blow to Japan’s maritime reputation. They were never intended to sail out of sight of Japan’s shores. Instead, they sailed through a political and martime era that looked primarily inward, ignoring the horizon. (1)

Japan was an important maritime power in Asia before the Edo era, and even after the era began, for the first few decades of the seventeenth century as a major exporter of silver and copper. Although the Tokugawa shogunate did begin to adopt laws restricting sailing vessels from foreign voyages, there were no actual shipbuilding restrictions. Japanese vessels had, before that time, carried on extensive trade with the Ryūkyū Kingdom (modern- day Okinawa and other islands in the chain) and kingdoms in present-day Korea, China, Thailand, and Việt Nam. The ships that carried out this trade reflected technological influences from Japan’s Asian neighbors, as well as the influence of the Portuguese and Dutch, who had been sailing to Japan since 1543.

A series of edicts restricting trade, Catholic missionaries, and merchants known collectively as Sakoku between 1635 and 1639 eventually resulted in an official ban on all foreign travel by Japanese. Strictly controlled trade contacts with the Dutch, Koreans, Chinese, and Ainu (Japan’s aboriginal population, living mainly in Hokkaidō) were established, but Japan’s own European maritime trade with powers other than the Dutch was banned, and its Southeast Asian trade was only rarely allowed.

Japan’s geography, however, would ensure that the country would necessarily maintain and develop its ship and boatbuilding traditions. The Japanese archipelago is essentially a line of mountains with a relatively limited amount of arable land around the margins. Traveling through the country was difficult, but a few major rivers and Japan’s inland waters offered alternative trade routes to the steep slopes and thick forests of the interior. Furthermore, in seeking to limit the military power of its vassals, the shogunate placed restrictions on the use of carriages and the construction of large bridges. The seas surrounding Japan were the most viable highway for goods, and therefore, the maritime history of the Edo era is largely represented by the thousands of coastal traders that moved goods around the country and the tens of thousands of small boats involved in coastal fisheries.

The larger coastal sailing vessels were called bezaisen , the term seamen and shipowners tended to use. The literal origins of the name are vague but probably refer to vessel type— sen as a word ending means “ship”—and sometimes, the word is romanized as benzaisen . More specific terms for the coastal traders include kitamaesen , best translated as “northern coastal trader,” the type that sailed along the Sea of Japan coast to Hokkaidō. From the north, the most common cargo was herring, salmon, and kelp in trade for rice, salt, cotton, cloth, and sake from the mainland. The general public tended to refer to these vessels as sengokubune , literally “one thousand koku ship.” A koku, or about 330 US pounds, is a traditional Japanese unit of measure; one koku was considered to be the amount of rice it took to feed one person for one year.

While the design and construction of traditional Japanese boats and ships, collectively known as wasen (Japanese-style boats), reflect influences from mainland Asia, the Edo period’s isolation did allow boatbuilders and shipwrights to refine tools, designs, and techniques, creating some unique qualities found in Japanese boats.

Throughout the world, one can find a clear progression of boat development, from the dugout canoe of prehistory to semidugout construction (a dugout lower hull with planks added to the sides) to full plank construction. The same can be found in Japan’s interesting variants of small boats. Semidugout fishing boats can still be found today in the Tōhoku region of northern Japan, and in the 1990s, I interviewed perhaps Japan’s last professional builder of dugouts, a boatbuilder in Akita who last built three for fishermen in the 1960s. The Okinawan archipelago features an iconic boat called the sabani, a type of semidugout, and during my first apprenticeship in Japan in 1996, I studied with the last builder of the distinct taraibune, or tub boat, literally a large barrel used for inshore fishing on Sado Island.

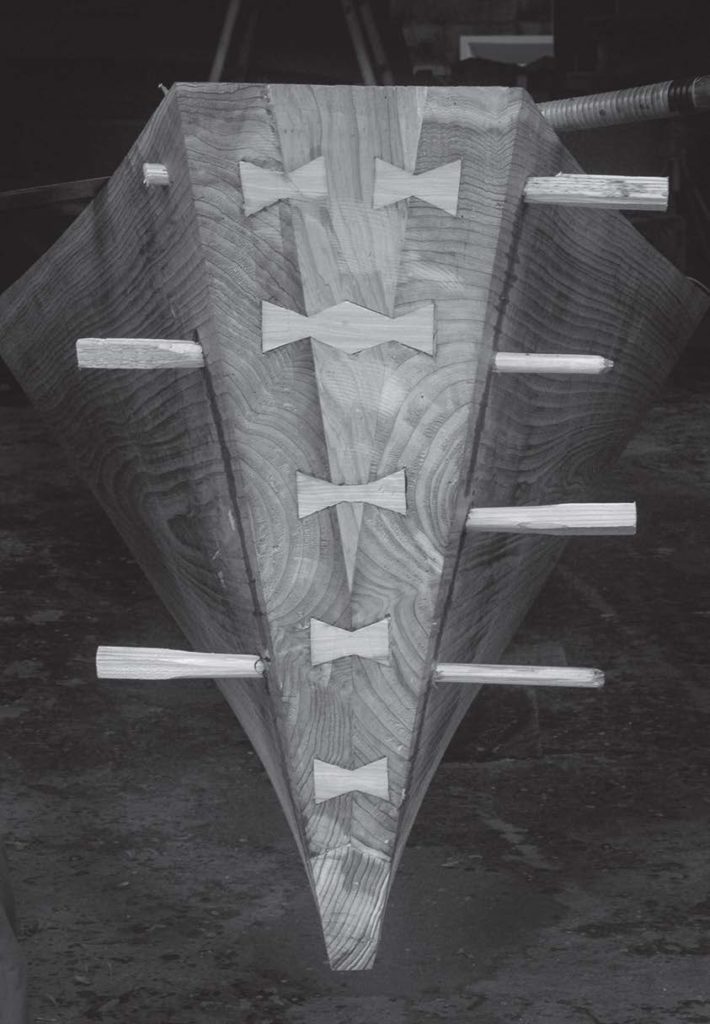

The majority of wasen feature a horizontal plank keel generally twice as thick as the planking with a pair of wide bottom planks rising from the keel at a shallow angle. A pair of top planks run nearly vertical their entire length, meeting the bottom planking at a chine, or hard corner. Where wide planking is built up of several planks, the pieces are edge fastened to each other. In some parts of Japan, sawn frames are installed, but largely the strength of this type of construction rests in the hull itself. In lieu of frames, horizontal beams cross the hull at the chine and the sheer. The beam ends are either tenoned through the hull and wedged from the outside or locked in place with shouldered keys.2 Another feature of Japanese boats is the side planking aft, which often runs past the transom to form a chamber protecting the rudder.

Boatbuilders’ use of edge nails is not unique to Japan, but the technique is definitely highly refined there. Boat nails are made of flat steel, and the holes are cut with a special set of chisels. Today, there is only a single supplier of boat nails in business. This has put a strain on some craftsmen and shows how an important symbiosis exists between craftsmen and attendant crafts that supply their materials.

Another interesting feature of boatbuilding is the process of creating planking with a watertight fit. Using a series of saws, boatbuilders make multiple passes through the seams, a process called suriawase (the term combines the verbs “to rub” and “to assemble”). With each pass, the fit between planks become progressively tighter. Boatbuilders pride themselves on their ability to produce watertight boats without any use of caulking. Only older boats are caulked when they begin to leak.

In my apprenticeships, my teachers stressed the absolute need for me to master the techniques of edge nailing and suriawase. I spent long hours practicing both of these techniques, adhering slavishly to my masters’ instruction. For all five of my teachers, I was their sole apprentice, and each man in his own way communicated his desire to have me carry on his techniques and traditions. One of my teachers was a fourth-generation boatbuilder.

The apprentice system itself represents a major holdover of tradition within the craft of boatbuilding. Learning a craft via apprenticeship with a master is largely forgotten in the West, but in Japan, the notion is well understood and accepted. Unfortunately, Japan’s last generation of boatbuilders today is extremely old. A 2001 survey by the Nippon Foundation in Tokyo found that the average age of Japan’s wooden boatbuilders was sixty-nine. Most never taught apprentices since their careers took place against the backdrop of Japan’s meteoric emergence as one of the world’s largest economies. Furthermore, like practitioners of many crafts, boatbuilders protected their knowledge with an intense secrecy. Many boatbuilders worked entirely from memory, while those that made drawings of their boats left them intentionally incomplete. Even apprentices, unless they were their master’s sons, were kept in the dark, and the phrase nusumi geiko (stolen lessons) is well-known among craftspersons. Apprentices were forced to connive ways to learn crucial dimensions and ratios. One of my teachers told me he slipped back into the workshop at night with a candle and studied his master’s layout of lines.

The traditional apprenticeship was six years with little or no pay. There was no talking in the boat shop and almost no direct instruction. The apprentice was expected to observe the master and learn entirely through observation. A student might spend years just sweeping the shop and caring for the tools, but at the same time, he was expected to watch his master because when the day came for him to actually work on the boat, he was expected to know how to do it. I experienced this pressure with my teachers, and I can say that it certainly focused my attention!

While this type of instruction can seem bizarre or inefficient to the reader, the apprentice’s early months and years in the workshop are hardly wasted in the Japanese context. In order to succeed, the apprentice must learn patience and perseverance and hone his powers of observation. It is a values-based education, something understood to be absolutely necessary before the apprentice can begin to learn the craft. As arduous and inefficient as it may seem, this system produced craftsmen of remarkable skill.

With almost no written record, the craft of boatbuilding today is in real danger of being lost, along with many other traditional skills that have depended on the master-apprentice relationship for sustenance. My research has involved working alongside boatbuilders and recording their designs and techniques. I produce measured drawings of the boats I have built, and I hope to find venues in the future to teach these skills. I have also published the results of my research in magazines and two books. While my efforts to disseminate this information are an obvious break with tradition, the potential loss of a such a unique and refined craft culture strikes me as tragic.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- See Dr. Hiroyuki Adachi’s book Nihon no Fune—Wasen Hen ( Ships of Japan—Indigenous Designs) (Tokyo: Museum of Maritime Science, 1998).

- A tenon is a square or rectangular pin cut into the ends of a beam, which fit into a corresponding mortise, or hole, cut into the face of the planking.

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

- MarketPlace

- Digital Archives

- Order A Copy

A definitive look at Japanese boatbuilding

It was about seven years ago that Ocean Navigator publisher Alex Agnew and I drove up one night from Portland up to Brunswick, to Bowdoin College, to hear wooden boatbuilder Douglas Brooks speak. Alex and I share a fascination for boats of all kinds, wooden in particular, but I was doubly drawn by a distinct linguistic allure. I had been studying Japanese language for several years and Douglas Brooks was and is the leading sensei of Japanese wooden boatbuilding.

Mr. Brook’s talk not only opened its audience’s eyes to a boatbuilding art developed with hardly a whiff of influence from the world of Western craftsmanship and technique, but it also unveiled again that clichéd inscrutability that has long described Japanese ways.

For starters, the Japanese are dumbfounded that American and European boatbuilders caulk their boats from the outside. After all, they say, that’s the side the water is on. The Japanese caulk from the inside and then only after their boats become very old. In fact, they don’t need to caulk new wooden boats at all due to a technique Brooks explains in detail in his new book, straightforwardly entitled “Japanese Wooden Boatbuilding.”

This is the story of the author’s apprenticeships with Japanese masters, the last of their kind building unique traditional boats of endangered styles. It is part ethnography, part instruction, and part the personal story of a wooden boatbuilder fueled by a passion to preserve a centuries-old craft on the brink of extinction. Over the course of 17 trips to seek out these elderly masters, Mr. Brooks built boats with five of them, and for most he was their sole and last apprentice.

At 320 pages with 378 color photographs and 36 drawing, a launch into Japanese Wooden Boatbuidling is a leap into an exotic new world. Design, workshop and tools, wood and materials, joinery, fastenings, propulsion, ceremonies—this comprehensive volume will be of interest to boatbuilders, woodworkers, and anyone who has ever been impressed with the marvels of Japanese design and workmanship.

Hijouni ni omoshiroi. Extremely interesting.

Signed and inscribed copies are available directly from the author at www.douglasbrooksboatbuilding.com . Buying from this site directly supports Mr. Brook’s ongoing research.

By Ocean Navigator

Wasen Mokei 和船模型

Modeling traditional japanese water craft.

Glossary of Japanese Boats and Terms

[Updated 4/15/23]

This is a list of terms relating to traditional Japanese boats, or wasen, that I’ve collected in my notes. This is not even close to being a comprehensive list, and the descriptions given are really quite basic. I’ve compiled this list from my own studies, and with the help of many others who are more knowledgeable than myself.

Yubune 湯船 – a bath boat from the Edo period.

Sources of information include the book Funakagami, books I’ve collected by Professor Kenji Ishii, the works of Douglas Brooks, information parsed from the Internet, and information I’ve gathered personally through visits to the Toba Seafolk Museum, the Urayasu Museum, the Edo Tokyo Museum, and the Ogi Folk Museum.

At some point, I hope to write more complete and detailed descriptions for each of the terms. Probably, this will happen one term at a time, as I learn about each one and study them in more depth. However, the list of boat types seems endless, and I have only a small number listed here. I have many more that are not in this list, so I will expand it over time.

I’ve grouped these terms in a way that seems most meaningful to me. I’ve sorted alphabetically where possible, but, more importantly, in order or relevance. Note that this page is under construction and will be revised as time permits.

For the boat types and general terms, I’ve tried to include the terms written in kanji (chinese characters adopted for the Japanese language). However, in many cases, I’ve only found the names written in katakana (one of two phonetic alphabets used in Japanese). Boatbuilding terms, in particular, seem most commonly written using katakana.

I include the Japanese text in order to make it easier to search the web for images and information. Simply copy the characters and past them into your web searches and you’ll find a lot more than simply using the romanized words.

General Terms

Wasen 和船- meaning “traditional Japanese boat”. A general term for any wooden boat of Japanese style.

Amibune 網船 – a general term for a net fishing boat.

Bezaisen 弁才船- a class of large coastal transport, of which there are several types.

Gyosen 漁船 also Tsuribune 釣船 – fishing boat.

Junkōzōsen 準構造線 – term for a boat with a semi-structured hull. This basically a mixed construction with a dugout hull forming the basis of the boat. Planking and beams are added to increase the capacity and sturdiness of the boat.

Kensakibune 剣先舟 – “sword-tipped boat” is a boat built without a stem for the cutwater. Instead the bow planks fasten directly together, creating a sharp-tipped bow. This style of construction appeared in the Yodogawa and Yamatogawa river areas. The type may also be referred to as Nimai Miyoshi, because the cutwater is made up from the two sheets of the hull planking coming together.

Kōzōsen 構造船 – boat with a fully planked hull, an evolutionary extension of the Junkōzōsen, with the dugout portion of the hull being replaced by planked structure.

Kawabune 川船 – general term meaning riverboat.

Kuribune 刳船 – term for a boat with a dugout hull.

Sengokubune 千石船- meaning “1000 koku ship”. A common term for bezaisen.

Tsuribune 釣船 also Gyosen 漁船 – fishing boat.

O-mawashi a general classification of boats designed long distance, sea voyages, such as bezaisen or sengokubune.

Ko-mawashi a general classification of boats designed to operate on both rivers and seas, such as godairikisen.

Uchikawa-mawashi a general classification of river-going boats, such as chabune, chokibune, takasebune, etc.

Aganogawa Kawabune 阿賀野川川船- a long, narrow riverboat of the Agano river used in cast net fishing.

Ayubune アユブネ – A term for a riverboat used in fishing a popular sweet fish called Ayu. The term is used in various regions of Japan and there is no single type of Ayubune.

Bekabune ベカブネ or Beka ベカ- a one or two-person boat used in Tokyo Bay for shell fishing or gathering seaweed. The term might be used in other regions, as are the terms Beka, Kawabeka, and Noribeka. Bekabune are sometimes carried aboard larger boats called Utasebune.

Chabune 茶船 – a general term for a small boat used for transport on rivers during the Edo period; the name refers to a small riverboat used for selling food and drink (Funakagami).

Chokibune 猪牙舟 – a river boat used as a water taxi during the Edo period. Most well know for carrying passengers to the pleasure district of Edo. Also known as a Sanyabune .

Choro 丁櫓 – This is a term used for a small, sculled boat. The usage of the term varies depending on region. In Mie prefecture, this type of boat was used close to shore for pole and line fishing and for catching sea cucumber.

Godairikisen 五大力船 – a large, local transport capable of operating on rivers or on the ocean.

Gozabune 御座船 – large boats used by aristocrats or high-ranking warriors. Often decorated for fesitvals. Built for use both on rivers and on ocean. Seagoing Gozabune were essentially warships used to demonstrate a warriors prowess during peaceful times. River boats used for the purpose were called Kawagozabune .

Hacchoro 八丁櫓 – an 8-oar boat used for pole-and-line fishing of bonito. At one time, boats of this type from Yaizu were commissioned as escort boats for the Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Higaki Kaisen 菱垣回船 – A bezaisen of the Higaki trade guild, operated between Osaka and Edo (e.g. Naniwamaru).

Hiratabune 艜船 – Hiratabune is a general term for various cargo riverboats. On the Tonegawa, the name refers to a large riverboat from 50 to 80 feet long, similar to the Tonegawa takasebune . Long and narrow, flat bottom boat, used to transport freight. The largest had a capacity of 300 koku (Deal). Large hiratabune and takasebune can be easily confused due to their similar appearances, but hiratabune generally have a cutwater or stem.

Hobikisen 圃引き船 – a side-trawling fishing boat used on Lake Kasumigaura.

Honryou ホンリョウ or Honryousen – a small riverboat from Niigata prefecuture used for fishing and sometimes for carrying gravel.

Isanabune 鯨船 – An old term for a fast, multi-oared boat used for whaling. A more common term today is kujirabune.

Jarisen 砂利船 – Gravel hauling boat.

Kaidenma or Kaitenma 櫂伝馬 – an oar-driven cargo boat that is used in Shinto festival boat races, one of the events in the Sumiyoshi Matsuri , the Shinto festival of the sea in Hiroshima prefecture, or the Oshima Minato Matsuri in southern Wakayama prefecture.

Kasaibune 葛西舟 – Fertilizer, or Night Soil, carrying boat.

Katsuobune カツオ船 – a boat used for bonito fishing. 8-oared variant is sometimes also referred to as a Hacchoro 八丁櫓.

Kitamaebune 北前船- a northern port bezaisen (e.g. Michinokumaru, Hakusanmaru).

Kōjisen 工事船 – Construction boat.

Kurawankabune or kurawanka くらわんか船 – a local, informal name (and not a very nice one) for a chabune used on the Yodo river to sell food and drink to passenger boats.

Kujirabune 鯨舟 – a colorfully painted whale boat used in whale spear fishing from Shiroura, Mie prefecture. Same type of boat was used for pole-and-line fishing of bonito, and was called a Hacchoro 八丁櫓. (13.7m, 2.3m)

Marukibune 丸木舟 – a type of boat with a dugout hull. See the general type, Kuribune .

Marukobune 丸子船 – a traditional design unique to Lake Biwa. The name is apparently a reference to the round shape of the hull’s cross-section. The type was used extensively during the Edo period to carry cargo across the lake and features a heita-style bow with vertical stave planking, unique to Lake Biwa boats.

Mizubune 水船 – a water carrying boat (from Funakagami)

Mokaribune (see Zaimokubune )

Mossoubune 持左右舟- a tow boat used in whaling.

Nitaribune 荷足船 – a cargo boat used on the canals of Edo.

Nouninawase ノウニンアワセ – a Niigata rice field boat (tabune), sometimes used for hauling gravel.

Sandanbo 三反帆 – a small 3-sail (hence the name) riverboat used to ferry passengers on the Kumano river in Wakayama prefecture.

Sanjukokubune or Sanjikkokubune 三十石船 – a 30-koku transport that was used on the Yodo river system for transporting passengers and goods. These boats provided regular, scheduled service between Ōsaka and Kyōto, with over 300 trips a day at its peak. Boats would leave Ōsaka in the morning and arrive in Kyōto in the evening, and would leave Kyōto in the evening, and passengers would sleep over night, arriving in Ōsaka in the morning.

Satsumagata サツマガタ – Literally, a Satsuma-style boat used for mackerel and marlin fishing on the west coast of Satsuma.

Sedoribune 瀨取り船 – a small boat for loading and unloading cargo from larger ships.

Sekobune 勢子舟 – a chaser-type boat used in whaling. See kujirabune.

Sobakiri-uri no fune そば切り売りの舟 – buckwheat noodle selling boat.

Sosuibune 疏水船 – Literally, a canal boat. The term refers to a boat type developed in the late 1800s in the Lake Biwa region when canals were cut connecting Kyōto to Lake Biwa for transportation and drinking water. Sosuibune were used for carrying rice and firewood to Kyōto. The boats had a capacity of 30 koku and measured around 35 shaku in length and 6 shaku in width. These boats were built with the heita-style bow, common to boats on Lake Biwa.

Suzumibune 納涼舟 – a boat for enjoyin a cool evening breeze

Tabune タブネ – a ricefield boat. Usually these were no more than large tubs pushed or pulled along flooded rice fields.

Takasebune 高瀬船 – long and narrow riverboat with a flat bottom, used to transport freight, typically. Large takasebune and hiratabune can be very similar in appearance, but takasebune generally have a flat bow with no cutwater.

Taraibune たらい舟 – a one-person tub boat from the Niigata coast, most commonly from Sado island, used for inshore and shell fishing.

Tarubune 樽舟- a barrel retrieval boat used in whaling

Taru Kaisen 樽廻船 – a barrel carrying bezaisen, usually carrying sake or miso, but often carried other cargos.

Tenma テンマ or Tenmasen 伝馬船- common term for a workboat or lighter.

Toamibune 投網舟 – a cast-net fishing boat.

Tosen 渡船 – a river ferry (from Funakagami).

Tsukimibune 月見船 – boat for moon viewing in Autumn.

Ukaibune 鵜飼船 or Ubune 鵜船- a cormorant fishing boat.

Uma-sen 馬船 – a ferry used for carrying horses, cattle, and carts.

Uma Tosen 馬渡船 or Saku Tosen 昨渡船 – double-ended ferry for carrying horses and cattle.

Urobune 売ろ舟 – a boat that sells something.

Urourobune うろうろ舟 – casual wandering boat. Selling light refreshment (drinks, watermelon) among pleasure boats.

Utasebune 打瀬舟 – Term for a side-trawling fishing boat. In Hokkaido, utasebune are small fishing boats with two masts, rigged with triangular sails. The ones used on Tokyo Bay are large boats with two masts, carrying square sails.

Uwanibune 上に船 – small boat for unloading cargo from a large anchored boat; lighter.

Watashibune 渡し船 – General term for a ferry boat.

Yakatabune 屋形船 – a large river-going pleasure boat with a deck house that could accommodate a large number of people for an afternoon or evening of entertainment.

Yanebune 屋根船 – a roof boat, like yakatabune, but smaller.

Yubune 湯船 – a bath boat (from Funakagami). A floating public bath typically used by cargo ship crews and dock workers (Deal).

Yuusen 遊船 – excursion boat, pleasure boat.

Yuusan bune 遊山船 – cruising boat, enjoying-life boat.

Zaimokubune 材木船 or Mokaribune – Lumber Boat. A raft-like boat used on Tsushima Island for harvesting seaweed.

Zutta Tenma – “crawling” workboat, Himi name for a tabune.

Atakebune 安宅船 – A large, lumbering, castle-like war vessel used during the Warring States period. Mounted with a large protected structure housing two or more decks, this was the largest type of Japanese warship. During the Tokugawa era, these ships were banned.

Sekibune 関船 – Used in the Warring States period, smaller and faster war vessel than the Atakebune. For this reason, they are sometimes referred to as Hayabune, or fast boat. It has a protected structure on the main deck, usually with some protection for those on the open top deck. During the Tokugawa era, the use of these ships was severely curtailed, though many daimyo used them as Gozabune – highly decorative personal yachts.

Hayabune 早船 – Fast boat. Because Sekibune are much faster than Atakebune, they are sometimes referred to as Hayabune. The term may also used for a boat used designed to race, such as the boats used in a ceremonial race on the Kumano river.

Kobayabune 小早船 or simply Kobaya 小早 - Small, fast boat. Small, is relative, and a 55-foot row galley is smaller than most Sekibune, so it is referred to as a Kobaya.

Parts of the Boat

These terms are very regional, so they may differ depending on the boatbuilder and the locale. In some cases, I’ve listed more than one term together, but there may be others as well.

Akaita – soft sheet copper

Ban バン – Himi term for a small deck at the bow. See Kappa.

Chigiri チギリ or Chikiri チキリ- a wooden dovetail key used in various parts of Japan to fasten together adjoining planks or logs.

Chiri チリ – This is a term for a decorative board that covers the end grain of the hull planks at the stern on many boats.

Chyou チョウ – Toyama term for a central bottom board. See Shiki.

Donoma -The open deck space in the middle of the bezaisen.

Funabari フナバリ – beam.

Funakugi 舟釪 or フナクギ – boat nails.

Furikake – lower side planks of a marukobune

Hako ハコ or Tomobako トモバコ – Toyama term for wedge-shaped box structures sometimes present behind the transom, connecting the garboard planks hull planks.

Haritsujiki – The haritsujiki was a book containing location specific directions for reaching specific destinations.

Hayao ハヤオ – rope attached to the ro, or sculling oar, to help control its motion.

Hayaoneko ハヤオネコ – wooden piece on the inside of the hull, to which the rope for the sculling oar is attached.

Heita – a style of bow construction found among many types of boats on Lake Biwa including the marukobune. A heita bow is constructed of sharply angled vertical staves, creating a rounded shape.

Ho 帆 – sail.

Hobashira 帆柱 – mast.

Hogeta 帆桁 – yardarm.

Hojirushi 帆印 – The black markings on the sail of the bezaisen that identify the ship’s owner.

Hozo ほぞ – tenon.

Hozoana ほぞ穴 – mortise.

Hozurikuda – The cable that runs from the top of the mast to the bow touches the sail when it is unfurled, so it is wrapped in a wooden sheath to avoid damaging the sail.

Ippon Miyoshi 本水押 – A type of bow where the hull planks fasten to a single stem to for the cutwater or miyoshi.

Jyabara 蛇腹 or Jyabara-gaki 蛇腹垣 – A fence made of woven bamboo that was temporarily attached to the hull of benzaisen to protect and hold cargo in place on deck. In the Meiji period, these became permanent fixtures.

Jyou-toma 常苫 – A temporary house structure erected on the deck of a benzaisen to shelter cargo.

Kai カイ – paddle.

Kaji 舵 – rudder.

Kajiki カジキ or Kanjiki カンジキ – garboard planks. Sometimes called Nedana.

Kanzashi – mooring bits usually found near the ends of a beam – short post for tying of lines, often square tapered, with a faceted nob at the end.

Kappa カッパ – raised fore deck to protect from spray. See Ban.

Kasagi カサギ – mast gallows

Kawara カワラ – bottom (also shiki)

Koberi コベリ- rubrail

Konagashi コナガシ or Konaoshi コナオシ – triangular piece located behind the Miyoshi that effectively extends it underneath the bow of the boat, allowing the garboard planks to rise up at the bow.

Kotsunagi コツナギ – mooring beam

Magari マガリ – half frames supporting the hull planks. See Matsura.

Makinawa or Makihada – caulking bark of the maki tree

Marikuchi or Maruguchi マリグチ – round hole in the stern beam for fitting a rudder.

Matsura マツラ – frame. See Magari.

Miyoshi 水押し or ミヨシ – stem, cutwater. This may further be identified by type. Ippon Miyoshi, 一本水押し, is a bow type in which the hull planks are attached to a stem. This is a very common type among wasen. Nimai Miyoshi, 二枚水押し, is a bow type in which there is no stem. Instead, the hull planks are fastened to each other creating a sharp bow. See the general term Kensakibune.

Muchugokaku – A type of foghorn powered by an attached bellows. Sounded when entering or exiting a harbor to alert nearby ships.

Nedana ネダナ – Lower, or garboard plank. Sometimes called Kajiki.

Nimai Miyoshi 二枚水押 – Type of bow where the side planks of the hull come directly together to for the cutwater or Miyoshi without the supporting stem that appears in the Ippon Miyoshi type bow. This type of bow appears in a boat type called a Kensakibune.

Nobori – a pole-mounted banner or flag, usually tall and rectangular

Omoki or Omogi オモキ – a log carved out in an “L” shape forming the chine for a boat. The log planks of a marukobune.

Ro 櫓 or 艪 – a sculling oar

Rogui ログイ- the pivot pin for a sculling oar

Sagari 下がり- a tassle decoration found on the bow of some larger boats

Sao 竿 or サオ – a pole, in this case used for propelling a boat.

Sekidai セキダイ or Namigaeshi (波返し) ナミガエシ – boards fixed at the rubrail which extend out from the hull and run the length of the boat, used to improve stability in rough seas.

Shiki シキ – bottom (also kawara)

Shikiriita シキリイタ – floor timber

Tana タナ – planking strake.

Tatara タタラ – wooden nail fastener.

Tateita 竪板 – an end plank at either bow or stern.

Tatematsu タテマツ – a vertical support connecting upper and lower funabari.

Te-kaki テカキ – hand paddle (Tosa)..

Todate トダテ – transom.

Toko トコ or Ootoko オオトコ – stern beam (a heavy beam).

Tomo 艫 – the stern of a boat.

Tomobako トモバコ – see Hako.

Tomo no ban トモのバン – Himi term for a small raised deck at the stern of a boat.

Tsunatsuke ツナツケ – a small beam located near the bow or stern for tying ropes to.

Uchimawashi – Whenever the yardarm is raised and lowered, this component fulfills the role of connecting it to the mast so that the yardarm can slide smoothly up and down the mast.

Urushi 漆 – a lacquer that is sometimes used for caulking or gluing wooden pieces together. The liquid comes from the sap of a tree that is related to poison sumac. Until it is cured, it is poisonous, an extreme irritant, and has to be handled very carefully.

Uwadana ウワダナ- shear plank.

Uwakoberi ウワコベル – caprail.

Wajishaku – A magnetic compass used by sailors to navigate the ship.

Yaho や帆 – fore sail.

Yahobashira や帆柱 – fore mast.

Yakata 屋形 – deck house or cabin

Boating and Fishing Terms

Gyomō 漁網 – Fishing net

Isomegane イソメガネ – a wooden box with a glass bottom, used to see into the water for spearing octopus, sea cucumber, abalone, etc. In Fukui prefecture, this type of fishing is called Isomi.

Sendō 船頭 – Boatman.

Tsurizao 釣り竿 – a fishing pole.

Construction Techniques

Omoki-zukuri 面木造り – carved log construction style (see Kuribune), with planks or log-planks fasened together with wooden fasteners called Chikiri.

Ita-awase – fitted plank construction.

Suri-awase – sawn plank fitting.

Kanna – plane

Kasugai – iron staples

Nokogiri – a common name for small handsaw

Nomi – chisel

Sumitsubo – ink line tool

Sashigane – flexible square made of thin steel

Sumisashi – bamboo pen with split, beveled tip

Surinoko – a type of handsaw

Toishi – waterstone

Tsubanomi – a sword-hilt chisel

Wakitori – a type of plane

Share this:

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- When and How We Started

- Clubs in Japan

- 48th Exhibition 2023

- 47th Exhibition 2022

- 46th Exhibition 2021

- 44th Exhibition 2019

- 43rd Exhibition 2018

- 42nd Exhibition 2017

- 41st Exhibiton 2016

- 40th Exhibiton 2015

- 39th Exhibiton 2014

- 38th Exhibiton 2013-1

- 38th Exhibiton 2013-2

- 37th Exhibiton 2012

- 36th Exhibiton 2011

- 35th Exhibiton 2010

- 27th Exhibition 2002

- 26th Exhibition 2001-1

- 26th Exhibition 2001-2

- Japanese Ships in chronological order

- A. Large Vessel

- B. Seaweed Boats

- C. Fishing Boats

- D. Miscellaneous purpose vessel

- Articles on Japanese ships and boats from The Rope News

- TAJIMA Isao Work Collection

- World Modelers

- Japanese Ships

Japanese Sailing Ships and Boats

In chronological order, 8th century.

15th~16th Century

17th Century

18th Century

19th Century

20th Century

- Scroll to top

SAILBOATS - YACHTS - DINGHYS FROM JAPAN

- ABOUT THIS SITE

Search Boats

Boats for Sale!

Good-conditioned used boats are ready for export from Japan.

Price: ASK JPY

Hyogo, Japan

Price: 12,800,000 JPY

Price: 1,780,000 JPY

Price: 6,980,000 JPY

Price: 33,800,000 JPY

Price: 11,800,000 JPY

CR-28EX TWIN

Price: 8,800,000 JPY

Price: 6,780,000 JPY

Price: 9,780,000 JPY

Price: 3,880,000 JPY

SEARCH BY MAKE

SEARCH BY LENGTH

- 20ft - 25ft

- 25ft - 30ft

- 30ft - 35ft

- 35ft - 40ft

SEARCH BY PRICE

- 0 JPY - 500,000 JPY

- 500,000 JPY - 1,000,000 JPY

- 1,000,000 JPY - 2,000,000 JPY

- 2,000,000 JPY - 2,500,000 JPY

- 2,500,000 JPY - 3,000,000 JPY

- 3,500,000 JPY - 4,000,000 JPY

CALL +81 (0)4 7135-2760

- Competitions

- British Yachting Awards

- Print Subscription

- Digital Subscription

- Single Issues

- Advertise with us

Your special offer

Subscribe to Sailing Today with Yachts & Yachting today!

Save 32% on the shop price when to subscribe for a year at just £39.95

Subscribe to Sailing Today with Yachts & Yachting!

Save 32% on the shop price when you subscribe for a year at just £39.95

Sailing in Japan

Japan remains an obscure sailing ground, despite being a highly developed country. nick and jenny coghlan enjoyed a surreal cruise.

Preparing for Sailing in Japan

E verybody had warned us that the Japanese love paperwork. So as Bosun Bird, our Vancouver 27, worked her way northwards through the islands of the western Pacific, every so often we’d crank up the Iridium satphone to find out what we needed to do before entering the country. By the time we reached Guam, the American territory and military base that was to be our jumping-off point for the 1,400-mile crossing to Kyushu, we were getting desperate. We finally got hold of a seemingly helpful young lady:

“You are very welcome. Please send now fax with exact arrival time and place. Thank you.”

“OK. Can we send an email instead?”

(Repeat this exchange several times, until the lady quietly hangs up.)

Finding a fax these days is challenging; the Guam Mission to Seamen finally located a dust-covered machine in their junk cupboard. It was with nostalgia and amazement that we plugged it in, and there was that long-forgotten whirring and beeping. With a mental shrug – who can estimate an arrival time after a crossing of 1,400 miles? – we sent a message and put to sea.

Next day, on the horizon to starboard we had the low flat outline of Tinian: from here the Enola Gay, an American B-29, took off before dawn on August 6 1945, to drop the first atomic bomb. Idly, I wondered if it was going to be possible to talk to Japanese about the war.

It soon turned into a rough passage. But most worrying was the shipping. We’d installed an AIS receiver in New Zealand, anticipating heavy traffic in these waters. It was difficult as we closed on Kyushu not to feel panic as the tiny screen of our chart-plotter showed up to 40 targets at a time. But at last, after a nervous night dodging small fishing boats with unfamiliar light arrays (and none of them with VHF) we motored into the calm waters of the great bay of Kagoshima-wan.

Sailing in Japan: Unknown territory

An unfamiliar scent of spruce wafted towards us. A high-speed hydrofoil buzzed past at 35 knots; a propeller plane with that famous red-sun symbol flew low to take a look at us. And at the head of the bay, Sakajima volcano was having one of its frequent bouts of activity.

We zigzagged in to the port through a maze of concrete breakwaters. Out of the corner of my eye I saw fifteen or so men, mostly in uniform, standing sharply to attention on one pier. One of them saluted. We paid no further attention, occupying ourselves instead with a newly learned tie-up routine (nose-in, at right angles to the wall, secured on each quarter to buoys). Old friends Mel and Phil, on Mira, had beaten us by two or three days and welcomed us, babbling with their news; Mel had an ugly waffle-shaped scar on her thigh, from when they’d taken a knockdown and she’d fallen on the stove.

By sheer chance, and for perhaps the first and last time ever, Bosun Bird had arrived exactly when we said we would. Yes, we now realised, those men in the Toyota blazers, peaked caps and white gloves were our reception committee. Two-by-two they clambered down, each pair presenting us with the same long and baffling ‘General Declaration.’ The final couple politely gestured that we should land, and ushered us into their car. We had no idea what was going on. More arcane paperwork at their office, smiles, then they drove us back. In the cockpit we found a case of Kirin beer, a large watermelon and two packages of sushi. Phil shrugged with a smile:

“That’s Japan for you. Just strangers making you welcome.”

Sailing in Japan has its challenges. For one, the bureaucracy never gives up. For every single destination other than four or five designated Open ports, you must have specific entry permission. Early on, we learned that it is wise to request permits for every conceivable stop. But the officials are charming.

As we waited patiently in Hiroshima one morning for our next list of authorised ports to be typed up, the woman in charge of the office pulled some coloured squares of paper from under the counter. She patiently instructed us on how to fold them so as to make origami cranes.

Sailing inshore waters in summer is generally tranquil, the winds light and variable: you may need to use your engine a lot. We did need to keep an eye open for warnings of typhoons (the North Pacific equivalent of hurricanes/cyclones), but the two to three days’ notice that we always had, coupled with the large number of typhoon-proof artificial harbours, meant that this was not a major concern.

When sailing in Japan, in many areas there are strong tides and currents to compete with too. Kanmon Kaikyo, the strait between the great islands of Kyushu and Honshu, runs at up to 11 knots: large illuminated boards at either entrance indicate the current speed, direction and tendency (rising/falling) in real time. There are few natural anchorages anywhere: fishing harbours take up every imaginable nook, and tying up to vertical and barnacle-encrusted walls when the tidal range is 15ft is challenging. We learned wherever possible to search out floating pontoons, feigning linguistic ignorance when some official would appear and make the universal hands-crossed ‘not permitted’ gesture.

Gaijin gaffe

Then there are those infamous cultural challenges. Every Gaijin (foreigner) who travels to Japan has his or her gaffe to recount, and we were no exception. Having been shown by a friend all the rituals that must be scrupulously observed in Japanese public baths, we ventured for the first time on our own. The captain was luxuriating, naked and alone in neck-high hot water, with a magnificent view over the South China Sea, when there was a rustle. The paper sliding door to the men’s section slid open. There stood a naked woman, with her hand to her mouth in a silent “Oh!”

I thought, “Silly her, wrong side,” and dozed off again. Ten minutes later in came a most apologetic bath attendant: “So sorry, captain-san, wrong side!” How could this be? Well, in the spirit of gender equality, each day the men’s and women’s sides were reversed, so everyone could have a turn with the view.

But the bucolic islands of the fabled Inland Sea, possibly the only place where old Japan lives on, were unforgettable. Tiny villages are built round harbours, their narrow streets lined with centuries-old wooden houses, many of them closed up as the young people have all gone to the cities. On one such island, a Buddhist monk introduced himself to us on the pontoon, in flawless English. He was the designated yacht-greeter; he’d worked in Silicon Valley. Would we like to come and see his temple?

He took us out to lunch, and then we climbed the hill in sultry summer heat, insects buzzing. After we had had green tea on the floor in his spotless, spartan wooden home, he took us into the woods. A small granite marker had a haiku inscribed on it. It was 1,000 years old, and referred to this very spot, to the heat, the cicadas and the rustling of the stream at our feet.

Travelling by sailing boat gave us a kind of club membership, an entrée to Japanese society that many visitors otherwise find elusive. Michan, who liked to crew for racers at Kagoshima, became a friend and interpreter, puzzling with us over her own culture and checking with her pocket translator as she took us from temple to shrine; at our farewell, she had Jenny try on her grandmother’s kimono. Ishii-san, whom we met over endless toasts of sake and shochu on his boat Skal, at Hirado, phoned the manager of his distant marina at 0100 that night, to arrange winter berthing for us.

Nearly all the Japanese cruisers, sailing in Japan, seemed to be middle-aged men singlehanding, who didn’t know how to cook, so we were invited out constantly.

And the war? I hesitated. But one day a sailing friend we made in Fukuoka, Nori-san, took us to a small museum at an airfield that had been used to launch kamikaze missions in 1945. Eventually he opened up.

“I was four. I can remember the B-29s coming over. My elder brother, he was 16. He ran away to become a pilot. It was the patriotic thing to do.”

He paused for a long time. “Later we found out what had happened. All the records still exist. He was one of a flight of six. Three crashed before they reached Okinawa. He was shot down. I don’t think I can ever forgive our leaders from that time. Only 16.”

Sailing in Japan turned out to be the most foreign, exotic yet hospitable place we have ever visited.

Fifteen months on from Kagoshima, we were waiting at Shimoda, at the entrance to Tokyo Bay, for a gap between typhoons before launching into our 3,500-mile crossing to Kodiak, Alaska. A local schoolteacher had taken us under her wing. One day she took us to meet another friend, the abbess of the local monastery. We knelt uncomfortably as the abbess conducted the arcane tea ceremony and said a few formal words. Then the abbess looked at us, smiling and expectant.

“Nicholas-san, Jenny-san,” said our teacher friend. “I brought you here because it is in this temple that the Shoguns would always come to be blessed before making the final sea crossing to Edo (Tokyo). The abbess has just wished you well, in the same way that her predecessors did, for hundreds of years.”

The abbess bowed towards us and put her hands together. In hesitant, careful English, she said simply:

“Good wind.”

About Nick and Jenny Coghlan

Nick and Jenny Coghlan are dedicated cruising sailors, based in Salt Spring Island, British Columbia, Canada. They have sailed far and wide, from Alaska to Easter Island.

- Boat Test: C-Cat 48

- Sailing French Polynesia: The Dangerous Archipelago of Tuamotus

- Boat Test: Bali Catsmart 38

What’s your bucket list sailing adventure?

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Win Sailing Charter in Greece for Two: GlobeSailor’s Competition

Tom Cunliffe: What to do with no Berths in Town

Dream Guarantee: Dream Yacht’s New 10% Income Offer

Offering a wealth of practical advice and a dynamic mix of in-depth boat, gear and equipment news, Sailing Today is written cover to cover by sailors, for sailors. Since its launch in 1997, the magazine has sealed its reputation for essential sailing information and advice.

- British Yachting Awards 2022

- Telegraph.co.uk

ADVERTISING

© 2024 Chelsea Magazine Company , part of the Telegraph Media Group . | Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

How To Sail From California To Japan

Last Updated by

Daniel Wade

August 30, 2022

Japan and California are an entire ocean apart. But on a sailboat, they're closer than you think. Here's how to sail from California to Japan.

You can sail 5,150 nautical miles from California to Japan directly through the Pacific Ocean in about 30 to 60 days. You can also sail to Hawaii, which is the halfway point, or stop in the Marshall Islands and the Marianas Islands closer to the Japanese mainland.

In this article, we'll cover all the main steps to take your sailboat from the coast of California to Japan. We'll cover the distance, average time, along with several island destinations along the way. We'll also cover how to choose the right sailboat and the possible hazards along the way.

The information used in this article comes from a variety of sources, including the testimony of sailors who have made the journey themselves.

Table of contents

Can A Sailboat Get To Japan?

Sailors often question if a sailing trip to Japan is worth it—or even possible. As it turns out, Japan and California have a coastline along the massive Pacific Ocean, albeit on opposite sides of it. Sailing from California to Japan is an extensive journey, but it's well within the realm of possibility if you have the right boat and the right amount of experience.

Many sailboats have made the trip from California to Japan and even further to other nations such as Australia. There are many places to stop along the way, as the route between the continental US and the Japanese islands is dotted with small atolls and island chains. As a result, you don't have to store supplies for the entire journey if you want to stop along the way.

How Far Is California From Japan?

A single, non-stop sailing trip from California to Japan is about 5,150 miles. This is a considerable distance for a sailboat to travel and will likely take a month or two to achieve. Assuming your sailboat travels at 7 knots, it'll take around 30 days. This doesn't take into account stops and variations in wind speed, so it's best to expect a 45-day trip or longer.

Hull speed is a major factor to consider when choosing a boat for this long journey. A knot or two in average speed variation can add several days to the length of the trip, which can spell trouble if you only planned enough food and water for the shorter journey. Always prepare and provision for 25% to 50% longer than you expect to spend on the water.

Do You Need A Passport To Sail To Japan?

Yes, you'll need a passport to sail to Japan. You'll also need to get in touch with a local marina in your destination area. The marina staff can help you set up a meeting with local customs and immigration services.

Because you are arriving on your own vessel, you'll need to fill out special declaration paperwork and may be subject to an inspection. Additionally, you'll likely be limited in how long you can stay in the country.

The laws in Japan are different from the United States, and while in Japan, you and your vessel are subject to the laws of the land. Some items that are legal in the United States and in California are not in Japan, so be sure to research what you can and can't have aboard before departing. The same is true in all of the island nations and destinations along the way, except Hawaii.

Provisioning For Sailing To Japan

The absolute minimum amount of provisions you need should span a month, though it's always wise to prepare for a much longer journey. Here is a basic list of items to stock in adequate supply, along with some optional items that can make your trip safer and more comfortable.

- Dry non-perishable foods

- Fresh drinking water

- USCG supplies (flares, life jackets, fire extinguisher)

- Flashlights and batteries

- Spare lines

- Fiberglass patch kit

- Sail patch kit

- Fuel, water, and oil filters

- Satellite phone (for communication and internet access)

- Spare engine parts

- Life raft, survival kit, and a locator beacon

- Medical supplies

- Soap and toiletries

- Reading material (because it's a long journey)

Before embarking on your sailing trip from California to Japan, find a trustworthy friend or relative to check in with along the way. Report your position to them twice a day every day, and instruct them to call authorities if they don't hear from you in a day or so. This means your contact on shore is never more than half a day or so away from your last-known position.

Sailing Route From California To Japan

Japan offers some of the most unique and remote sailing destinations in the entire world. However, it's a long way from the continental United States and one of the longest sailing journeys you can make without going through the Panama Canal. Here's an outline of how that journey may look, along with where to stop for supplies and rest along the way.

Pacific Ocean Sailing Hazards And Conditions

The pacific ocean is known for its vastness and warm temperatures. Unlike the Atlantic, you're not likely to encounter freezing Gaels or weeks of inhospitable and stormy conditions. However, there are a few times a year when the Pacific Ocean can get hazardous, namely during typhoon season.

The Pacific typhoon season varies between locations but usually runs between April and December. Typhoons are hazardous because they are hurricane-type storms with huge waves and wind. These tropical cyclones can cause extreme conditions and hurricane-force winds that span hundreds of miles, and they should be avoided at all costs.

Typhoons, like hurricanes, are extremely dangerous but highly predictable. Modern meteorological instruments and methodologies make it possible to see typhoons many days before they bear down, and most sellers can avoid them without trouble as long as they plan wisely and monitor storm reports.

Precise navigation and adequate experience are key to a successful long-distance voyage. A simple mistake on a chart can leave you miles off course, especially if you don't have a high-quality GPS aboard. Additionally, a GPS should never be a replacement for a traditional chart. Always mark your position at least twice a day on a paper chart while using a GPS. It's also helpful to learn traditional navigation tools in case your GPS fails.

Islands Between California And Japan

Some of the best experiences on Pacific sailing voyages happen along the way, as Pacific islands have some of the best scenery and culture around. There are several popular stops along this route, and most major islands have full-service marinas and supply distributors for food, water, and parts.

Hawaiian Islands

The first and most popular destination along the way is Hawaii. This island state requires no passport for Americans and is home to some of the world's best resorts and marinas. Additionally, virtually any repair can be performed on a sailboat at one of the state's many boatyards.

Hawaii is a great destination because it's roughly halfway to Japan. From the California coast, the closest Hawaiian Island is about 2500 nautical miles away. The waterways between Hawaii and the mainland are well-traveled and relatively safe, as typhoons never occur in this area. Additionally, you can take advantage of reliable westerly trade winds, which stall out just before the islands.

There's a wealth of knowledge and experience about the trip from California to Hawaii. Thanks to reliable trade winds, many sailors simply pole out the jib and keep the course straight.

Islands of Micronesia

When sailing to Japan, you'll pass briefly through Polynesia en route to Hawaii. After a few days of travel, you'll enter a region of the Pacific known as Micronesia. This region is more prone to typhoons than the northern part of Polynesia, but it's also home to several safe harbors.

There are many islands in Micronesia. Some of the most popular destinations for sailors are the Marshall Islands (the closest to Hawaii) and the Mariana Islands. These small island nations are home to marinas and supply depots, along with some beautiful coral reefs to explore. Stopping first at Marshall and then at Mariana breaks up the trip nicely—and Japan is the next land destination.

Preparing Your Sailboat To Sail From California To Japan

Preparing your boat is one of the longest processes you'll undertake before your trip. The vessel will be your home for up to two months (or more) and should be in excellent mechanical and physical condition before departure. Always change your engine oil and stock extra, along with spare parts such as belts and filters.

Additionally, take some time to check your plumbing and electrical systems. Make sure your lights work and keep extra bulbs, fuses, and hoses on board. Clean your fuel tank and freshwater tank, and have the black water pumped before departure. You won't need to use the black water tank once you're far enough out to sea, but you will when approaching ports.

Inspect your standing rigging and stays, and replace any aged or worn lines. This is essential, as a broken stay can spell disaster at sea. Additionally, repair any cracked or suspicious fiberglass while in your home port—it's easier and cheaper at home. We also recommend replacing your electric bilge pumps, as these can fail under heavy use.

How To Choose A Sailboat

If you're set on sailing to Japan, but you don't have a boat, here are a few considerations. Most monohull sailboats 40-feet and longer can safely make this journey, provided they're designed for bluewater sailing. Alternatively, a catamaran or trimaran can increase the comfort and speed of your journey, sometimes cutting the arrival time in half.

A large monohull, ranging from 40 to 50 feet in length, can be acquired for between $20,000 and $60,000 in turn-key condition. Smaller monohulls, in the 30 to 35-foot range, have made the journey before and usually cost a lot less. Catamarans are universally expensive and will cost several times more than a suitable monohull.

The main things to consider when choosing a sailboat are seaworthiness, accommodations, and condition. The best boat for you may be totally different from the typical blue water cruiser. As long as your boat is safe, reasonably large, comfortable, and has enough room for provisions, it can be used to sail from California to Japan.

Related Articles

I've personally had thousands of questions about sailing and sailboats over the years. As I learn and experience sailing, and the community, I share the answers that work and make sense to me, here on Life of Sailing.

by this author

Destinations

Most Recent

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

October 3, 2023

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

How To Choose The Right Sailing Instructor

August 16, 2023

Best Sailing Destinations In BC

June 28, 2023

Best Sailing Charter Destinations

June 27, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

June 15, 2022

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies. (866) 342-SAIL

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

For customers outside Japan

Boat export.

Boatflow aims to be the largest site in Japan offering used pleasure boats, sailing yachts, PWC, jet-boats, oversized work boats, patrol boats, speed boats, research vessels, and catamarans. directly from their owners.

Boatflow team of marine professionals will eagerly assist export buyers worldwide in purchasing the vessel and handling inland delivery and export formalities.

Boatflow will arrange inland transportation from anywhere in the Japan to our packing facilities or origin ports and help you safely and securely purchase and deliver a boat of your choice.

SHIPPING METHODS

Boatflow offers complete yacht transport logistics options which include domestic boat hauling by truck to loading ports, building a custom cradle to support yachts in transport, arranging loading and discharge operations with stevedores and load masters.

Boatflow offers several different shipping options, depending depending on the size of the vessel, desired destination and timetable required. These options include:

General Cargo, Deck Cargo

Vessels are carried on the deck of the ship.

Roll-on/Roll-off (RORO)

Ro-Ro vessels have built-in ramps which allow the cargo to be efficiently "rolled-on" and "rolled off" the vessel when in port. Available for either boats shipped on trailers or cradles to most worldwide destinations."

Flat Rack platforms

The Flat Rack platforms are regular shipping containers which have no tops or sides and give more flexibility for vessels with greater height and width dimensions up to 40ft

40ft high cube containers (sideways or straight-on)

Depending on make and model, many boats up to 28ft long with beam up to 8.6ft can be loaded sideways safely on custom built cradles into containers while narrow-beam boats can be loaded straight-on

Ask a question

Enter Your Full Name Here

Enter Your City Here

Enter your phone number here

Enter your email address here

Would you like to ask a question, make an offer or request specific information...

Office location

Mobile, Whatsapp, Viber : +81-80-3124-2233

Email : igor@boatflow.jp

Skype : boatflow

Office : +81-54-291-4075

Fax : +81-54-291-4076

Legal information

Registered name:BOATFLOW, LTD Registration Number:Shizuoka Prefecture Public Safety Comission No. 491150197200

Japanese fishing boat runs aground in The Noises, Hauraki Gulf

Share this article

Authorities are working to bring a commercial fishing vessel to port after it ran aground on rocks in the Hauraki Gulf in the early hours of this morning.

The Chokyu Maru No.68, sailing under the flag of Japan, has been identified as the vessel involved and has 27 crew members on board.

No injuries have been reported, police said.

Speaking on behalf of the Harbourmaster, Auckland Transport’s media liaison said the vessel was heading into Auckland when it got into trouble at The Noises about 3.42am.

“We have not identified any oil spillage,” the liaison said.

Troubled vessel visible from Waiheke

“There are 27 crew [members] on board and they are all safe. The Harbourmaster’s team is onsite at the moment and two tug boats are on the way to remove the vessel.”

That was expected to take place about 1.30pm when it is high tide.

Residents on Waiheke Island have reported being able to see the vessel.

A local whose house looks north, towards the Hauraki Gulf, said: “In the bright sunlight [this morning], it is easy to see the vessel aground.”

He whipped out his Samsung cellphone and zoomed in on the boat to get a closer look, he said.

Members of the Harbourmaster, Coastguard and the Police Maritime Unit were quick to respond to the scene early this morning, in a bid to offer any help.

A member of another boat crew travelling nearby said they saw the fishing boat involved overnight.

”It’s come up on the rocks last night,” he told Newstalk ZB.

Police say they were notified that a commercial fishing vessel had run aground around 5.35am.

Late this morning, Sue Neureuter - custodian of The Noises - said the fishing vessel has since been refloated.

Neureuter understood there was damage to the bow of the vessel, but not the hull. She also thanked the authorities who responded to the incident.

AT said the vessel is being assessed for damage and, if given the all-clear, it will be able to resume its journey to Auckland.

The Chokyu Maru No.68 measures 48.19m in length, 8.6m wide and was built in 1988. Its port of registration is recorded as Muroto, Japan.

The Rescue Co-ordination Centre NZ has been approached for more information relating to the incident.

Latest from New Zealand

SH1 near Taupō closed after logging truck rolls

“No injuries have been reported,” police said.

Te Papa's defaced Treaty of Waitangi exhibition to be removed next week

Black Power veteran illegally 'squatting' on coastal land eyes another round in eviction fight

Victory for Pākiri mana whenua may be shortlived as fast-track approval bill offers miners another chance

Kids missing school to feed families

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Japan is no stranger to the world of sailing. When it comes to investing in a sailboat, you might want to consider Japanese sailboat brands because their boats offer just the right mix of technology and ergonomic design, which is what sailing enthusiasts look for in boats. From Mitsubishi to Ishikawajima-Harima, and Yamaha, there are many ...

Find Sail boats for sale in Japan. Offering the best selection of boats to choose from.

1957. International Marine building wooden boats based on Herreshoff 28-foot design. Okamoto Shipyard building 35- and 40-foot wooden ketches designed by Garden and commissioned by Hardin. 1958. Clair Oberly founds Far East Yachts, builds wooden versions of the Alden/Oberly-designed Mariner 31 and Garden-designed Mariner 40. 1960.

Mr. Seizo Ando of Aomori, Japan building an inshore fishing boat. Ando was the author's fourth teacher, and together they built this boat in the summer of 2003. Ando is fitting the keel and the first plank by running a series of saw cuts through the seam, an essential technique in Japanese boatbuilding. Photo by Douglas Brooks.

The following is the list of ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy for the duration of its existence, 1868-1945. This list also includes ships before the official founding of the Navy and some auxiliary ships used by the Army. For a list of ships of its successor, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, see List of active Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force ships and List of combatant ship ...

Motorized yachts are more common than sailboats in Japan with 11 powerboats listed for sale right now, versus 2 listings for sailboats. Yacht prices in Japan. Prices for yachts in Japan start at $100,000 for the lowest priced boats, up to $6,500,000 for the most luxurious, opulent superyachts and megayachts, with an average overall yacht value ...

The naval history of Japan began with early interactions with states on the Asian continent in the 3rd century BCE during the Yayoi period.It reached a pre-modern peak of activity during the 16th century, a time of cultural exchange with European powers and extensive trade with the Asian continent. After over two centuries of self-imposed seclusion under the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan's naval ...

Buy sailboats in Japan. Sailboats for sale in Japan on DailyBoats.com are listed for a range of prices, valued from $98,570 on the more basic models to $531,000 for the most expensive. The boats can differ in size from 12.19 m to 52.12 m. The oldest one built in 1993 year. This page features McConaghy, Alubat, Farr and Najad boats located in ...

In fact, they don't need to caulk new wooden boats at all due to a technique Brooks explains in detail in his new book, straightforwardly entitled "Japanese Wooden Boatbuilding." This is the story of the author's apprenticeships with Japanese masters, the last of their kind building unique traditional boats of endangered styles.

The rigging is made up of masts and sails which differentiate the various types of sailboats. The most common types of rigging are: masthead and fractional sloops, cutters, ketches, schooners and yawls. Find sailboats for sale in Japan, including pricing info, photos, and more. Find your boat on iNautia!

Maruko-bune. A maruko-bune ( 丸子船) is a type of traditional wooden sailing boat, the design of which is unique to the Lake Biwa region, Shiga Prefecture, Japan. The name is related to the rounded shape of the hulls in cross section, " maru " meaning round in Japanese. Maruko-bune were in regular use in the Edo Period transporting cargo on ...

Buy a boat from Japan - Boatflow providing a large variety of pre-owned boats in Japan and assist you with export to your destination country. ... directions_boat Search by Category. MOTOR BOATS 1804; SAILING YACHTS 127; ENGINES 54; JET 23; FISHING VESSELS 4; COMMERCIAL VESSELS 3; turned_in Popular Brands. MOTOR BOATS. 7. MOTOR BOATS. 7.

Buy a Boat or Yacht in Japan. Search the world's most accurate database of yachts and boats for sale in Japan, Asia. YATCO 's yacht and boat listings feature a wide selection of new yachts, used yachts and boats, including mega yachts, superyachts, sailing yachts, sailboats, sportfish boats, powerboats, trawlers, catamarans, and more.

New Japan Yacht Co. - Japan, company New Japan Yacht Co. Ltd. Boat models/ranges: Lune de Mai, Loup de Mer, Libeccio, Esprit du Vent, Vent de Fete, Cybelle, Mira Belle, Love me Tender. Manufacturer: sailboats (sailing dinghis/sailboats without berths, sailing yachts/cabin boats) built since 1969.

General Terms. Wasen 和船- meaning "traditional Japanese boat". A general term for any wooden boat of Japanese style. Amibune 網船 - a general term for a net fishing boat. Bezaisen 弁才船- a class of large coastal transport, of which there are several types. Gyosen 漁船 also Tsuribune 釣船 - fishing boat.

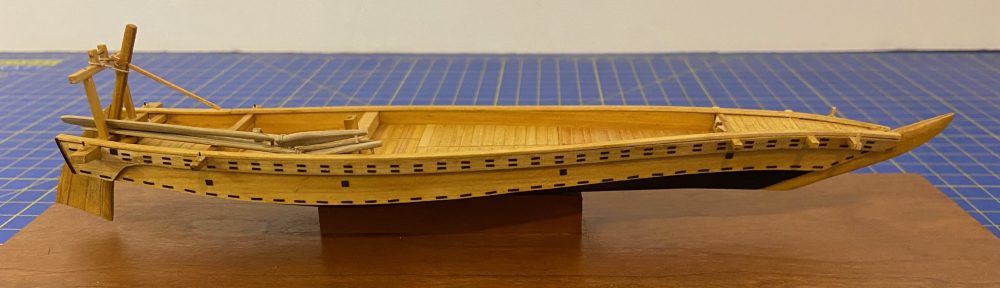

Japanese Sailing Ships and Boats. IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER. 8th Century. 47-01 Kentoushi-Sen, Period: 8th century, Scale: 1/60, Scratch-built by TAKANARITA Kiyoshi . 15th~16th Century. Kenmin-maru Period:15th Century Scale:1:30 Scratch-built by TAJIMA Isao (The Rope Hiroshima)

Recommended for sailboats experts 3 250,000. View More. Crewed Charter ... The 10th annual Aki Matsuri Japanese Festival made its center-strip debut in Las Vegas on Saturday, Oct. 26 at The Park and New York-New York Hotel & Casino with an immersive all-day celebra 08/11/2019

SAILBOAT listings: Click on the images below to view a sample of the current BoatWorld SAILBOAT listings: Buy New and Used Yachts, Dinghys & Sailboats Direct From Japan. Source From Auction, Dealers, Wholesalers and Private Sellers For Maximum Choice & Best Prices.

Find Boats for sale, Japan's finest boat to offer worldwide, Sell your boat, research boats, boating news, blogs, boat loans, insurance, transport.

Japan remains an obscure sailing ground, despite being a highly developed country. Nick and Jenny Coghlan enjoyed a surreal cruise. Preparing for Sailing in Japan. E verybody had warned us that the Japanese love paperwork. So as Bosun Bird, our Vancouver 27, worked her way northwards through the islands of the western Pacific, every so often we'd crank up the Iridium satphone to find out ...

How Far Is California From Japan? A single, non-stop sailing trip from California to Japan is about 5,150 miles. This is a considerable distance for a sailboat to travel and will likely take a month or two to achieve. Assuming your sailboat travels at 7 knots, it'll take around 30 days.

24m Patrol Boat. $170,000 Japan. 26m Patrol Boat. $185,000 Japan. 161m 930pax Roro. Japan. 46m Roro For Sale By Tender. Japan. 30mtr 245pax Cat Ferry.

BOAT EXPORT. Boatflow aims to be the largest site in Japan offering used pleasure boats, sailing yachts, PWC, jet-boats, oversized work boats, patrol boats, speed boats, research vessels, and catamarans. directly from their owners.

A commercial fishing boat has run aground. Tuesday, 16 April 2024. ... Japanese fishing boat runs aground in The Noises, Hauraki Gulf. NZ Herald. 15 Apr, 2024 09:42 PM 2 mins to read.

Chinese boats are also swarming around islands occupied by the Philippines and conducting patrols within its waters. China has long had a contentious relationship with countries in the South China ...