Attainable Adventure Cruising

The Offshore Voyaging Reference Site

- The Garcia Exploration 45 Compared to the Boréal 47—Part 3, Hull and Build

In Part 1 and Part 2 I compared the rigs, deck layouts and cockpits of the two boats. If you have not yet read those articles, please do so now with particular attention to the disclosure that the series starts with.

Now let’s move on to the hull design and build.

Scope Of The Article

Since I have never even seen a Garcia Exploration 45 out of the water, a lot of what follows is based on images I found on the internet using Google Image Search . Point being that those thinking about a Garcia need to dig deeper.

The good news is that I did connect with a Garcia dealer to get some questions answered—the factory ignored my inquiries.

Also, since Garcia, unlike Boréal, provide almost no information about how their boats are built, I will be writing about how the Boréals, and aluminum boats in general, are built, and then suggest things that those interested in buying a Garcia, or any aluminum boat for that matter, should check out during a factory visit before purchase.

Hull Design

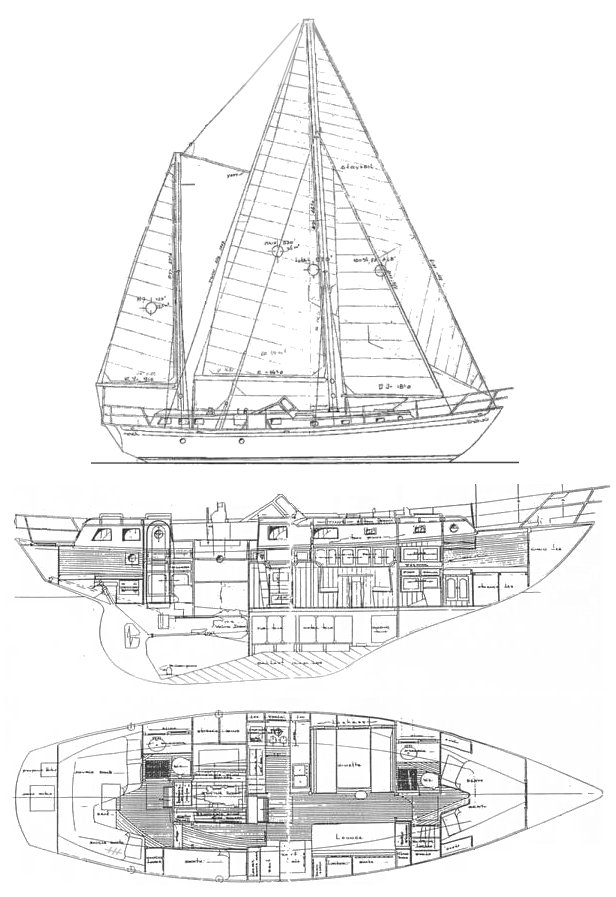

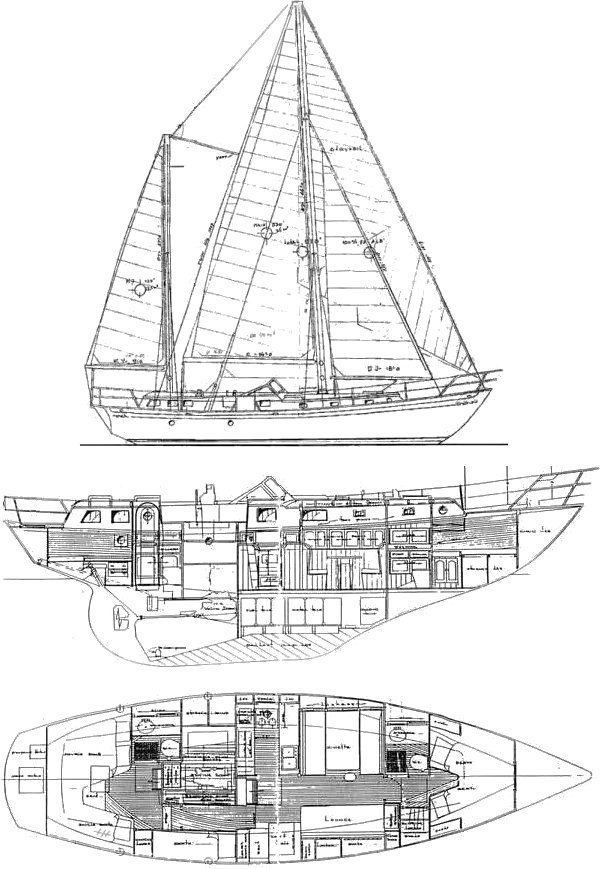

Both boats are members of the “internal ballast with centreboard” class of boats that the French builders have long executed so well, with examples like the older Garcias and Ovnis to be found in every port around the world where cruising boats gather, and in a lot of remote and hazardous places, too.

(By the way, this is a different approach than lifting ballasted-keel boats like the famous Pelagics or Seal . Both approaches have benefits and tradeoffs, but for these articles, I’m not going there.)

Love or hate them—I fall into the first group—these boats have a proven track record of safe voyaging over many decades, a track record that puts to bed any worries about their relatively low static stability due to relatively high positioning of the ballast.

Login to continue reading (scroll down)

Please Share a Link:

More Articles From Garcia Exploration 45 Compared to the Boréal 44/47:

- The Garcia Exploration 45 Compared to the Boréal 47—Part 1, Introduction and Rig

- The Garcia Exploration 45 Compared to the Boréal 47—Part 2, Deck and Cockpit

- The Garcia Exploration 45 Compared to The Boréal 47—Part 4, Inside Watch Stations

- The Garcia Exploration 45 Compared to The Boréal 47—Part 5, Interior, Summary and Price

Hi John I’ve enjoyed all 3 articles, and am left wondering why anyone would choose the Garcia over the Boreal. I’d be interested in hearing from one of the experienced owners (Goss et al) just why they decided on the Garcia. One point that you haven’t addressed is “beauty”, and that is another point where the Boreal wins hands down. I don’t wish to hear that beauty is a subjective concept. ? The forward raking windows of the deckhouse on the Garcia are not only ugly, but strike me as being unseaworthy. I’ll never own a Boreal, but they remain the only reason that I occasionally invest in a lottery ticket. Yours aye Bill

There’s been a trend to more use of chines these days even in racing yachts. Do Boreal have an explicit rationale for using chines?

I am sure there are plenty of contemporary accounts of the performance features of chines but Chapelle in The Search For Speed, said that any angular form in a hull which crosses waterlines flow would be a source of resistance. It is unlikely that the chines in a yacht would always present a line parallel to flow lines so you would expect more resistance in a chined hull?

Of course, they say chined hulls will definitely produce more resistance to rolling, a positive factor. Do you have any view on this?

I believe chined hulls are also easier to construct as no panel forming is required and that panel forming in materials like aluminium weaken the metal. Do you have any view on this?

Hum, most of that is above my pay grade to be sure about, but as far as I know chines don’t really make a lot of difference one way or another in performance.

As far as I know, the key benefit is that it’s, as you say, way easier to build a chine boat. That said, I don’t believe that the forming required to build a metal boat without chines makes a lot of, or probably any appreciable, difference strength wise because most of the strength of an aluminium boat comes from the frame, not the plate. (The exception is boats built with the Strongal method.)

I would also doubt that chines would make an appreciable difference to rolling, but I could be wrong.

Hopefully Jean-François will come up with some thoughts on this.

My understanding is that chines make sense on wide, light, downwind flyers for which they assist directional stability when heeled (compensating somewhat for this type of hull’s tendency to round up and/or depress the bow when heeled); support more powerful rigs by increasing buoyancy (at the expense of increased surface area which doesn’t matter once you’re planing); and reduce water-separation drag at planing speeds. None of these benefits seem to apply to an expedition yacht. At lower speeds the extra surface area will hurt performance. Combined with the higher-drag keel-box this might see the Boreal fall behind a Garcia in light conditions. Perhaps the chines make a metal hull more robust.

Hi John, Hi Henry,

As you say Henry, chine hulls are easier to construct (and repair) and require less tools. Also because of the chines (almost) nothing is spherical, everything is cylindrical in the alu work. This means that we only bend the alu plates in one direction and that we can have all plates arriving at ther yard pre-cut to the exact size as a big puzzle/mecano.

But you have to see the history of Boréal : Jean-François Delvoye designed what he thought was the ideal simple live aboard alu centerboarder for his family and build it himself. The personal project was not meant to become a yard with now more than 60 boats sailing all over the world. When you design a boat you are going to build yourself you see things in a different way. You much more think “how am I going to build it”…

This said different naval architects and yards use chines for different reasons. One of the common reasons on some cruising boats is because using chines can allow to increase the inside space…

Unlike Mr. Squire seem to think there is no automatic link : chines – more wet surface – slower boat (in light airs). In fact, sometimes it is even the opposite and the chine allows to narrow the width at or just above the waterline…

Everything is a compromise but the Boréal is narrower at the waterline than the Garcia. (the price for that we have less internal volume). She is also lighter. This a theoretical explanation why one boat sails better in light airs. In practise, on the water : It is a recurrent comment from all who have tested the Boréal in light airs to say how amazed they are by its velocity. This has been the case since the very first testsail with the very first Boréal with Daniel Allisy, chief editor of Voiles & Voiliers. We have sailed side by side upon several occasions in light airs and we know for a fact what is the reality on the water… One should try for himself both boats in indentical conditions, much more convincing than any explanation…

Hi Henry and Jean-François,

I can confirm that the Boreal is way faster up wind in light air than I expected, see further reading.

I agree with you wholeheartedly re combining fiberglass structural pieces with aluminum, as on the Garcia. Boats from Allures, which also now belongs to Grand Large, feature aluminum hulls with all glass decks. To me this negates what I see as one of the main selling points of a metal boat: a unitary hull-and-deck structure with minimal possibilities for chronic leaks. At some point the joint on an aluminum/glass boat is going to cause very annoying problems that will be a pain to resolve.

As to twin rudders versus a single rudder: the rudder on the Boreal is quite short and helm feel while steering is not great. It is not one of those boats that is a “joy to steer.” I noticed this the very first time I test-sailed one with JFE and accepted it. As a cruiser I spend little time hand-steering in any event. The Garcia, by comparison, with its twin rudders, has better helm feel and is more rewarding to steer. In this sense, as you suggest, the Garcia might seem preferable to those who are not planning to sail in high latitudes. I have sometimes wondered if Boreal should offer twin rudders as an option. Discussing this once with JFD I found he has strong opinions, as he once lost a rudder on a twin-rudder boat.

In spite of having a short rudder, the Boreal is remarkably forgiving in sudden strong gusts of wind. The rudder does not suddenly stall, leaving you with no steering, as sometimes happens on performance-oriented boats with deep high-aspect rudders when they are over-powered and laminar flow over the rudder foil abruptly ceases to exist. On the Boreal the rudder loads up gradually, always maintaining some grip, and you have time to make adjustments. Ease the main or drop more of your aft daggerboard to leeward. The motion of the boat in gusts meanwhile is likewise very muted and reassuring.

Jimmy Cornell told me when I sailed with him that he had to lobby Garcia very hard to get those partial skegs on the 45’s rudders. He wanted full skegs. Frankly I’d like to see a full skeg on the Boreal’s rudder. It would have prevented the problem I had with my rudder coming loose en route from Bermuda to New England and would give me much more peace of mind when running through the lobster pot strewn waters of Maine. In that the Boreal’s spade rudder is not really balanced in any meaningful way I see no downside to a skeg. It would only add strength if a growly bit of ice or whatever did jump behind the keel box and strike the rudder.

Like you I see no downside to the hard chines on the Boreal. Some people will tell you they actually increase initial stability, which is why presumably we see them on more and more fiberglass boats these days. Building a metal hull with hard chines is certainly simpler and less expensive.

On the keel box, or whatever you want to call it: one of the great features of the Boreal is that it heaves to extremely well. You can do it with the centerboard up or down. With the board up she makes a lot of leeway and leaves a nice slick to windward that theoretically should tame breaking waves. With the board down she does a fairly good job of staying put. My current theory is this attribute is due to the keel box having all its working area aft, that this helps her keep her nose up to windward.

I never had a chance to heave to on the Garcia, so I cannot compare. The keel box on the Garcia, as you say, is smaller than the Boreal’s, but its area is also aft, so it may also heave to well.

I have intentionally grounded out my Boreal a few times now. The wide foot of the keel box and the lower ballast inside the box makes her very stable indeed when dried out. Grounded out on a slope once (not on purpose) and had no problems.

I have not grounded out on the Garcia, but did participate in hauling out Jimmy’s boat in a yard in Panama. If you look at the boat in profile there’s an awful lot of upward slope from the back of the keel box to the bow. More than on the Boreal. My guess is on a hard surface she would dry out bow down with her rudders well clear.

Like you, I know nothing of the scantlings on the Garcia. As you say, on the Boreal they are formidable. You could throw the boat off a three-story building and I suspect it would suffer little or no serious structural damage.

I had not realized the ballast on the Garcia is cast iron. A bad idea. I wish European builders would stop doing this. It is, as you say, a particularly bad idea on an aluminum boat.

I’m wondering now what they used for ballast on older pre-Grand Large Garcias.

Hi Charlie,

I guess helm feel is pretty subjective, but I was truly amazed at how good the Boreal felt going upwind with the lee board down (see further reading). That said, as you point out, what really matters on a cruising boat is how well mannered she is and here the Boreal seems to be great.

Not at all sure about the adding a skeg. The gap between the keel box and rudder is pretty small and I’m guessing that even partially filling that with a skeg would be a big efficiency hit on what is already a quite small rudder. Also, I wonder if balancing the rudder would not be a negative because it would reduce the feel even further.

Great to hear that the Boreal heaves to well, and that you guess the Garcia would too. I have been asked this question about the Boreal several times, but have just not had the experience (first or reliable second hand) to answer it, so very good to have a fill on that. (As I think you know, Phyllis and I are huge fans of heaving to.)

And I’m totally with you on the folly of iron keels. I know lead is expensive, but as a percentage of the total cost of a boat I still think that using iron comes under “spoil the ship for a ha’p’orth of tar”. Ditto mixing GRP and aluminium.

Once again, thanks for sharing your experience with the two boats.

It seems to me both these broad sterned yachts are problematic, perhaps even relatively unseaworthy given the compromises made. And the fact that they are both centreboarders exacerbates the problem – a single deep centerline rudder can’t be used. The respective builders have adopted different solutions and I would suggest neither of them are appealing, to me at least. Better to have a boat with balanced heeled waterlines in the first place and avoid heeled bow down trim. Would you agree?

Hi Henry, I sincerely wonder why you think that… The theory that in heavy seas lifting your centerboard will avoid you to be tripped over is now a proven concept. (It was before Boréal started building boats) Again theoretical approach versus reality : The Boréal has a proven track record. Our owners (and ourselves) have taken our boats to the wildest places on earth… Yes, just as every other boat, the boat is a compromise and yes, there is room for improvements but in this category I wonder which kind of boat would be more seaworthy…

Jean-Francois,

Firstly, you will note that I used the qualifier “relatively”. I did not say the Boreal is unseaworthy. And I was referring specifically to the use of lee boards.

It seems to me any unprotected hull appendage is a potential liability even if it is sacrificial and replaceable particularly one that, from the accounts described in this article, has a significant bearing on the steering qualities of the yacht. I can imagine situations where the loss of this steering ability could be disastrous (say, short handed, beating off a lee shore in a boisterous sea, inshore, lee board sheared off by an uncharted rock , requiring immediate remedial action – could a damaged lee board get stuck in its sleeve?).

I look at the Boreal’s lines and interior, it is love at first sight, but then one begins to think about the compromises that have been made (every boat is a compromise as you well know). For me, I would rather have a yacht with a soundly constructed deepish centerline rudder behind a longish not so deepish keel with a lump of lead attached to the bottom of it with the keel attached to a hull with well balanced heeled waterlines. If this meant giving up excellent broad reaching ability and a nice big fat stern lazarette, then that’s the compromise I would make. We are all different.

And just for the record, I think chines are well worth considering in an aluminium boat.

And benign skidding factors do not only belong to a centreboarded yacht. High freeboard, moderate beam and shallow fixed keels can also fit the bill.

Bottom line, you don’t want a lifting keel shallow draft boat, like a Boreal or Ovni, and that’s fine. That said, given the record of these boats, saying that they are not seaworthy, even “relatively” is simply ignoring the facts. Also the Boreal sails fine with no dagger boards so there would be no worries of not getting out of a tight spot if one was sheared off.

I agree that balanced lines for and aft, particularly healed, are important, and I too was worried about this when I first saw the boat. But have a look at the pic at the top of the post and you will see that the Boreal accomplishes this well and when I steered the boat up wind my worries evaporated. The fact that the boat steers herself up wind in puffy conditions proves that the ends are well matched beyond any doubt. And note it’s not just me saying that she steers so well (see further reading). As to seaworthiness, the record of Boreals, Ovnis, and older Garcias is second to none, so I just can’t see it being an issue. Have a look at the Boreal record of cruising tough places that I detailed in part 1. I don’t think there is any other production boat that comes even close.

You are misrepresenting my comments. I was careful to add the “relatively” qualifier for a reason. I don’t question the seaworthiness of the yachts. The yachts obviously perform well in real world conditions but require extraordinary steering capacity to do this which opens them up to certain vulnerabilities. Any wide sterned boat is going to trim down by the bow when heeled and lift a centerline rudder out of the water somewhat. I was merely making the point that the compromises made in this case do not suit the risks I personally would be prepared to carry. You said yourself in one of your Boreal sailing tests that “she did seem a little squirrelly up wind in the puffs and lulls” until the lee board was immersed and then she performed flawlessly. It’s not surprising on both counts. And this is in 12 knots of wind – the sea state would have been relatively benign. Put yourself in an extreme situation, short handed as hypothesized above – I would not want to deal with that situation ever if I could avoid it. It’s only a hypothetical possibility but real enough if it happens. In your review, you mentioned that “closer examination shows that Jean-François Delvoye has used considerable flare in the topsides aft so that the actual water plane is quite symmetrical fore and aft and further, as the boat heels, the water plane remains that way. ” Fair enough, the waterplanes might remain symmetrical but she will still trim down by the bow pulling the centreline rudder out of the water to a degree. (It seems to me the waterlines remain symmetrical because stern volume is truncated by considerable rocker aft.) The fact that extraordinary steering measures have been taken suggests there is an issue. And the Garcia’s twin rudders are just as vulnerable, and perhaps relatively (there’s that word again) more than the Boreal given the Boreal has a protected centerline rudder, albeit it relatively (just can’t seem to get away from that word) short one because of the virtually non existent keel. The lack of a fixed keel enhances downwind performance and allows her to beach. More compromises which I personally would not take. Compromises which others obviously prefer.

You are assuming a lot that is simply not true about the Boreal. For example Colin just sailed a brand new one 20 hours from France to Falmouth up wind into F7 conditions. He tells me the boat performed flawlessly. And few people, if any, have his experience in different types of boats. As you point out, she has a lot of rocker aft, and that’s exactly why, together with flare, she does not stuff the bow. It’s also why she has less room in the aft cabins (more on that soon). The point being that Boreal have leaned toward seaworthiness and good sailing over accommodation in every decision because the boat was designed to take their own families to challenging places, not please a market. So just assuming she will exhibit the same problems as boats with a lot of volume aft is flawed logic.

Look, the boat you describe as the one you want is exactly what I have and have sailed for nearly three decades and over 100k miles. I love that boat type too, but to make unfounded accusations about another design that is different like saying that she is “relatively unseaworthy”, against the boats we like, is simply being closed minded, particularly given your limited knowledge of the boat in question and the track record of said boat.

You are still misrepresenting my comments. I have no where judged the performance of the Boreal. As you correctly point out I have no experience of her. I do have your reported comments though.

You say the Boreal does not trim bow down. If this is so why are there extraordinary steering arrangements on the boat (both boats in fact) without which the boat does not perform flawlessly (according to your comments)? These days most if not all modern broad sterned production yachts have twin rudders. Unapologetically not interested! 🙂

All I am saying is that these steering arrangements could possibly be (whether probably is another matter) compromised at critical times. These are risks I would not be prepared to take myself. That’s all I am saying. I wish you would get this. Others on the other hand accept and value the offsetting performance features.

This is yacht design. C’est la vie!

What I’m objecting to is your base assumption that the boat trims bow down when healed. That’s not what I observed and further if she did that would imply a buoyancy mismatch and that in turn would result in a tendency to round up in puffs, and we know from several different sources that that’s not the case. The point being that the Boreal may have a reasonably wide stern at deck level (although modest by modern standards) but that is offset by hull flare and rocker to result in a hull without buoyancy mismatch at the angles she operates at.

After I sailed on the boat and found my worries about the stern seemed to be unfounded, I had a conversation with her designer who was kind enough to explain how it all worked. I learned a lot more than I would have done if I had let my assumptions based on my own boat plug my ears and blind my eyes. And further, the Boreal hull form was tank tested to make sure that they had this, and other stuff, right.

You are also assuming and saying that the lee boards are there to compensate for bow down trim when healed. That’s not what they do. Rather they compensate for the small rudder size to obviate the need for twin rudders on a shallow draft boat or the complexities of a lifting rudder.

Point being that you are building an entire argument on a flawed assertions. As the moderator of this comment stream I can’t allow that to stand.

You have also repeatedly stated that the Boreal will be less (relatively) seaworthy than a keel boat. But that again is an assumption, not a fact. The fact is that the Boreal will have better dynamic stability than your ideal boat or the boat I own (scaled for size). And the latest science shows that dynamic stability is as, or maybe more, important than static.

Here’s a radical idea for you: the Boreal (and Ovnis and Garcias) may even be more seaworthy in a storm than the boats you and I favour. Not saying that’s true, but it’s definitely a possibility. And one I’m open to in my continuing quest to learn more about safe offshore sailing. You might want to read this to understand that these things are not as simple as you are stating them: http://marine.marsh-design.com/content/dynamic-stability-monohull-beam-sea

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that the Boreal approach is better than what you like, but to argue against it from flawed assumptions simply makes no sense. Better to just say that the boat does not work for you and leave it at that.

One think I have learned in 50 years of offshore sailing and 15 years of running this site is that there are a lot of different ways to come up with a good and safe offshore boat. And further, that assuming that everything other than the type we favour is flawed is a great mistake that prevents us from learning and growing our understanding. Sure I have made that mistake in the past, but I try hard to be open minded and, after reading an important book on decision making, I have been trying even harder…

Thanks for taking the time to explain the bow trim issue in more detail. I take and accept your correction of my comments. As I mentioned in an earlier comment it is plain that volume has been taken out of the stern with the deep rocker. Given that and the other measures taken to offset the broad stern, I accept that the hull has been designed to be balanced when heeled. Given that, I can then accept that the reason for the lee boards is solely to do with the shortish rudder.

However you are still misrepresenting my comments on the seaworthiness of the Boreal. As I have repeatedly explained my concern is with the unprotected lee boards. This is my particular paranoid fear, if your like. For me this is a real risk. Some people are prepared to wear this risk, being compensated by other performance factors inherent in the Boreal’s design. I did not say the Boreal is unseaworthy. With lee boards in place it performs as required. If the lee boards were sheared off in a critical situation there might be difficulties. You yourself have said the yacht behaved normally with the lee boards down and not so much with them up and that was in what I would call in benign conditions.

Regarding the Boreal and its drop keel and skid factors. I have not said the Boreal is unseaworthy because it has a non fixed keel. I have never been in a situation where the yacht I was on was threatened by huge breaking waves. (The worst I have been in is in Bass Strait in an F10 storm with 30ft waves steep as walls coming at us , but surprisingly they were barely breaking.) So I really cannot speak to the situation. All I have to go on is the advice of people like Steve Dashew (“Surviving the Storm”). And I don’t question the experience of people who have survived encounters with big breaking waves in non-fixed-keel boats. Given Steve’s advice and my other paranoid fear of not having a lump of lead attached to the bottom of a keel under my feet, then that’s another preference I would have. Others can differ, that’s fine with me. So please do not misrepresent what I have said.

That’s fine, as long as we have the bow down trim issue sorted, I’m happy to agree to disagree on the level of vulnerability that the boards represent.

On the rudder skeg: I think there’s room to fit one in there. And I wonder if it might not improve the rudder’s effectiveness (see comment below re the single daggerboard ahead of the rudder on a Garcia Passoa).

All my previous bluewater boats had rudders attached to either keels or full skegs. I was biased in favor of this. But I did read an awful lot about how a properly done spade rudder can be very solid, and have talked to many I respect who believe this, so I swallowed my bias in choosing a Boreal. Now I’ve had a problem with my spade rudder, early in the game, so my bias is swelling again.

Yes, I hear that, nothing like having a nasty problem at sea, and steering issues are very high on the nasty scale, to kick in the paranoia. That said, I’m still reasonably sure that adding a skeg ahead of a rudder is a pretty big hit to lift and assuming I’m right (by no means certain) that would say that adding a skeg would have reduce the effective area of the rudder. That said, I’m talking at least 150% of what I know here.

Maybe Jean-François has some wisdom on this? Or anyone else who really understands how rudder hydrodynamics work?

By the way, the bearing problem you had could be solved once and for all with a Thordon bearing that is installed after being shrunk with dry ice. We changed to one of these some 10 years ago and it’s absolutely secure without the use of set screws or sealant. We just gave all the relevant dimensions to Thordon and they made the bearing a press fit to the tube ( slips in when cooled with dry ice) and slip fit to the shaft. https://www.thordonbearings.com/marine-markets

Fascinating! Thanks for this tip on Thordon bearings.

One other thought on heaving to that struck me after my last comment: surely having a lot of area aft on the hull would be more a negative than a positive since that would move the centre of lateral resistance aft of the centre of effort of the rig and hull windage? The way I thought about this was to imagine a boat with a dagger board forward. Putting the board down would tend to make the boat sit with her bow further up in the wind. So conversely, say putting a Boreal lee board down would tend to bring the stern up in the wind and be a negative. Assuming I’m right on this, that might imply that the Garcia would have more trouble keeping her bow up, particularly with the board up, since she has no keel box.

And further, having sailed centre board boats quite a bit, both inshore and offshore, I would caution others (I’m sure you are aware) that if it’s gnarly leaving the board down will decrease both boat’s capsize resistance.

I know exactly what you are saying here and that thought has definitely occurred to me. As I said my thinking on this is only theoretical. I come to it asking the question: WHY does the Boreal heave to so well? There’s certainly no daggerboard or keel area forward to keep the bow from blowing off. That she will heave to with the centerboard up is what made me start thinking about the area in the box keel aft. Which got me thinking about other boats I’ve had. One that heaved to very poorly, with a full keel cut well away both fore and aft, and another that heaved to very well, with a full keel cutaway forward but not aft. I can’t offer a hydrodynamic explanation of why this would be so. There may be other features in the hull shape that help here. The relationship between the sails and underbody obviously is important.

Steve Wrye has a lot to say about heaving to in a Boreal. Perhaps he might chime in here if he’s paying attention to us.

Hum, beats me too. Still the key point is that the boat does heave to well, which is great and is a huge check box for me on the list of what makes a good offshore boat, particularly for short handed crews.

Hi Charles and John, sorry to be so late to the table I just completed a 7 month delivery of a Boreal 44 and have not had the time to partake in this discussion. Maybe I can help here with a few observations, one on heaving to, another on stability and lastly on going to weather on a Boreal. I’m not expert in design but like John I have been sailing a lot of years and over time I have learned a lot through observation. So here are my opinions with actual results on a Boreal. By the way I do not own a Boreal anymore I am totally free of having that bias.

Heaving to; When I received my Boreal, hull # 13 in 2013 I was a bit concerned that the Boreal would not heave to. Having spent a lot of time with the two owners of Boreal I could not get much info on heaving to from them. They told me that one owner did heave to with great success but that’s all they could tell me. They were of the mind if I remember right that running down was the way to sail in those situations one would heave to in. In the Canary Islands waiting for hurricane season to end we often took the Boreal out and tested many ways to sail her, it was a totally new concept for my wife and I to sail such a boat as we have only owned more traditional CCA boats. As for heaving to we did so on a day with 25 to 35 kts winds and really lousy close 2 meter seas. I started with two reefs in the main, the boom down center of boat and the centerboard all the way down. Forward a block on the windward side mid cleat and a sheet to the stay sail run through that block and sail pulled all the way over to windward. Also helm all the way over to windward side and tied off. Just like the way we did it on our more traditional boats like the Mason 44. I was amazed that the Boreal worked just like the Mason. The Boreal sailed forward at about one knot and the bow was at about if I can remember right 45 degrees apparent. Very comfortable very normal and very much like any good CCA blue water designed boat would heave to. But then for the hell of it I started playing around with different ideas and things became even better. I started to raise the centerboard up a bit at a time and each time I did so the boat slowed down moving forward and she came up into the wind a bit more. By the time I had pulled the centerboard fully up and took some of the helm to windward away the boat was going about a half a knot backwards and the bow pointed as much to weather as 17 degrees apparent. Just like I’ve read about in the old full keel boats of long ago. What a beautiful slick to windward. Never have we had a more comfortable heave to in 40 some odd years of sailing. I think Charles is right about the keel it is just big enough when the centerboard is all the way up or close to being up the boat will not slide side ways much and move in a bit of backward direction.

Stability; the Boreal is very stable and drier than any boat I have ever sailed. In one of the earlier discussions on Boreal’s back a few years ago I told the story of being hit on the beam by a standing breaking wave at two in the morning while I was on watch. That breaking wave had so much force in it and it was only about 15 or so feet high. But never have I heard a louder noise and a boat be shaken as much for a very brief time. It did break over just about the entire boat up to as high as the boom and filled the cock pit full. The Boreal did slide side ways and the windward side of the boat, (port side) the breaking wave side seemed to be a bit lower than the side of the boat one would expect to be lower if a boat was being tripped by the wave. It was only a few seconds for all this to happen and we were back on course doing 7 KTS with the auto pilot on. If that had been our beautiful sea worthy Mason 44 I have no doubt that we would have tripped and put the starboard spreaders in the sauce with a complete stall out nose up into the wind.

As far as needing the lee dagger board down for going to weather it sure makes for a nice ride with great control of steering. But what I have found with the Boreal no matter what point of sail you are one keep the right reef in the main. If I keep the boat as flat as possible and not heeled over more than 8 degrees, I like less a lot less if possible. I can sail the Boreal just fine without the lee dagger board down if i do not have too much sail up. A lot of times the boat will sail faster without a lot of sail that makes it over powered. Going to weather with lee dagger board down proper sail management in 25 kts of wind and lousy seas I have sailed with Boreal with Colin on board at about 55 degrees apparent and was able to keep speed up. Pretty damn good for a centerboard boat. Just keep your sails where they work best and the boat does its job very well. One more thing, I don’t think Boreal is perfect and I tell them that often. But in over 40 years of sailing I have never met a boat building company that takes the time to listen as well as Boreal does. JFD and JFE go out of their way to help all the Boreal owners with any problem they may have. I also think JFD is quietly one of the greatest blue water / expedition sailboat designe ever. Having sailed with Garcia owners and hung out with them I know Garcia is not so bad at helping an owner out but in no way do they compare to Boreal for service and caring. The Garcia is a fine bluewater boat but can’t touch the Boreal for a blue water plus an expedition boat for the demand that its owners put on the Boreal be it in the higher lats, the atolls of the Caroline’s or the jungle rivers of the Amazon and Borneo. Cheers Steve and Tracy.

Thanks very much for that update. Particularly good to hear that the Boreal will heave-to without forward motion. As Phyllis and I found out the hard way, pretty much any forward motion makes heaving-to ineffective and in fact dangerous: https://www.morganscloud.com/2013/06/01/when-heaving-to-is-dangerous/

Your comment about the steering feel is interesting. Having never sailed one of these boats but finding them very interesting(and not currently in the market for a boat so this is completely academic), steering is one of the things I had been wondering about. I am one of those people who loves to steer and if I am not needed for something else and the engine isn’t on, I go for the tiller/wheel rather than a book and sometimes steer for hours at a time. From afar, it would appear that it is a good thing that the prop is so close for maneuvering under power. But it also makes me wonder if the big fixed props I often see in pictures on these boats really hurt steering performance under sail due to no part of the rudder really being clear of disturbed water.

I think that a lot of whether or not you would like steering a Boreal would depend on what your bench mark is. I came direct from Morgan’s Cloud a boat that is great fun to steer up wind, and was still pretty impressed once the lee board was down, and even with the boards up I did not hate it. What I really wonder about would be steering off the wind in big breeze. Here I think the Boreal might even be more fun than the boats we are used to since with the board up the centre of lateral resistance will be way aft. I’m thinking that the same techniques I learned years ago in high performance dinghies in big waves might work well and produce big grins.

Any experience/wisdom on that Charlie?

And I agree, I have never understood why anyone who really likes to sail would saddle a boat with a fixed prop. As a past PHRF handicapper I know just how big the hit is.

On steering off the wind: doing so on one of these French centerboard boats is a blast. It’s one of the reasons I like them. Still my experience on the Boreal is that you still have to be careful not to oversteer. As I said earlier (in a previous thread), it helps to have both daggerboards down. Then you are riding, as I like to think of it, a big French metal surfboard. I had a chance once to steer downwind for a long time in strong conditions aboard an older Garcia, a Passoa, and my vague impression is that it steered better than the Boreal. It was a long time ago so this may not be a reliable memory. Interestingly, that boat also had an aft daggerboard, but only one, right in front of what was also a short centerline spade rudder.

That’s good to hear. I can certainly see that over steering would be a mistake, but then that’s the same with most any boat that really gets smoking off the wind. Years ago, in the early days of really fast off wind boats like Merlin Stan Honey told me they were actively recruiting 505 sailors to drive in the TranPac because they instinctively knew how to keep the boat under the sails whereas those drivers more used to keel boats would wipe out regularly.

Hi John and Charlie,

I have very little experience in dinghies in actual seas, most of my small boat big seas adventures happened in kayaks but what you describe intuitively makes sense.

What actually makes a boat have good steering feel is very hard to define to me. If I had to list my favorite 10 boats to steer that I actually had experience with, 2 boats over 100′ would be on there despite big boats having a reputation of no feel. Both boats are slow to respond by the nature of small rudders and enormous inertia but they are also predictable and really reward a good helmsman. I have also steered even more expensive yachts than these which are faster but no fun to steer. Big rudders alone are certainly not the answer although too small is definitely bad. Balance, predictability and feel would probably be my top criteria but I am not sure even that is right. For a cruising boat, our current boat is a lot of fun to steer, combined with the build quality (in a relative sense, there were still plenty of issues) it is what sets the boat apart from many boats of a similar era in my opinion.

John’s comment about keeping the boat under the sails is spot on but I find that many people don’t know how to apply it, oversteering seems to be the norm. When I get on a new boat to me, I first try to steer as minimally as possible which allows you to see how the boat handles on its own and then you can start to try to do small proactive rudder changes to improve from there. Growing up, I spent a lot of time on boats that are along the lines of NY32’s and they are really great teachers of minimalist steering which becomes necessary on really large vessels. Talking to some people who are accomplished on sportier boats and have crewed Dorade recently, they have commented that they had to learn to anticipate more and steer less and that it made their sportboat helming better too.

By the way, my thought on the fixed prop had nothing to do with speed, it is that a rudder that is shallow does not have a big amount of area running in relatively undisturbed water below the prop disturbance. I can’t actually quantify this but it is clear that a fixed prop creates quite disturbed water, although a keel does too so it may not be as big an effect as it might otherwise be.

I agree, it’s very hard define what factors make a boat fun and easy to steer. Kind of like the old saying about porn “hard to define, but I know it when I see it”. That said, I do think that there is one factor that boats that are fun and easy to steer share: symmetrical water planes for and aft, that stay that way when the boat heals.

And yes, that was my worry about fixed props too and I think the turbulence is way worse than the keel. I can still remember sailing my old Fastnet 45 with a fixed 3 blade prop for three weeks while waiting for a new MaxProp and after removing a folding prop (long story about why that sequence of props). I could actually feel the difference on the helm from the prop turbulence and the negative effect in speed and pointing was amazing. The Fastnet was never a good boat to steer (terrible directional stability) but with the fixed prop it got way worse.

Hi John I’m currently looking at a semi-expedition design boat with one of those skeg designs where the skeg swoops down to the lower rudder bearing leaving what is something like a very large aperture for the prop. The prop is directly in front of the rudder— should be great for managing prop wash at low speeds. I built a similar design years ago but never was able to test it under sail. Have any readers had enough experience with this particular configuration to let me feel confident that changing to a feathering prop will cure the problem of rudder stall and turbulence affecting the helm feel and autopilot performance? As I recall the Fastnet 45 had a lot more separation between the prop and rudder but still had a similar problem?

Hi Richard,

I can’t be sure, since, as you say the Fastnet is very different. That said, I’m pretty sure that a feathering prop would be a fix. I base that on the Paine Justines which are configured the same way. I understand they steer very sweetly, are fast (for type) and most (all?) have feathering props.

Hi Charlie I remember well your glee while steering the Passoa 47 Che Vive downwind in a gale, passing dozens of other boats in the Marion-Bermuda race. I enjoyed it too.

Having now sailed our own Passoa 47 over 40,000 miles, I think that the single rudder with the centreline daggerboard is one key to the easy steering. Our Raymarine autopilot never draws more than 5 Amps, and hand steering is easy Like the Boreal, the Garcia rudder is shallower than ideal for hydrodynamic efficiency, but is well protected I think that the skinny stern of the Passoa (skinnier than the Expedition or the Boreal 47) is a great asset, although it makes for skinny bunks The one time we sailed alongside a Boreal, we were a knot faster and pointing slightly higher, but that was just one set of conditions. 15 knots, moderate chop in the Hebrides

I agree. The bottom line is that displacement boats, like your Passoa, that are symmetrical fore and aft sail and steer better.

As an Allures owner I think I can speak to the Garcia bottom plate thickness as both the Allures and Garcia are fabricated at the same yard – which we visited. Although the Allures has significant compromises (and some benefits including being less costly), I am pretty sure the hull plate thickness and structure matches the Garcia. The bottom plate thickness of the Allures is 10mm. Thicker plate is used in some high load areas including the transom (16mm) and keel skeg (12mm).

One benefit of the twin rudders that was not mentioned is that they are set up to accommodate redundant autopilots. Not sure how easy this would be to accomplish on a Boreal.

In terms of the ballast material, I suspect in either case if the full penetration welds of the 10mm plate have failed, and sea water is getting into the ballast compartment, one has a major problem. Not sure epoxy encased iron or lead would make the problem smaller or easier to fix. I believe this kind of failure is very unlikely. I guess with iron one would see staining and know there is a problem before it spreads. Hard to imagine this happening on any of these boats and low on our worry list.

Hi Charlie & John Looks like those who actually have time in a Boreal don’t find the smallish rudder a problem. But in the spirit of solving a problem that doesn’t exist (LOL) I should point out that there are several ways to design rudders with variable draft. For example, if the rudder is transom hung, (as are many Open 60’s) then it is quite simple to design it with a sacrificial breakaway lower section or a hinge latch held in place by a hydraulic cylinder with a pressure “fuse”.

Chines vs radius; Ironically the only Garcia I’ve been aboard was a Passoa specially designed for Antartica. The bottom plate was 12mm, and the radiused garboard plating a single 8mm sheet nearly 50′ long formed on a giant roller. In the hands of Sr. Garcia the hull was a flawless work of art. Fair as a mold tooled fiberglass boat, with no welding distortion like heavily framed aluminum boats.

But he is no longer with us, the company that carries his name is a conglomerate, and boats are built in factories. In the hands of anybody but a true aluminum master, chines make all kinds of $$$Sense.

Yes, the old Garcias were loverly. I was drooling over one this summer hauled in Maine. Note that I did mention the Ovni rudder, but do be aware that this design has not been without problems (I have this direct from an owner) so I guess I just like the simplicity of a single part rudder. Also the Ovni uses a flat plate rudder to make it all work, a big efficiency hit.

Hi Richard, John as I guess you’re both aware, our Ovni 435 has a ‘split’ rudder, with the upper section fully supported by a skeg and the lower section liftable via a hydraulic pump. This has a lot going for it, not least as it allows the rudder to be lifted (as well as the centreboard) for beaching horizontally when on the bottom. It also (as with the board) incorporates a failsafe ‘rupture’ plug on each circuit, that will burst on major impact to save the various parts of the system from damage. This works, as I can attest having hit a log, which burst the plug and allowed us to install a new one and be back in action in 5 minutes. Given the severity of the impact, I don’t doubt that we would have suffered major structural damage to the rudder otherwise. The single spade rudder on the Boreal works well, and is well protected by the keelboat ahead of it – totally acceptable, in my view. Finally chines – some people don’t like them aesthetically, and I can see that, but – they offer solid protection from bumps when coming alongside, help reduce rolling at anchor, aid directional stability (albeit not by a very great deal) and – my favourite – when the boat is heeled on the breeze, let the boat heel until she settles down on to the chine and stiffens up noticeably – so you don’t ‘sail on your ear’, so much. Obviously, these attributes apply to multichined designs, less so for single chined designs. After many miles in both round bilged and multichined designs, I’m a convert. Best wishes Colin

Thanks for the fill, particularly on your experience with chines. I had not thought of the stiffening effect at all.

We had a very minor quibble with J-F on the design of the boreal chainplates/tangs. The tangs for the 4 lower shrouds (attached through the deck to hefty frames) are vertical. The loads along the shrouds, however, are not vertical (since the shrouds are in front of and behind the mast). This introduces some eccentric loading on the stainless steel strapping that holds the toggle at the end of the shroud – with the outside of the toggle being pulled over the end of the tang.

J-F pointed out that these attachment points are hugely over-designed and there’s never been a problem – which is completely true. We pointed out that it would still be better if the load ran straight through the tang with no bend – which is also true. In the end, they kindly agreed to fabricate the tangs for our boat at the required angle so the loads run true.

Sounds like a good modification, thanks for the tip.

First post on this august site! I have also lusted after a Boreal for a while and have found the analysis very interesting. The only thought I have had with regard to the spade rudder. I have always had a prejudice about unsupported rudders but am happy to be corrected – it is a prejudice after all. Could a compromise be to have a simple plate running from the bottom of the keel to the bottom of the rudder. The rudder could have a simple shoe. This would provide additional protection in that it would prevent ropes and such like from riding up and snagging on the rudder. This would also make it more difficult to foul the propeller. What do people think?

As with other commenters, my thoughts are totally academic pending a lottery win. 🙂

I have to admit that I too had a prejudice against spade rudders, but, as I say in the post, over the years I have come to believe that as long as the the rudder is really well built, and the rudder post bracing inside the boat is done right, that the benefits of spade rudders are pretty compelling. That said, the idea of in some way closing the gap between the keel and rudder on the Boreal is certainly attractive. However, such a structure would, I think, have to be pretty massive if it were going to get even close to matching the strength of the keel box and existing rudder, remembering that this is a boat intended to dry out. And that, in turn, would produce a fair amount of drag and probable reduce the efficiency of the already small rudder.

So given that the rudder is already well protected behind the keel box, and further protected when the board is down, and it’s leading edge is swept back enough that I think it would shed most debris that got past the keel, I think the downsides of adding structure would outweigh any benefits.

Bob Perry’s latest commission ( the Carbon Cutters) uses exactly such a strap to connect a longish fin keel to the rudder. However I suspect the real reason for it was to satisfy the client’s insistence upon a full keel boat and Bob’s desire to design a boat with a nice helm feel and a turn of speed. It’s a funny old world when owners insist upon building their old fashioned looking custom boat out of pure carbon fiber just because they struck it rich in the Seattle market bonanza. (Regardless of the fact that it probably creates a worse boat for this application) And even stranger, three best buddies decide that they have to have identical copies in spite of the fact that there is no mold for the construction.

My experience with full skeg mounted rudders on most fiberglass and cold molded wood boats is that the rudder shaft serves the function of supporting the skeg rather than the other way around! It also prevents using balance— area forward of the shaft axis to lighten the forces on the helm and reduce loads on the autopilot or wheel.

With metal boat construction it is quite easy to build a skeg strong enough to provide substantial protection to the rudder. Combine that with a partial skeg and a rudder designed with a sacrificial lower 1/3 * and you can have the combination of an optimal rudder hydrodynamic shape and a rudder that is still functional after a conversation with a grey whale.

*(glass layup over a red cedar core on the lower 1/3 with a zipper line of small holes in the core at the break point for example) ** Another benefit of a partial skeg is that it is inherently much stiffer than a full length one, and with a bearing mounted at the lower end can massively contribute to the stiffness of the rudder shaft itself. ***For a metal boat designed to dry out, the benefits of a sacrificial lower rudder section are null and void!

Hi Richard, John and all, I am not sure what is meant by Bob Perry’s “strap” from keel to rudder, but: As someone who, when underway, is fine keeping a good lookout for other boats, whales and the like, but absolutely abhors the effort, concentration, and anxiety of sailing in areas where fish/lobster/crab pots are strewn, I have spent considerable time imagining a remedy. I have a conservative fin keel and a skeg (full length) hung rudder (Valiant 42) and I seem to get hung up once a year or so. I have wondered about having a light line going from the aft/ bottom end of my keel to the bottom of the skeg of the rudder. It would not need to be a very strong line as its job would be to direct pot pennants along the line so they are more likely to clear the prop and the rudder. Clearly this would need to be a break-away line. If broken, the worst mischief I could see would be to get around the prop, which, if light enough, should just break it or get cut with the line cutters. More likely it would just stream aft behind the skeg This is such a simple idea; I am sure someone has done it and already discovered some fatal flaw. Is this the same idea as the “strap” mentioned? Thanks for your thoughts. My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick If you look carefully you can see the connector between the fin keel and the transom hung rudder in this series of photos. The keel itself is interesting. When you walk up to it it is monstrous in surface area. Reminds me of one of those giant sunfish one occasionally encounters, but very thin. The carbon keel cavity is filled with lead. I don’t think it would be possible to build an integral keel this narrow except as a one-off from a male mold. If you are going to build a one-off carbon boat on the West Coast Jim Betts is your guy. http://www.bettsboats.com/yachts/current/perry43/

ps Check out the official displacement: 35,600#. That is a lot of Carbon! Even if 12-13,000 of the total were lead.

Hi Richard, Thanks. That is one sweet set of pictures. I am glad I am not looking for a new boat in which to go wandering widely or my first-born child would be in jeopardy. Is the strap only to keep pot lines/debris from getting in the aperture and getting hung up (similar to my thought for the break-away line) or is it (maybe also) structural and providing some fore and aft support? Thanks, Dick

Hi Dick My best guess is 2++ million each for those boats. A bargain considering how much it costs to send your firstborn to Harvard. For that price you could have a Boreal 47 built with a custom ballast compartment to store all the leftover gold bars saved, and be prepared for SeaSteading after the Collapse.

From talking with Bob I know that the client was a long term Cape George 36 owner. The design brief was for a Cape George 36 with a full keel, transom hung rudder, and split cabin trunk lacking headroom in the mast area, only bigger and more expensive. My guess is that the “strap” was employed so it could be called a full keel boat and make both the client and designer happy. LOL

Nice looking design. Seems to me the aperture strut is a great idea, protecting the rudder and propeller.

Here she is scooting along in what seems a moderate but stiff breeze and no waves at hull speed:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HLR5VM1FGbQ

It’s interesting to note how she rounds up immediately there is a gust (the boat can be seen to heel a touch more) despite the long keel.

Interesting discussion. I am the owner of the Boreal 47, Curlew, that did the crossing from France to Falmouth this year mentioned by John, skippered by Colin (thank you, Colin!) in demanding conditions, so I am not a disinterested party. I can certainly confirm that the boat performed flawlessly on the trip, and on the subsequents legs to Crosshaven and then up the west coast of Ireland.

We spent this summer with Curlew in Connemara, on the western edge of Ireland, putting on many miles, often in bad conditions. Although not exactly Patagonia the area is exceedingly remote and the few other yachts you see are typically en route between Scotland and France. If you get into trouble, you are on your own. Rescue may take a considerable time. The weather is demanding with high average wind speeds coupled to a constant large swell.

A few observations.

Being able to pull up safely on a beach, previously viewed as nice, I now see as essential. In remote areas the water quality is usually high and you get rapid shellfish build-up. Cleaning the bottom, checking anodes and greasing the folding propeller are all nice things to be able to do but if something significant below the waterline goes wrong you have to be able to address it yourself. Diving is always inefficient, sometimes dangerous and never inviting in these waters. Additionally, in remote areas the few piers and harbours mostly dry out, so being able to handle that greatly increases the number of places where you can seek shelter from bad weather.

Secondly, even in remote areas there are crab and lobster pots everywhere. Accurate GPS now allows fishermen to put out huge numbers of these. The limited yacht traffic is seldom considered and buoys are found even in passages between islands or rocks. Twin rudders add greatly to your exposure to this risk. It is also useful to bear in mind that charts are updated on a frequent basis only where there is traffic. If you are off the beaten track this is not the case and although charts will be internally consistent, meaning that visual bearings are accurate, the longitude reference is often slightly out, so at close quarters GPS will not be accurate. In short, sooner or later you are going to clip a rock. I am much more comfortable thinking about this – it has yet to happen – with my single rudder behind a substantial keel box than I would be with twin rudders.

Great and very useful real world report, thank you. I totally hear you on the benefits of drying out. I can’t tell you the number of times I have wished I could easily do that as well as the number of times I have wished I could get up some snug shallow creak when bad weather was bearing down.

Hi John Really enjoying your articles and comments on them with regards these two yachts. I was just wondering if it would at all be possible to hear your thoughts or anyone’s with regards to another yacht builder I have been looking at from Holland who also manufactures aluminium yachts ….. specifically there 45 Pure from KM yachts. I have often read and seen mentions of other yachts in your articles and subsequent comments but have not seen a mention of KM. Many Thanks. Also really looking forward to article 4.

I have not put any time into investigating K&M so there’s not anything useful I could say. That said, the designer is well known and well respected with huge experience.

Hi Andrew and John, In 5 yrs of poking around Northern Europe, there was only 1 boat that consistently caught my eye: it was the Bestevaer series from K&M. There were a number of boats that I thought well done in the traditional manner (Rustler/Rival/Bowman) but the Bestevaer boats really seemed at casual glance to be pushing into the nice combinations of live-ability, easy handling, go anywhere safely, low maintenance boats. There was that and the owners we occasionally spent time with were among the more experienced and knowledgeable skippers. Not sure why they are not better known. My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

KM are building Skip Novak’s latest Tony Castro designed Pelagic:

http://www.kmy.nl/yachts/pelagic-77/

If you are serious about the K&M and looking for a second opinion I would highly recommend hiring Colin to report on the boat for you. His fee will be a small fraction of what the boat will cost and worth every penny: https://www.morganscloud.com/services/consulting/

Hi John and Dick

Thank you for your information. In the past I have also been very interested in both the Bowman and Rustler yachts as well, however more recently have been gravitating towards the aluminium yachts especially with there strength and versatility with the shallow draft options.

Regards Colin I will keep this under careful consideration.

Hi Andrew, You are welcome. For jump-starting what can be a long, impressive, and expensive the learning curve and for making more likely you will start out with a boat that checks your particular boxes, I can’t think of a better guide than Colin. Let us know how you make out and the decisions you make. My best, Dick

The Bestavaer 45 is indeed an impressive looking yacht. I’ve long admired them. Quite different from the Boreal in terms of design. More expensive too.

I can report I had a chance to compare performance one-on-one with a Bestavaer 45 I saw in Cape May, NJ, last year. The Bestavaer left first; I left soon afterwards on my Boreal 47. We were both sailing north, downwind, singlehanded, under working sails poled out. No spinnakers or drifters or anything fancy. My Boreal quickly overhauled the Bestavaer and it was three miles behind us when I turned off into Atlantic City.

For whatever that’s worth.

Skip Novak is building his third Pelagic 77 at K&M.

I agree with at least one of John’s comment that potential Garcia Exploration buyers should actually talk to Garcia owners, particularly those who have sailed with the boat in high latitudes! I would also encourage them to speak to a few Boreal owners as well. I have…. Best Regards Chris de Veyrac S/Y Haiyou Garcia exploration 45

Hi Chris, I appreciate you talked to Boreal owners and then you bought the right boat to better satisfy your needs. I only discussed it with Jimmy Cornell, but he might be biased ?. Happy sailing! Alex.

Hi John It’s impossible to compare any two designs in depth without developing opinions. (AKA biases or conclusions.) If those opinions are fact-based they contribute to the analysis. On the other hand if they are mere personal preferences they may be equally important, but of little use to others.

It is my personal opinion the Garcia 45 is ugly and the styling makes it look like it is radically trimmed bow down. This opinion has little to do with how it performs or whether another owner will fall in love with it. On the other hand the disadvantage of twin rudder designs in ice or log filled waters is a question of fact.

I recently did subcontracting work on an $18 million dollar ultramodern home with over a million dollars of glass in its walls and an inverted roof that permanently leaks (Thanks, Famous Architect). If I were to receive it as a gift with the condition that it could never be sold I would bulldoze it and build a 1200 sq foot log cabin in it’s place. Bias or a belief that design must fit the surroundings and environment?

I have found your series of articles comparing the Boreal and Garcia Exploration very interesting. We bought an Allures 45.9 new in September 2017 and are now in New Zealand having sailed over 20,000 NM in the last two years or so. Our boat is of course from the same stable as the Garcia and shares many features (and there are also a number of significant differences also between our boat and the Exploration 45). I think that it would be useful for your to consider a follow-on article that compares and contrasts the after sales experience that a sample of Boreal and Garcia owners have enjoyed (or not enjoyed). The first year or so of ownership of a new boat is a time when minor and sometimes major issues need to be resolved. During our travels these past two years we have chatted to many purchasers of new boats from many different makers and the after sales experience seems to have varied dramatically. Once a boat leaves the factory, there should be an ongoing supportive relationship between the builder and the owner. Resolving issues in far flung parts of the world is never easy but good support helps a great deal. I look forward to your thoughts.

Julian Morgan S/Y A Capella of Belfast.

Sure that would be great if it could be done, but the problem is how would such a survey work in practice?

For example how would we get a list of buyers and even if we could, how could we assure that the builder had not cherry picked the list?

The other problem is that boat owners that have had a bad experience are loath to out the builder for it because they are afraid that this will make their relationship with the builder worse than it is, and/or reduce the resale value of their boat. I know of one major builder who is famous for punishing owners who say anything bad about them by withdrawing support—I can’t publish a name because no one will go on record, so my liability would be horrendous. And I can’t tell you the number of times readers have written to me to complain about boats but then don’t want that publicized.

And finally, to do this right would be hundreds of hours and many dollars in communications costs, so how would that be financed? And then what about legal liability and cost of insurance against litigation if a builder felt that they had been unfairly singled out and could prove that the survey results were inaccurate? (One of our biggest costs is our journalism liability insurance, but I just know the underwriters would up the premium big time if we told them we were going to take this on.)

The bottom line is that such a study, to be useful and relatively safe from litigation, would need to be rigorously done, not just casual antidotal interviews.

All that said, how has your experience been with Allures and Grand Large?

Also, do you have any thoughts on something I may have missed about the fibreglass deck advantages. I have always been very hard on this, but always interesting to hear the opposing view from someone who has the miles you do on the boat.

Hi John (and Bill),

My comments certainly do seem to have got under your skin, and I’m sorry for this. Nothing is gained by putting people’s backs up. That was not my intention. This is the only site of this type that I visit, nor do I use social media. In consequence I don’t know the meaning “trolling” (in this context) or “forum games” (images of toga-glad children playing hop-scotch in the market place come to mind, tho’ I pretty sure that’s not what you mean).

So, in the interest of righting the ship a little I would like to address my suggestion that the inclusion of non-dimensional ratios and form coefficients would have improved the content of this 2 boat comparison. John seems to have jumped to the conclusion that I was asking that this data be included in order to evaluate speed potential or prepare a VPP. Nothing could be further from the truth. Although helpful in comparing differing appendage (keel or rudder for example) designs on an existing hull and necessary for use in routing programs I personally do not find them particularly useful in evaluating an existing design.

I was suggesting that their inclusion because, taken as a whole, with a knowledge of the general type and style of craft that they pertain to and with some experience in evaluating them, they give the best indication of the designer’s intent and the type of vessel and its performance (in which speed is just one of many behaviors and properties) that is likely to result.

In my opinion a compiling of these ratios and coefficients and a familiarity with them is the single most useful thing that a prospective buyer of a sailing vessel can do to ensure that he selects a boat best adapted to his needs. I absolutely disagree with John’s statement that “a few ratios would tell us nothing about two boats this similar”.

In his reply to my comment John asks if I seriously expect him to collect such data and if I seriously expect the designers of the two boats to share it. I can’t answer the first question, not being privy to AAC’s resources but I would note that both sailing magazines and published books (see Bob Perry’s volume on his designs — chock full of this kind of info as well as lines plans) increasingly share this information. A very cursory internet search on the Garcia yielded D/L (208), SA/D (15.9) and ballast ratio (32%) data from a not altogether laudatory Yachting Monthly review.

As to designers’ willingness to share this data I think you might be surprised. As a young NA student I spent 4 years compiling such a data bank for designs that I admired. Among many prestigious designers who kindly answered my questions was the designer of Morgan’s Cloud. I still remember the pale blue airmail paper (it was a long time ago) on which his charming reply was printed.

I understand that AAC is John’s property and he gets to decide its content. My suggestion may not fall into his vision of the site, he may feel that it would not be of interest to the membership or that it would be impractical for any number of reasons. I offered it simply as one member among many as a way to further improve the site’s value to its readership.

Garcia specifically refused to give me any data on the design, other than the very scant amount published. As I wrote in the post, this made it impossible to make any meaningful comparisons since they don’t even specify the load state that the displacement applies to. Nor would they tell me if the SA was 100% fore triangle, which it should be, but often builders use the overlap of the genoa to make the boat look more powerful. As to the numbers in magazines, very often they are wildly out due to just these kinds of problems.

And I stick by my assertion that said ratios would not have been useful in comparing the boats since I’m fairly sure that they would be quite close, or at least not useful enough to justify the time and effort involved in deriving accurate numbers.

That said, I agree that ratios are useful for comparing different types of boats, but that’s not what this series was about. If I was writing an article comparing this type of boat to say a fixed keel boat like the Outbound 46, ratios would have been very useful and inaccuracies less of a problem.

Agreed that the classic ratios such as SA:Displacement are often wildly inaccurate in magazines and sales literature I dug into this deeply when designing a sail plan for Milvina, our Passoa 47, that was taller than standard. I calculated values for a number of well known boats, and when I found different results from publications, called vendors. I got a range of push-back but no solid info Sales/magazine info for most boats I looked at presented numbers more appealing than my calculations based on the boat’s dimensions

Yes, it’s very annoying since it makes it hard to come up with any meaningful comparisons and worse still it calls into question any comparisons we read about online or in magazines. The sail ratios are bad enough, but when we get into displacement it gets really murky. And even waterline length is pretty fungible since what really matters is effective waterline length when underway and the only way to derive that is a full hull image.

On iron vs lead ballast When Garcia was building our Passoa 47, I was keen on lead ballast, but ended up with iron for two reasons Firstly, my calculations showed that lead would lower the centre of gravity by only a few inches, because of the wide, flat shape of the ballast in centreboarders Secondly, Jean-Louis Garcia told me that he had trouble with a lead ballasted boat because it hit the rocks, leaked and was weeks in the water afterwards. Jean-Louis related that when lead, aluminium and seawater are together without oxygen the lead corroded rapidly and formed bulky corrosion products that pushed the welded top off the ballast enclosure A simple test I did with lead and aluminium showed rapid corrosion Jean Louis also related having repaired boats with iron ballast that had sailed for months with damaged, leaking bottoms and he had observed only a little corrosion The result was that we chose iron ballast, although we had been willing to pay for lead

That’s interesting. Based on your comment I took a look at the galvanic table and it is true that cast iron is closer to aluminium alloys than lead. I was surprised. Also the fact that Jean-Louis said this gives me more reassurance. I will think on it some more, but maybe change the article to reflect this.

Hi again Neil,

I just found a different galvanic scale that indicates the exact opposite: that lead is closer to aluminum than cast iron. Clearly going to take more research to get a definitive answer, even assuming that’s possible.

My key input was what Jean Louis Garcia told me. They had at least one rock battered Garcia in for repair on about half of my dozen visits to the yard, so he clearly had experience Concerning the galvanic table, remember that it is based on metals with oxygen around. In the case of sea water leaking into ballast, there would be no oxygen You have surely observed that the alloys used for yacht hulls corrode badly if seawater is trapped against them under a bolted on fitting I suspect this may explain the difference between the galvanic table and Jean Louis experience In my work as an engineer with industrial equipment corrosion, I observed that corrosion reactions in practice often differ from elementary chemistry

Protection of hull when drying out As you say, the solid keel in the Boreal protects the hull to some extent, but I am not sure the hull needs it. In our Garcia Passoa 47, the bottom is 10mm plate with a lot of ribs. In the integral fuel and water tanks, the anti-slosh webs are solidly welded to the hull, reinforcing it. In the ballast areas, of course the ballast back up the hull. I do not know how the current Garcias are built

One possible issue with the Boreal keel is that a boat dries out on a flat bottom, balanced on the keel as the tide slowly falls, then falls with a bang when the boat is fully dry. If the boat heels quietly as the tide drope, then it will not be too livable I think you are correct that Garcia owners perhaps do not dry out often. We have done it only a few times, once inadvertently. One Passoa owner we visited in Brittany keeps his boat on a mooring in a somewhat sheltered bay, where it dries out on a gravel bottom every tide. When we met, he had been doing it for years. I guess his boat has grounded more often than all the other Garcia boats put together

Experence has shown that the Boreals don’t fall off the keel box. It’s simply too wide for that. More here: https://www.morganscloud.com/2019/12/22/the-garcia-exploration-45-compared-to-the-boreal-47-part-5-interior-summary-and-price/comment-page-1/#comment-289259

I agree, with that kind of construction I don’t think you have a lot of worries drying out.

I was reading the discussion on the Boreal’s daggerboards with great interest, but did not really find answers to a few questions that arose. I saw that John and Henry had differing opinions on what kind of a problem losing a daggerboard might consitute. As far as I was able to follow the discussion, in lighter airs the lack of the daggerboards would require a bit more attention on the helm, but that seems like a very small issue.

I am wondering does anyone have experience in more demanding conditions? For example, how would clawing off a lee shore upwind in strong winds work if the boards were gone?

Has anyone tried raising the lee board when beating in a real blow?

Any other situations in which not having the boards would be a real problem rather than a minor nuisance?

Assuming that it would be a real problem in some situations, carrying spares might make sense. That brings up the question whether or not the boards are identical so that one spare could fit in place of either board, or are they mirror images so that both sides require a separate spare?

I guess the risk of losing both would be small, but the above has bearing on the costs of carrying the spare(s).

I don’t know the answers to these questions in detail, but Colin does, so if you are really interested in buying a Boreal, then it would be worth talking to him about this, and other factors. https://www.morganscloud.com/consulting/

That said, having sailed the boat a bit, and having talked to several people with a lot of miles in Boreals, I’m pretty sure that the boards are an added benefit, but not required for safe operation. Also, the last time I talked to Boreal none of their boats had suffered a board breakage.

If memory serves, the boards are identical.

https://youtu.be/WNVTFd4t_HE

Hi John, Boreal’s daggerboards can be broken as you can see on the n° 42 ep ” Bushpoint ” on You tube. It was last year on a Boreal 55 in the north of Norway. Even if it was not a great issue , it can happen. The owner fix it himself. My wife and I are looking to build a new boat to change our Ovni 43 and we ask Patrick Lenormand, the yard manager of NYS ( Caen France) to build it . We have chosen a Cordova 45 ( design of Jean-François André , well known french architect ) . His choice of a twin rudder system concern me . He said that he put two strong skegs welded on the hull to prevent any damage. My worry is also about the drag of these skegs in front of the rudders . I know that a boat is always a trade-off but I don’t want to make a mistake. It’s always a great pleasure to read AAC. Best regards, Françoise et Jean-Michel.

Hi Françoise and Jean-Michel,

That’s such an interesting question that I answered it as a tip: https://www.morganscloud.com/jhhtips/twin-rudders-have-no-place-in-the-high-latitudes-or-maybe-cruising/

- Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

Garcia Exploration 45 – Yachting Monthly review

- July 24, 2014

Finding a new boat to sail the Northwest Passage might not appeal to most people, but most people aren't Jimmy Cornell. Graham Snook went to test the boat Jimmy commissioned - the Garcia Exploration 45.

Product Overview