What is a Sloop? Definition, Types and History

A sloop is a type of sailboat that has a single mast and a fore-and-aft rig.

Sloops are a type of sailboat that has been around for centuries. They are known for their versatility and ease of handling, making them popular among sailors of all skill levels. Sloops have a single mast and a fore-and-aft rig that allows for efficient sailing in a variety of wind conditions, making them an excellent choice for both cruising and racing.

Sloops are designed to be easy to handle, even for novice sailors. The simple rigging system means that there are fewer lines to manage than on other types of sailboats, which makes it easier to focus on sailing the boat. This simplicity also means that sloops require less maintenance than other boats, which can save you time and money in the long run.

One of the great things about sloops is how versatile they are. They can be used for everything from day sailing to long-distance cruising to racing. Their design allows them to sail efficiently in a wide range of wind conditions, from light breezes to strong winds. This versatility makes them an excellent choice for sailors who want a boat that can do it all.

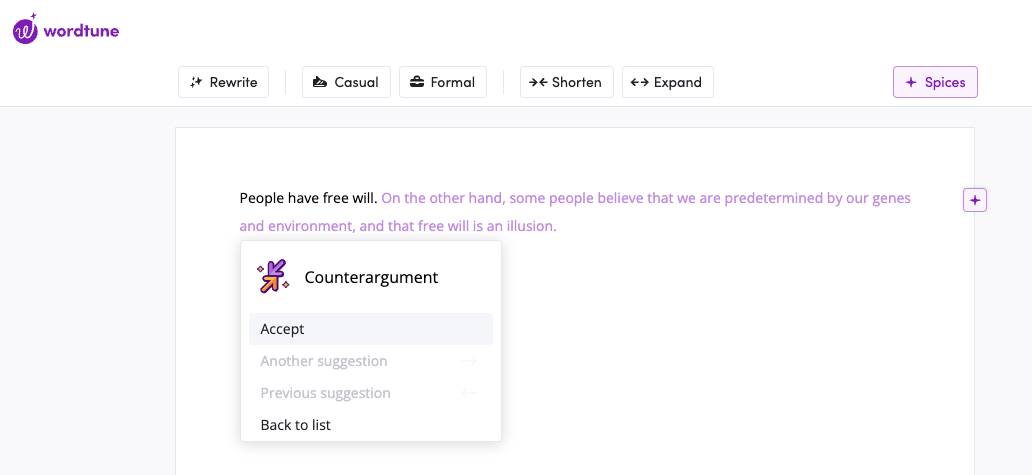

The Versatile and Popular Sloop Sailboat Rig

Single mast and fore-and-aft rig.

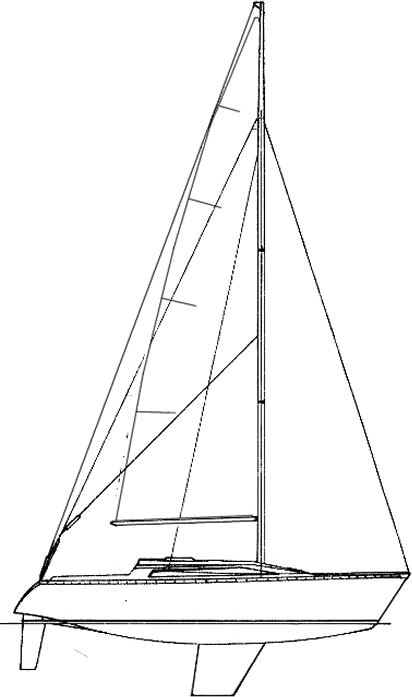

A sloop is a type of sailboat that has a single mast and a fore-and-aft rig. This means that the sails are positioned parallel to the length of the boat, making it easier for sailors to control the direction of the boat. The simplicity and versatility of the sloop rig make it one of the most popular sailboat rigs in use today.

Mainsail and Headsail

The mainsail is the largest sail on a sloop, and it is attached to the mast and boom. It provides power to move the boat forward. The headsail, which is also known as a jib or genoa, is attached to the forestay and helps to control the boat’s direction by creating lift. Together, these two sails work together to provide speed and maneuverability.

A sloop is typically crewed by one or two sailors, although larger sloops may require more crew members to handle the sails and other equipment. The size of a sloop can vary greatly, from small dinghies used for recreational sailing to large ocean-going vessels used for racing or long-distance cruising.

Variations of Sloops

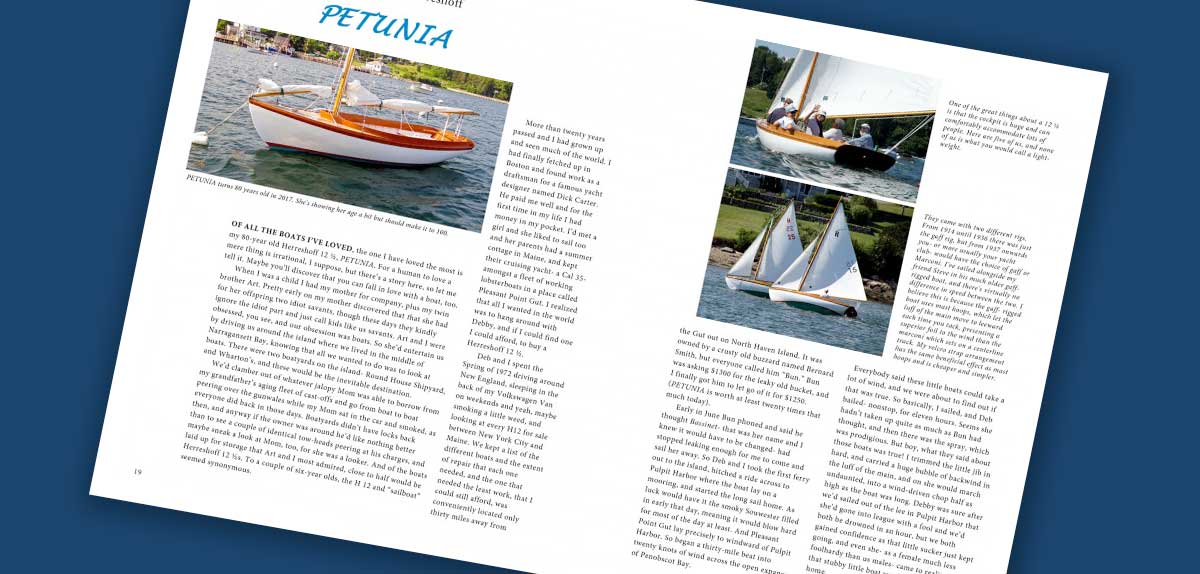

Bermuda-rigged sloop.

The Bermuda-rigged sloop is a classic design that has been around for centuries. It features a mainsail and a jib, which is a type of headsail. This design is popular among sailors because it is easy to handle and provides good performance in a wide range of wind conditions.

One of the advantages of the Bermuda rig is that it allows for more headsails to be used than other types of rigs, such as ketches or schooners. This means that sailors can adjust their sails to match changing wind conditions, giving them greater control over their sailing vessel.

Another advantage of the Bermuda rig is its simplicity. The sail plan is relatively easy to set up and maintain, making it an ideal choice for beginners or those who prefer a minimalist approach to sailing.

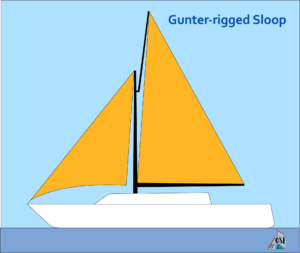

Gunter-Rigged Sloop

The Gunter-rigged sloop is another traditional design that has been around for centuries. It features a mainsail and a jib, but instead of using a masthead rig like the Bermuda sloop, it uses a gaff rigged mast with an additional spar called the gaff topsail.

This design was popular in the 19th century because it allowed sailors to carry more sail area without having to use taller masts. However, it fell out of favor in the early 20th century when newer designs were developed that provided better performance.

Despite this, there are still some sailors who prefer the Gunter rig because of its traditional look and feel. It can also be easier to handle than some other types of rigs because the sails are smaller and lighter.

Gaff-Rigged Sloop

The gaff-rigged sloop is similar to the Gunter rig in that it uses a gaff rigged mast with an additional spar called the gaff topsail. However, it also features a headsail like the Bermuda rig.

In the past, boats commonly used gaff rigged sails, but now they have mostly been replaced by Bermuda rig sails. These newer sails are simpler than the gaff rig and allow boats to sail closer to the wind.

Spritsail Sloop

The spritsail sloop is one of the simplest rigs available. It features a single sail called the spritsail, which is attached to a spar called the sprit. This design was popular among fishermen and other working boats because it was easy to set up and maintain.

Although not as popular as before, some sailors still prefer the simplicity of a spritsail rig. It’s a great option for those who want to focus on sailing without the added complexity of multiple lines or sail plans. This type of rig is also suitable for beginner sailors and those who want an easy-to-handle boat.

The Origin of the Word Sloop

The word “sloop” is believed to have originated from the Dutch word “sloep”, which means a small boat used for fishing or transportation. The Dutch were known for their seafaring skills and had a significant influence on maritime culture in Europe during the 17th century. As such, it’s no surprise that many nautical terms used today have Dutch origins.

In fact, the sloop was initially developed in Holland during the 16th century as a small, single-masted vessel used primarily for fishing and coastal trading. These boats were highly maneuverable and could navigate shallow waters with ease, making them ideal for use in Holland’s many canals and waterways.

As Dutch sailors began to explore further afield, they brought their sloops with them, using them as auxiliary vessels to transport goods and personnel between larger ships and shore. Over time, sloops evolved into larger vessels capable of longer voyages and more extensive cargo capacity.

History of Sloops

Sloops have been a popular type of ship for centuries, with their unique rigging and hull design allowing for greater speed and maneuverability compared to other vessels. Let’s take a closer look at the history of sloops and how they have evolved over time.

17th Century: The Birth of Sloops

Sloops first emerged in the 17th century as small, fast ships used for coastal trading and piracy. Their single mast and fore-and-aft sail plan allowed them to navigate shallow waters with ease, making them ideal for smuggling goods or evading authorities. Despite their reputation as pirate ships, sloops were also used by legitimate traders due to their speed and efficiency.

18th Century: Sloops in War

In the 18th century, sloops became increasingly popular among naval forces due to their speed and agility. The British Royal Navy used sloops as dispatch vessels and reconnaissance ships during times of war. Pirates and privateers also favored sloops due to their ability to outrun larger vessels. As a result, the term “sloop-of-war” was coined to describe a small warship with a single mast and crew of around 75 men.

19th Century: Racing Sloops

The 19th century saw the rise of yacht racing, with sloops becoming a popular choice among sailors due to their versatility and ease of handling. In fact, the first recorded yacht race took place in 1826 between two sloops on the Hudson River. Sloops continued to be used for racing throughout the century, with improvements in rigging and hull design leading to faster vessels.

Modern Times: Versatile Sloops

Today, sloops are still widely used for racing and cruising due to their versatility. They are often chosen by recreational sailors who want an easy-to-handle vessel that can navigate both shallow coastal waters and open seas. Modern sloops come in various sizes, from small day-sailers to larger cruising boats. Some sloops even incorporate multiple masts, such as the ketch rig , which features a smaller mizzen mast behind the main mast.

Advantages of a Sloop

Single mast: easier to handle and maneuver.

Sloops are popular sailboats that have a single mast, which makes them easier to handle and maneuver compared to other sailboat types. The simplicity of the sloop rig means that it requires less maintenance and is generally less expensive to maintain compared to other sailboat types. With only one mast, there are fewer lines and sails to manage, making it easier for sailors who are new to sailing or those who prefer a simpler setup.

The single mast design also allows for better visibility on the water since there is no obstruction from multiple masts or rigging. This feature is especially useful when sailing in crowded waters where you need to keep an eye out for other boats or obstacles.

Faster Sailing and Closer to the Wind

Another advantage of sloops is their speed. Sloops are generally faster than other sailboat types due to their streamlined design with fewer sails. The Bermuda sloop, for example, has a triangular mainsail and one or more headsails, allowing it to move quickly through the water with minimal drag.

Sloops can also sail closer to the wind than most other sailboats. This means they can tack (sail against the wind) more efficiently, allowing them to cover more ground in less time. The ability of a sloop’s sails to be adjusted easily helps in this regard as well.

Wide Variety Available

As the most popular contemporary boat, sloops are available in a wide variety. They come in different sizes and designs suitable for various purposes such as racing, cruising, or day sailing. Some sloops even have additional sails like mizzenmast or more headsails which make them more versatile.

For instance, some sloops have a mizzenmast located aft of the mainmast which provides additional support for larger boats during heavy winds. Other sloops may have multiple headsails that allow them greater flexibility when adjusting to different wind conditions. These additional sails can make a sloop more expensive to maintain, but they also provide greater versatility and options for the sailor.

Disadvantages of a Sloop

Limited sail options in heavy weather conditions.

Sloops are known for their simplicity and ease of handling, but they have some disadvantages that sailors should be aware of. One of the biggest drawbacks is the limited sail options in heavy weather conditions. Sloops typically have a single forestay that supports the mast, which means that they can only fly one headsail at a time. This can be problematic when sailing upwind in strong winds or heavy seas.

In these conditions, it’s often necessary to reduce sail area to maintain control and prevent damage to the boat or rigging. With a sloop, this usually means taking down the headsail and relying on the mainsail alone. While this can work well in moderate wind conditions, it may not provide enough power or stability in stronger winds.

Difficulty in Handling Larger Sails Alone

Another disadvantage of sloops is that they can be difficult to handle when sailing with larger sails alone. As mentioned earlier, sloops rely on a single forestay to support the mast and headsail. When you increase the size of the sail, you also increase the load on the forestay and rigging.

This means that you may need additional crew members to help manage larger sails safely. If you’re sailing solo or with a small crew, this can make it challenging to get the most out of your boat without putting yourself at risk.

Higher Loads on Mast and Rigging Due to Single Forestay Design

The single forestay design used by sloops also puts higher loads on both the mast and rigging compared to other sailboat designs. The forestay is responsible for supporting not only the headsail but also part of the mast itself.

This means that any stress placed on the headsail or rigging will be transferred directly to the mast through this single point of attachment. Over time, this can lead to fatigue and wear on both the mast and rigging components.

Increased Risk of Broaching in Strong Winds

Sloops are also more prone to broaching in strong winds compared to other sailboat designs. Broaching occurs when a boat is hit by a large wave or gust of wind from the side, causing it to heel over and potentially capsize.

Because sloops have a smaller cockpit and rely on a single forestay for support, they may be more susceptible to this type of event. This can be especially dangerous if you’re sailing in rough conditions or offshore where rescue may not be immediately available.

Reduced Stability Compared to Other Sailboat Designs

Another disadvantage of sloops is that they offer reduced stability compared to other sailboat designs. Sloops typically have a narrower beam and less ballast than other boats of similar size, which can make them feel less stable in heavy seas or choppy water.

This lack of stability can also affect your ability to maintain course and steer accurately, especially when sailing upwind or in challenging conditions. It’s important to understand the limitations of your boat and adjust your sailing style accordingly.

Conclusion: What is a Sloop?

With just one mast and a fore-and-aft rig, sloops are known for their simplicity and versatility. These characteristics make them an excellent choice for sailors of all levels. Whether you’re a seasoned sailor or just starting out, you’ll find that the design of a sloop allows for easy handling and maneuverability.

The single mast on a sloop is typically located towards the front of the boat. This placement provides several advantages when sailing upwind, the sail can be adjusted easily to maintain an optimal angle with respect to the wind. This is because there is only one sail to worry about, unlike other types of boats that may have multiple sails.

Similarly, when sailing downwind, a sloop’s sail can be adjusted quickly to take advantage of any changes in wind direction or speed. This flexibility makes it possible to navigate challenging weather conditions with ease.

External Links, See Also

For those looking for more technical information on sloops and other types of sailboats, the Boatdesign.net forum is an excellent resource. Here you can find discussions on everything from mast design to hull construction.

Finally, if you’re looking for some great books on sailing and sailboat design, be sure to check out “The Elements of Seamanship” by Roger C. Taylor or “Sailing Alone Around the World” by Joshua Slocum.

Similar Posts

Mainsail Furling Systems – Which one is right for you?

With the variety of options of mainsail furling systems available, including slab, in-boom, and in-mast systems, it can be challenging to determine which one best suits your needs. In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the pros and cons of each system, enabling you to make an informed decision that aligns with your sailing requirements….

What is a Ketch Sailboat?

Ketch boats are frequently seen in certain regions and offer various advantages in terms of handling. However, what is a ketch and how does it stand out? A ketch is a sailboat with two masts. The mainmast is shorter than the mast on a sloop, and the mizzenmast aft is shorter than the mainmast. Ketches…

Advantages of Catamaran Sailboat Charter

A catamaran sailboat charter is an exciting way to explore the beauty of the sea. Whether you are an experienced sailor or a first-timer, booking a catamaran sailboat charter has a lot of advantages that you can enjoy. In this article, we will discuss the advantages of booking a catamaran sailboat charter, so that you…

Whats the Difference between Standing Rigging and Running Rigging?

Running rigging refers to the movable lines and ropes used to control the position and shape of the sails on a sailboat. Standing rigging, on the other hand, refers to the fixed wires and cables that support the mast and keep it upright. As the sun rises on another day, we find ourselves immersed in…

Basic Sailing Terminology: Sailboat Parts Explained

Sailing is a timeless activity that has captivated the hearts of adventurous souls for centuries. But, let’s face it, for beginners, sailing can be as intimidating as trying to navigate through a dark, labyrinthine maze with a blindfold on. The vast array of sailing terminology, sailboat parts and jargon can seem like a foreign language…

How do Boats Float? Exploring the Science Behind Buoyancy

Sailboats float because the average density of the boat is less than the density of water. When boats displace as much water as it weights, this is known as the buoyancy force generated by Archimedes’ principle. If you’ve ever wondered how do boats float and therefor enable us to embark on thrilling water adventures, you’ve…

Sailboat Sloop: The Ultimate How To

Introduction:

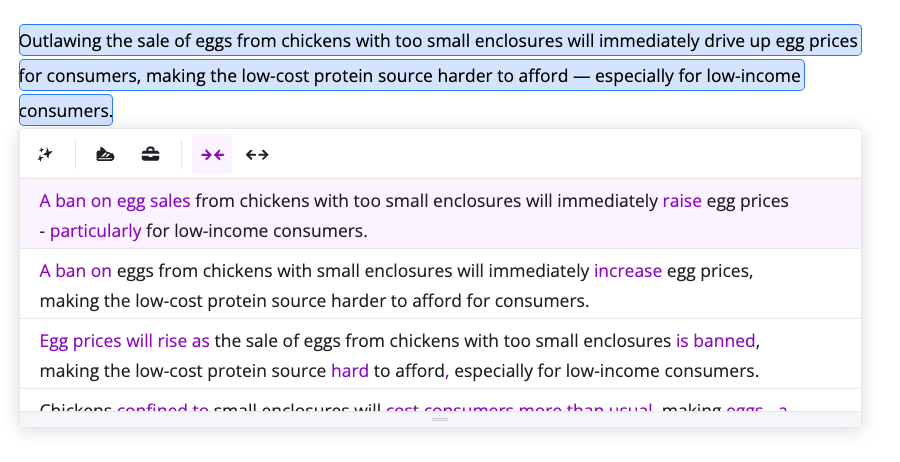

The sailboat sloop is a popular type of watercraft designed to cater to the needs of sailing enthusiasts and adventurers seeking thrilling journeys on the open water. These boats offer a balanced combination of performance, ease of handling, and comfortable accommodations. In this comprehensive comparison, we will delve into the key characteristics of sailboat sloops, including their design, features, rigging options, and discuss the top brands in the market.

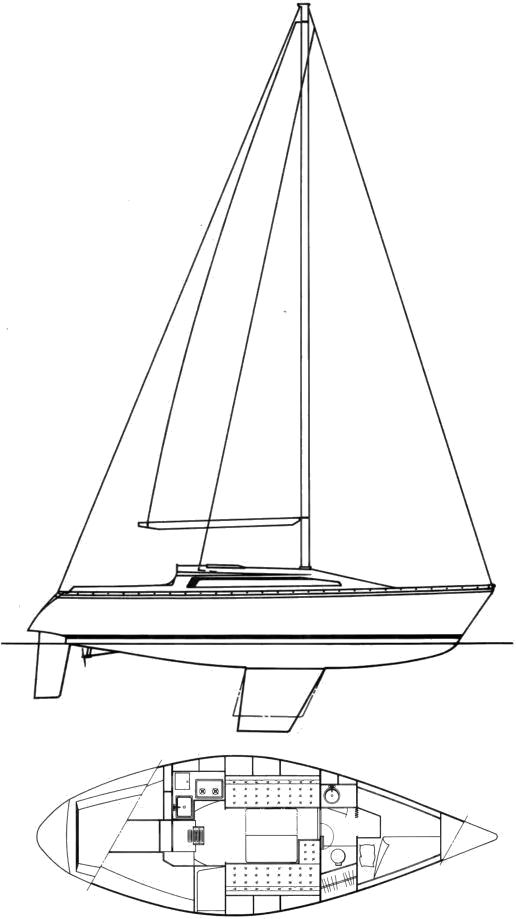

Sailboat Sloop Design and Purpose:

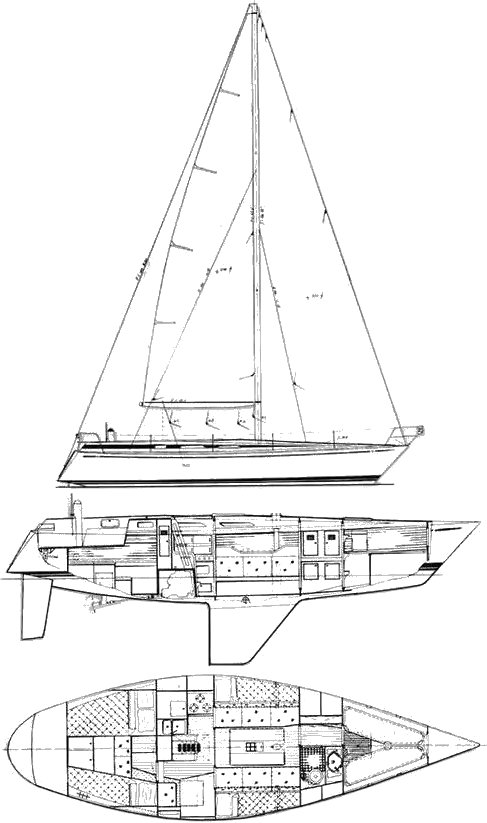

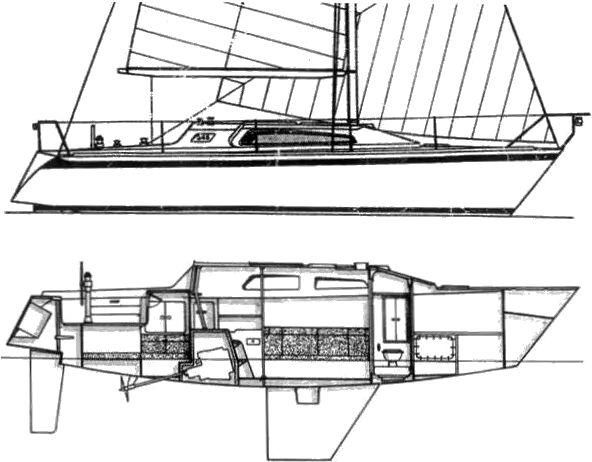

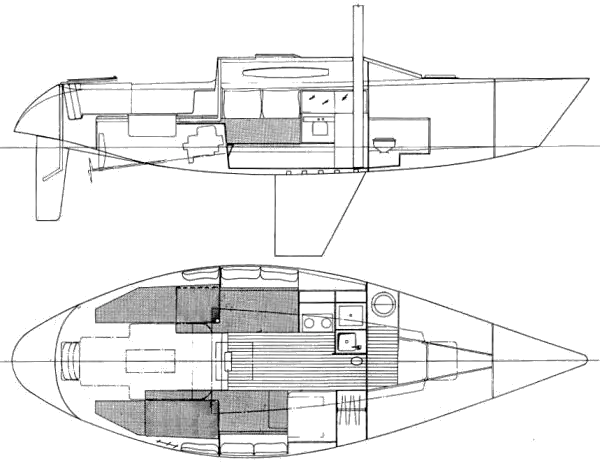

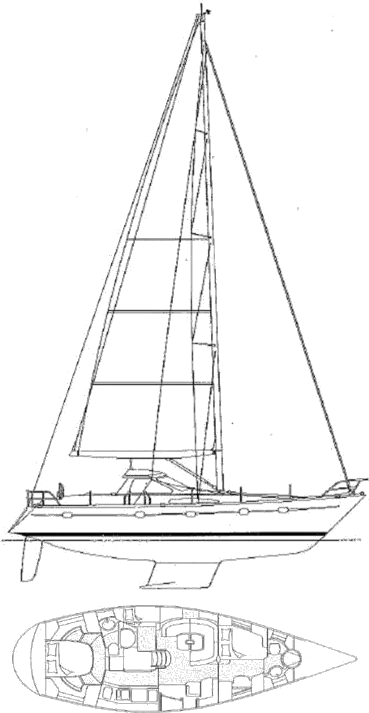

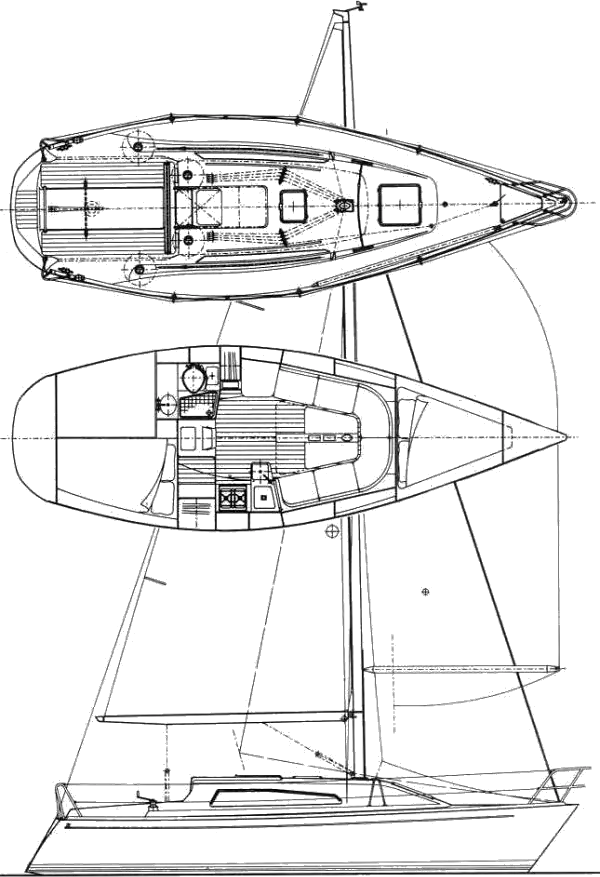

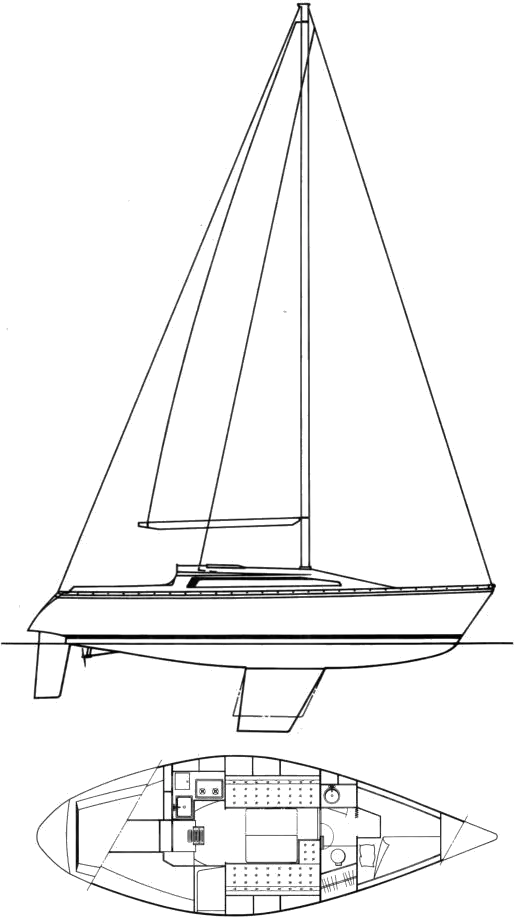

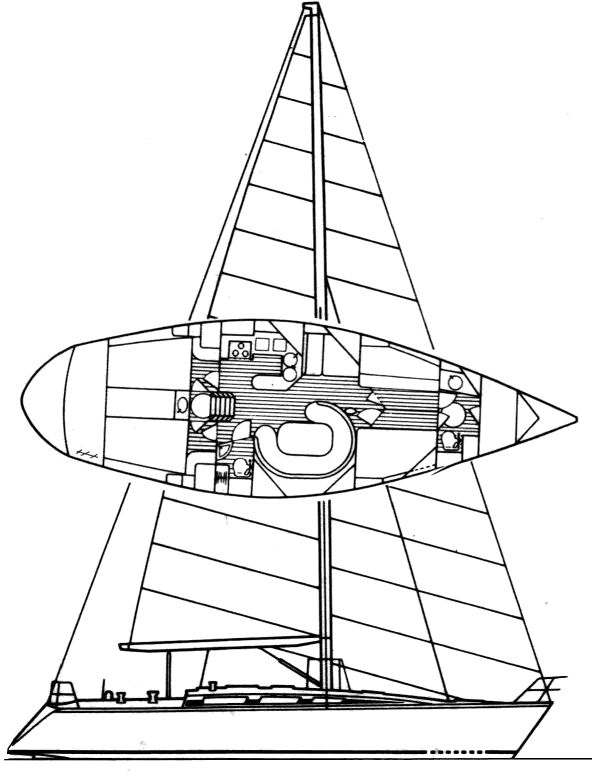

Sailboat sloops are meticulously designed to provide a versatile sailing experience. They typically feature a single mast and a sloop rig configuration consisting of a mainsail and a headsail, such as a genoa or jib. The hull design of sailboat sloops prioritizes stability, speed, and maneuverability, allowing sailors to navigate various sailing conditions with confidence. With their moderate displacement and keel or centerboard, sailboat sloops excel in coastal cruising as well as longer voyages.

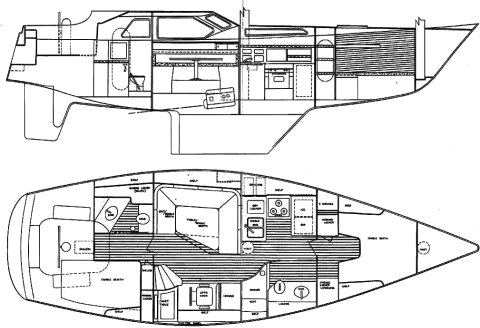

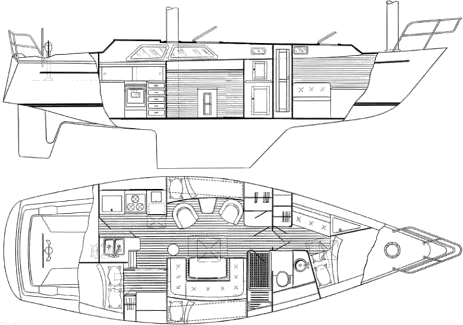

Sailboat Sloop Key Features:

Sailboat sloops have comfortable accommodations for extended stays on the water. It includes spacious cabins, a well-equipped galley, and a salon area for dining and relaxation. The interiors are designed to maximize living space and provide essential amenities for a comfortable sailing experience.

- Efficient Sail Handling Systems: Sailboat sloops feature efficient sail-handling systems that make it easy to adjust sails for optimal performance. These systems often include roller furling headsails and in-mast or in-boom furling mainsails, allowing sailors to quickly and effortlessly adapt to changing wind conditions. The incorporation of winches and control lines further enhances the ease of sail handling.

- Stability and Performance: Sailboat sloops prioritize stability and performance to deliver an exhilarating sailing experience. Their hull designs and keel configurations provide stability and reduce excessive rolling in rough seas. Sailboat sloops are known for their balanced performance, combining speed and maneuverability without compromising on comfort, allowing sailors to enjoy both leisurely cruising and spirited sailing.

The Sloop Rig:

The sloop rig consists of a single mast and two sails—a mainsail and a headsail (genoa or jib). This rig allows for easy handling and adaptability in various wind conditions, making it suitable for a wide range of sailing styles, from leisurely coastal cruising to more challenging offshore passages.

Appropriate Buyers and Considerations:

Sailboat sloops are ideal for sailing enthusiasts who appreciate a balanced combination of performance and comfort. When considering a sailboat sloop, potential buyers should take the following factors into account:

- Sailing Preferences: Determine your preferred style of sailing, whether it’s coastal cruising, day sailing, or longer voyages. This will help you choose a sailboat sloop that aligns with your intended use and sailing goals.

- Accommodation Needs: Consider the number of people you plan to accommodate on board and ensure the boat provides sufficient sleeping quarters and living space. Evaluate the functional galley, marine head, and storage capacity.

- Budget: Sailboat sloops vary in price depending on factors such as size, brand, features, and rigging options. Establishing a budget and researching different models within your price range will help you find the best sailboat sloop.

Sailboat Sloop Top Brands:

When searching for a sailboat sloop, it’s essential to explore reputable brands known for their quality construction, sailing performance, and cruising-specific features. Here are three top sailboat sloop brands worth considering:

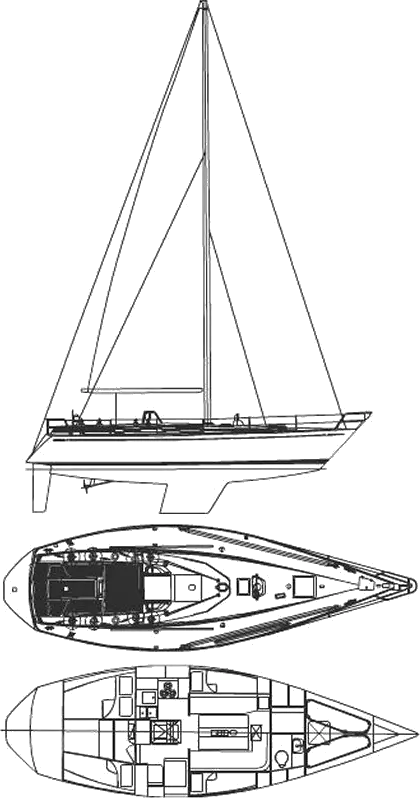

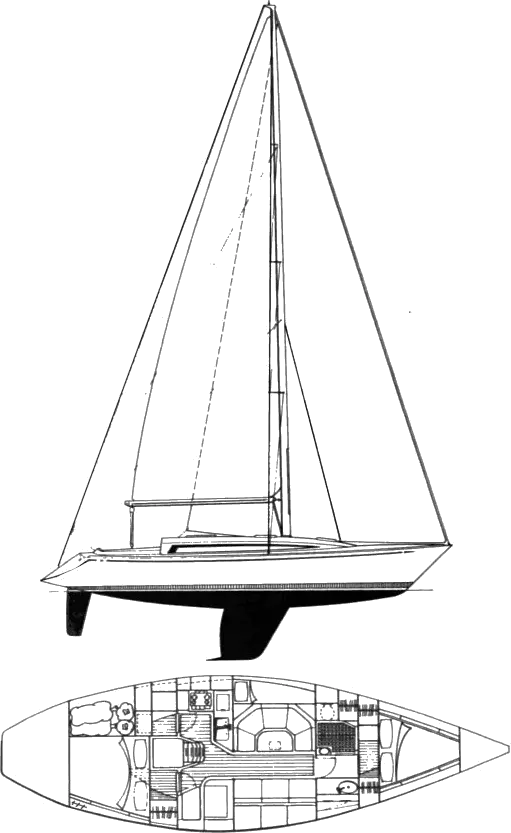

- Beneteau is a renowned sailboat sloop brand that has earned a stellar reputation for its extensive range of sailboats designed for cruising and racing. Known for their exceptional performance, innovative design, and superior craftsmanship, Beneteau sailboats are favored by sailors worldwide.

- Beneteau sailboats are meticulously engineered to deliver optimal sailing performance. Their sloop designs incorporate advanced hull shapes, efficient sail plans, and cutting-edge rigging systems, allowing for excellent speed and maneuverability on the water. Whether you’re navigating coastal waters or embarking on offshore adventures, Beneteau sailboats offer a perfect balance of performance and comfort.

- The interiors of Beneteau sailboats are carefully designed to maximize space and functionality. With a focus on ergonomic layouts and high-quality materials, these sailboats provide comfortable accommodations for extended stays. Beneteau offers a variety of cabin configurations, ensuring that sailors have ample room for sleeping, dining, and relaxing onboard.

- Beneteau sailboats cater to a diverse range of sailing preferences and needs. From compact cruisers to luxurious yachts, the brand offers models suited for different cruising styles and requirements. Whether you’re a seasoned sailor or a novice looking to embark on your first sailing adventure, Beneteau sailboats provide the performance, comfort, and versatility to meet your expectations.

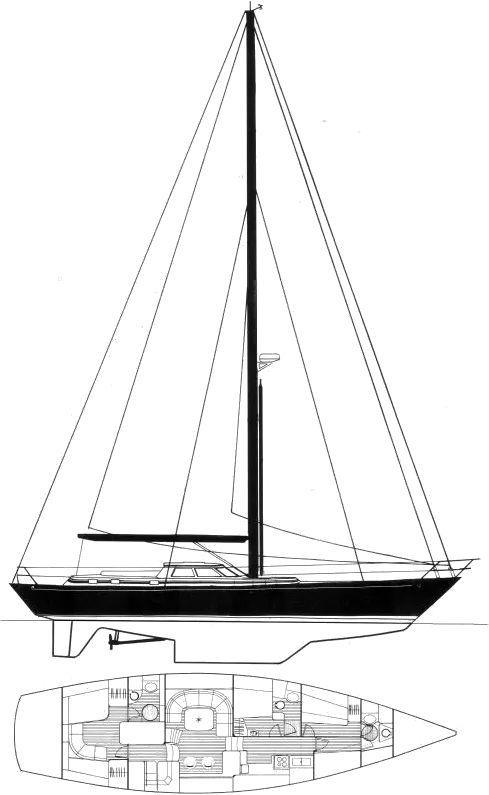

- Jeanneau is a prestigious sailboat sloop brand that has become synonymous with elegance, performance, and cruising comfort. With a strong emphasis on innovative design, quality construction, and attention to detail, Jeanneau sailboats are highly regarded by sailing enthusiasts around the globe.

- Jeanneau sailboats are designed to deliver exceptional sailing performance. Their sloop configurations feature sleek hulls, efficient sail plans, and advanced rigging systems, enabling sailors to enjoy exhilarating experiences on the water. These sailboats are known for their stability, responsiveness, and ease of handling, making them ideal for both short trips and long-distance cruising.

- The interiors of Jeanneau sailboats exude sophistication and comfort. Crafted with meticulous care, the cabins offer spacious living areas, ergonomic layouts, and high-quality finishes. Jeanneau prioritizes creating inviting and functional spaces, ensuring that sailors have a cozy retreat to relax and unwind after a day of sailing.

- Jeanneau sailboats encompass a wide range of models, accommodating different sailing preferences and needs. From compact cruisers to luxurious yachts, the brand offers options for sailors of all levels of experience. With their focus on performance, comfort, and stylish design, Jeanneau sailboats continue to impress and inspire sailors worldwide.

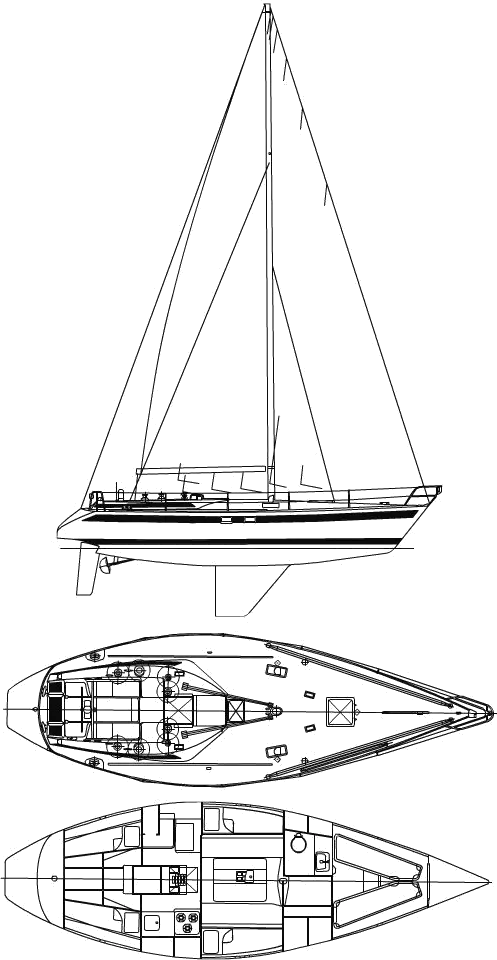

Hylas Yachts:

- Hylas Yachts is a renowned sailboat sloop brand known for its exceptional craftsmanship, luxurious interiors, and outstanding sailing performance. They are meticulously built with attention to detail, incorporating high-quality materials and innovative design elements.

- Sailors appreciate Hylas Yachts for their seaworthiness and excellent performance under sail. These sailboat sloops feature advanced rigging systems, efficient sail handling, and well-balanced hull designs. Hylas Yachts are designed to offer a perfect balance of speed, stability, and comfort, making them a preferred choice for long-distance cruising and offshore passages.

- The interiors of Hylas Yachts are crafted with elegance and functionality in mind. The cabins are spacious, featuring luxurious accommodations and ample storage space. Hylas Yachts are known for their attention to detail in the craftsmanship of their interiors, providing a comfortable and inviting environment for extended stays on board.

- Hylas Yachts offer a range of models to cater to different sailing preferences and requirements. Whether you’re seeking a compact sloop for coastal cruising or a larger yacht for extended offshore adventures, Hylas Yachts provides options to suit various needs. Their commitment to quality, performance, and luxury has solidified Hylas Yachts as one of the top brands in the market.

Conclusion:

Sailboat sloops provide sailing enthusiasts with a versatile and thrilling experience, combining performance, ease of handling, and comfortable accommodations. When considering a sailboat sloop, it’s important to evaluate the design, key features, rigging options, and accommodation needs to find a boat that suits your specific sailing requirements. Exploring reputable brands such as Beneteau, Jeanneau, and Hanse will assist you in making an informed decision and selecting a sailboat sloop that delivers both performance and comfort on the water.

We encourage you to use Rabbet to connect with the rest of the boating community! Hop onto our Learn tab to find more articles like this. Join our various forums to discuss with boating enthusiasts like you. Create an account to get started.

Visit us on Pinterest to collect content and inspire others.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related Articles

Liveaboard! The Ultimate How To

Become a liveaboard! Swap your landlubber life for a life on the high seas? Here’s everything you need to know to become a full-time boat-dweller!

Sailboat Cutters: The Ultimate Guide

Discover the best sailboat cutter for an extraordinary sailing adventure. Explore top brands like Hallberg-Rassy, Swan & Island Packet in our ultimate guide.

Catamaran Sailboats: The Ultimate Guide

Catamaran sailboats offer exceptional stability, comfort, and living space for sailing enthusiasts. Learn about their design, key features, and top brands.

Sailboat Cruisers: The Ultimate How To

Introduction: Sailboat cruisers are specially designed watercraft built to cater to the needs of sailing enthusiasts and those seeking adventurous journeys on the open water.…

Ketch Sailboats: The Ultimate Guide

Discover the allure of ketch sailboats – versatile sail plans, comfortable accommodations, and reliable performance. Learn more about ketch sailboats here.

Leave a Reply

[…] Sloop Rig: The sloop rig is the most common rigging configuration for catamarans. It features a single mast with a mainsail and a headsail, usually a genoa or jib. This rig provides versatility and ease of handling, making it suitable for a wide range of wind conditions. […]

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- See blocked member's posts

- Mention this member in posts

- Invite this member to groups

- Message this member

- Add this member as a connection

Please note: This action will also remove this member from your connections and send a report to the site admin. Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

Discover more from Rabbet

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Jordan Yacht Brokerage

We Never Underestimate Your Dreams

Sailboat rig types: sloop, cutter, ketch, yawl, schooner, cat.

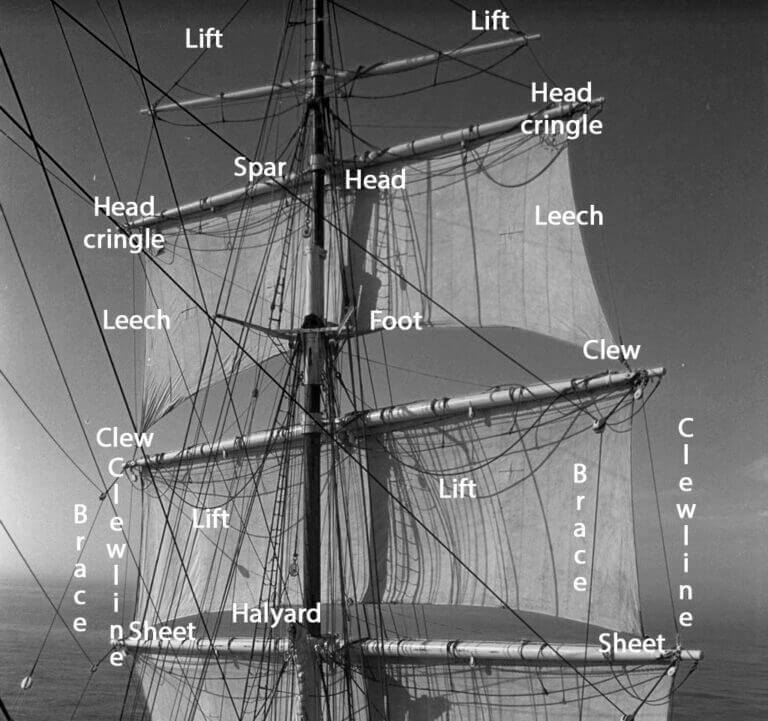

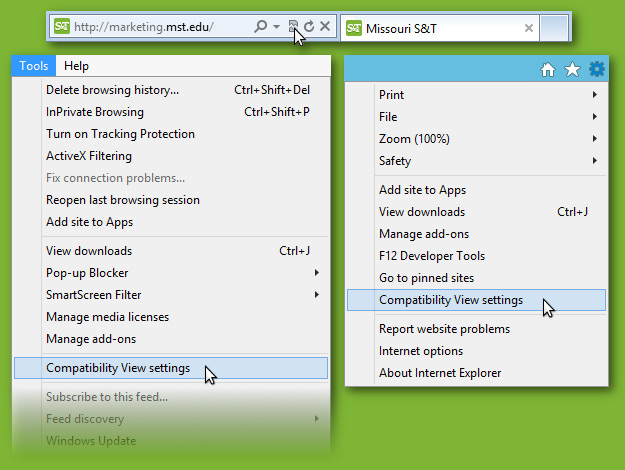

Naval architects designate sailboat rig types by number and location of masts. The six designations are sloop, cutter, cat, ketch, yawl, and schooner. Although in defining and describing these six rigs I may use terminology associated with the sail plan, the rig type has nothing to do with the number of sails, their arrangement or location. Such terms that have no bearing on the rig type include headsail names such as jib, genoa, yankee; furling systems such as in-mast or in-boom; and sail parts such as foot, clew, tack, leach, and roach. Rig questions are one of the primary areas of interest among newcomers to sailing and studying the benefits of each type is a good way to learn about sailing. I will deal with the rigs from most popular to least.

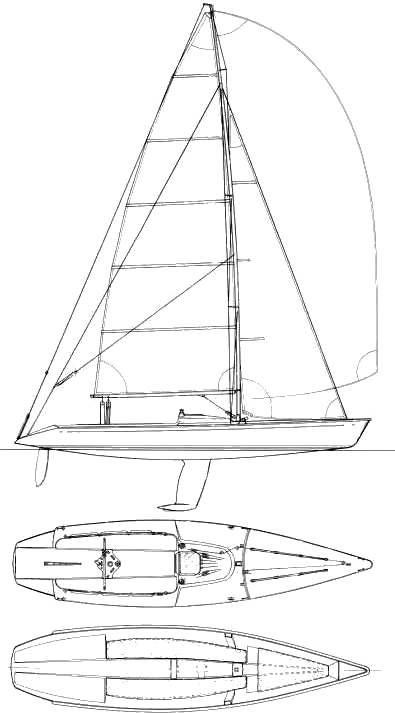

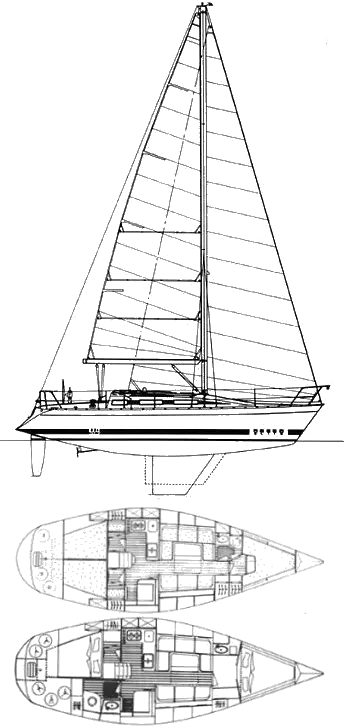

Sloop The simplest and most popular rig today is the sloop. A sloop is defined as a yacht whose mast is somewhere between stations 3 and 4 in the 10 station model of a yacht. This definition places the mast with two thirds of the vessel aft and one third forward. The sloop is dominant on small and medium sized yachts and with the shift from large foretriangles (J-dimension in design parlance) to larger mains a solid majority on larger yachts as well. Simple sloop rigs with a single headsail point the highest because of the tighter maximum sheeting angle and therefore have the best windward performance of the rig types. They are the choice for one-design racing fleets and America’s cup challenges. The forestay can attached either at the masthead or some fraction below. These two types of sloops are described respectively as masthead or fractionally rigged. Fractionally rigged sloops where the forestay attaches below the top of the mast allow racers to easily control head and main sail shapes by tightening up the backstay and bending the mast.

Cutter A cutter has one mast like the sloop, and people rightfully confuse the two. A cutter is defined as a yachts whose mast is aft of station 4. Ascertaining whether the mast is aft or forward of station 4 (what if it is at station 4?) is difficult unless you have the design specifications. And even a mast located forward of station 4 with a long bowsprit may be more reasonably referred to as a cutter. The true different is the size of the foretriangle. As such while it might annoy Bob Perry and Jeff_h, most people just give up and call sloops with jibstays cutters. This arrangement is best for reaching or when heavy weather dictates a reefed main. In moderate or light air sailing, forget the inner staysail; it will just backwind the jib and reduce your pointing height.

Ketch The ketch rig is our first that has two masts. The main is usually stepped in location of a sloop rig, and some manufactures have used the same deck mold for both rig types. The mizzen, as the slightly shorter and further aft spar is called, makes the resulting sail plan incredibly flexible. A ketch rig comes into her own on reaching or downwind courses. In heavy weather owners love to sail under jib and jigger (jib and mizzen). Upwind the ketch suffers from backwinding of the mizzen by the main. You can add additional headsails to make a cutter-ketch.

Yawl The yawl is similar to the ketch rig and has the same trade-offs with respect to upwind and downwind performance. She features two masts just like on a ketch with the mizzen having less air draft and being further aft. In contrast and much like with the sloop vs. cutter definition, the yawl mizzen’s has much smaller sail plan. During the CCA era, naval architects defined yawl as having the mast forward or aft of the rudderpost, but in today’s world of hull shapes (much like with the sloop/cutter) that definition does not work. The true different is the height of the mizzen in proportion to the main mast. The yawl arrangement is a lovely, classic look that is rarely if ever seen on modern production yachts.

Schooner The schooner while totally unpractical has a romantic charm. Such a yacht features two masts of which the foremost is shorter than the mizzen (opposite of a ketch rig). This change has wide affects on performance and sail plan flexibility. The two masts provide a base to fly unusual canvas such as a mule (a triangular sail which spans between the two spars filling the space aft of the foremast’s mainsail). The helm is tricky to balance because apparent wind difference between the sails, and there is considerable backwinding upwind. Downwind you can put up quite a bit of canvas and build up speed.

Cat The cat rig is a single spar design like the sloop and cutter, but the mast location is definately forward of station 3 and maybe even station. You see this rig on small racing dinghies, lasers and the like. It is the simplest of rigs with no headsails and sometimes without even a boom but has little versatility. Freedom and Nonesuch yachts are famous for this rig type. A cat ketch variation with a mizzen mast is an underused rig which provides the sailplan flexibility a single masted cat boat lacks. These are great fun to sail.

Conclusion Sloop, cutter, ketch, yawl, schooner, and cat are the six rig types seen on yachts. The former three are widely more common than the latter three. Each one has unique strengths and weaknesses. The sloop is the best performing upwind while the cat is the simplest form. Getting to know the look and feel of these rig types will help you determine kind of sailing you enjoy most.

5 Replies to “Sailboat Rig Types: Sloop, Cutter, Ketch, Yawl, Schooner, Cat”

Thanks for this information. I’m doing my research on what type of sailboat I will eventually buy and was confused as to all the different configurations! This helped quite a bit.

- Pingback: ketch or schooner - Page 2 - SailNet Community

- Pingback: US Coast Guard Auxiliary Courses – Always Ready! | Escape Artist Chronicles

Being from the south, my distinction between a ketch and a yawl: if that mizzen falls over on a ketch, the boat will catch it; if it falls over on a yawl, it’s bye bye y’all.

I thought a Yawl had to have the mizzen mast behind the rudder and a ketch had the mizzen forward of the rudder.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Great choice! Your favorites are temporarily saved for this session. Sign in to save them permanently, access them on any device, and receive relevant alerts.

- Sailboat Guide

Ron Holland

My first design, the 26 ft. sloop ‘White Rabbit’ was created in 1966 during the 3 year period I attended my boat building apprenticeship in Auckland, New Zealand. Six years later, while working in the engineering department of production yacht builder, Morgan Yachts in St. Petersburg, Florida, I designed a 24 ft. racer, ‘Eygthene’, to the IOR Quarter Ton Rule. This yacht won the 1973 Quarter Ton Championships in Torbay, England, and enabled me to secure the design commission for ‘Golden Apple’ from Irish yachtsman, the late Hugh Coveney. The success of this yacht was the foundation of my Irish based yacht design business. These small racing yachts formed the backbone of the Ron Holland organisation for several years, with a string of successes in level rating world championships and Admiral’s Cup events. Racing at the highest level of international competition. Based on the racing success of the Admiral’s Cup yachts came commissions for maxi racers, the largest yachts competing internationally. In 1980, ‘Kialoa’ and ‘Condor’ established the Ron Holland design philosophy in this area of the business and lead to commissions for larger, performance oriented cruising yachts. ‘Whirlwind XII”, my first design over 100 ft. in length, was launched from the Royal Huisman Shipyard in 1986 and paved the way for a wide variety of design commissions from clients who demanded beautiful, safe, comfortable cruising yachts, capable of worldwide voyaging. The common denominator is these were all performance oriented cruising yachts, the benchmark of the Ron Holland Design philosophy still in force with today’s design commissions. 1999 has seen important new projects that included my first interior design commission, as well as my first motor yacht design work. New areas of activity that I have found stimulating and a logical extension of a lifetime’s work in the marine design field. Reviewing the presented Ron Holland designs will show the variety of design approaches that have been taken, specifically to ensure my clients achieve a yacht that fulfils their personal requirements. My organisation prides itself with interpreting the client’s goals and integrating these with aesthetically correct and performance oriented design solutions.

55 Sailboats designed by Ron Holland

Jeanneau Rush 31

Parker 21 (Trailer Sailer 21)

Nicholson 33 3/4 Ton

Discovery 55

Nicholson 303

Nicholson 1/2 Ton

Swan 43 (Holland)

Nicholson 345

Golden Shamrock 30

Westerly ocean 43.

Trintella 47

Manzanita (Holland)

Bombardier 7.6

Freedom 39 Pilot House

Eygthene 24

Feeling 546

Jeanneau Rush Royale 31

Polaris 37 (holland), discovery 58.

Polaris 33 (Holland)

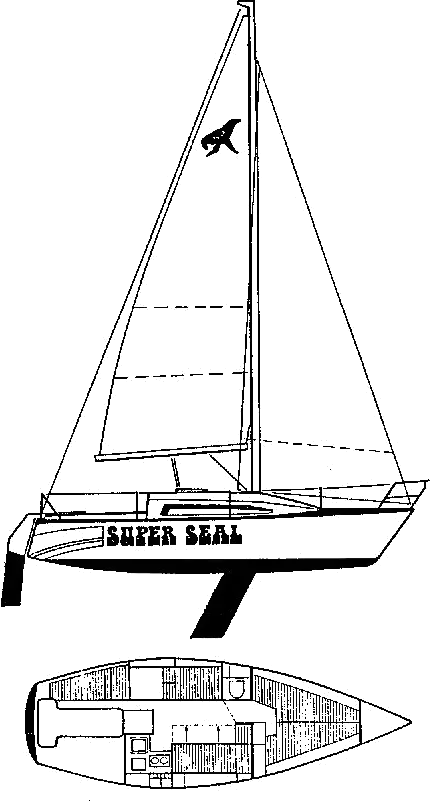

Super Seal 26

Belliure 2.5

Belliure 63

Feeling 1350

- About Sailboat Guide

©2024 Sea Time Tech, LLC

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Find anything, super fast.

- Destinations

- Documentaries

Fresh from the boards of Tony Castro Yacht Design, this 62 metre sloop yacht concept is the largest sub-500GT sailing yacht design possible, according to the studio.

Measuring 62.5 metres from bow to stern with a 12.3 metre beam and 6.5 metre draft, this future-proof concept is bursting with revolutionary technologies. Key on board features include power generators capable of operating while the yacht is underway and cobalt-free batteries. Generated energy can be used to power hotel loads both silently and emissions-free.

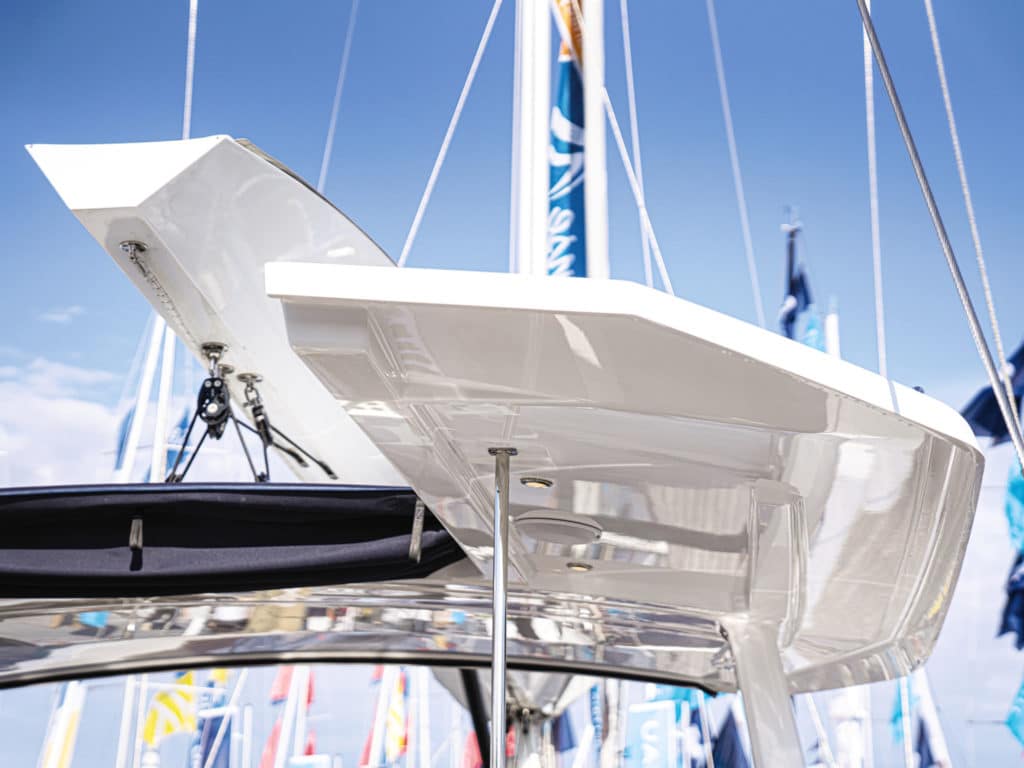

Elsewhere, the glazed saloon roof is made from insulating and thermal glass that can block out the sunlight at the touch of a button. The design also features glass bulwarks, a first-time sailing yacht feature, according to the studio. This provides guests relaxing in the cockpit with clear views of the ocean below as they glide through the water under sail.

This 62 metre sailing superyacht is intended as a performance-cruiser with particular attention paid to the amenities needed when at anchor. The main deck saloon extends into a spacious open air aft deck with ample relaxation spots and easy access to the sea. The circular "skydeck" helm station meanwhile is a standout feature that provides excellent visibility of the yacht under sail.

Inside, the yacht features a minimalistic interior with an open plan layout and abundance of natural light thanks to the overhead glass coachroof and large windows on the lower decks. Scandinavian-inspired, the interior features soft, high quality fabric and leather combinations paired with light brushed oak furniture for an understated elegance and atmosphere of pure luxury.

Elsewhere, the yacht's design boasts high performance under sail thanks to cutting edge naval architecture. The hull shape and appendages are optimised with the help of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) executed by D3 Technologies, working in partnership with VPP simulations to create the perfect balance of innovative design and superior performance. The result is an elegant, timeless design, beautiful to the eye with balanced proportions and performance to match.

Creative Team

- Exterior Designer Tony Castro Yacht Design View profile

- Interior Designer Tony Castro Yacht Design View profile

- Ordered by Shipyards & Yacht Brands

- Ordered by Date

- Yacht Designers

- About and Contact

- Yacht Support Vessels

- Tenders & Toys

- Some interesting other sites in the superyacht world

NGONI // Royal Huisman // Dubois

Royal huisman presents the 58m high-performance sloop ngoni that wears correctly the byname "the beast" - penned by the late ed dubois..

Photos were taken by Breed Media

Ngoni is one of the most innovative designs that come to real life. I like those owners who bring courage into the superyacht industry to realize those progressive projects. The owner is a highly experienced yachtsman and offshore racing sailor. The design brief said that the owner wanted a luxurious cruising go-anywhere yacht with high-performance DNA. I haven’t been on board, but I think the project stakeholders delivered precisely that. The statement of requirements in a nutshell:

“Build me a beast. Don’t build me a wolf in sheep’s clothing. This has to be an edgy and innovative weapon; fast and furious.”

Owner of the yacht

Royal Huisman’s subsidiary company RONDAL built the impressive 71m carbon-fiber mast with components by Carbo-Link . Even the style-to-order performance furling boom with a length of 24m could be a big boat by itself and reflects Ngoni ‘s profile design.

The haute couture is most excellent 3 Di canvas , tailored by North Sails The yacht wears a total sail area of 1,950 sqm (upwind) and 3,093 sqm (downwind).

The garderobe contains:

Ed Dubois (1952 – 2016) said:

“The bigger the model, the more accurate the results, because you can scale everything except the viscosity of water. Our aim is to reduce the wetted surface to minimize drag, while still retaining good stability. The hull lines will be finalized by November following the results of the tank tests.”

A Williams 565 jet tender is stored forward under the flush deck. A hidden crane moves the dinghy in or out of the water. The foredeck also contains a pool and enough space set up a sunbathing area with sunshade. Guests can enter the tender via the beach deck with the fold-out swimming platform and an inviting staircase to the cockpit.

Interior of Ngoni

NGONI ‘s Interior design is a creation by Rick Baker and Paul Morgan with signature furniture pieces by Francis Sultana . The full-beam owners’ suite at the aft features direct access to the beach deck, a gym, and a study that transforms into further guest areas alongside the two permanent cabins.

“Accent pieces and exotic finishes will be created in the workshop of London-based Rick Baker Ltd. Having been involved in some of the most high-profile projects on the planet, The Light Corporation has been asked to artfully shed light on the project.”

The deckhouse has two distinct areas. The front part is dedicated to the crew with navigation desk and direct access down to the crew area with the mess, galley, and six double crew cabins. The rear part is a socializing area with coffee table seating, dining, and a bar.

Comments on the project

“Given their reputation for excellence, Royal Huisman was the owner’s choice of shipyard from the very start. This is a thought-provoking design that does not take for granted the marriage of high performance, style, and comfort. She’s a design that marks a fresh and progressive turning point in our long and successful history. This is some yacht, inspired by a client looking for the next new, new thing; a dream project for both designer and shipyard.”

Alice Huisman:

“A great client, a great design team, and a great project. Everything about this project has our name on it: Royal Huisman is the perfect fit for every aspect of the project and the requirements to build it.”

Main Specifications of NGONI

Length Overall

Draft (Keel Up)

Draft (Keel Down)

Profile & General Arrangement

Deck Layout

General Arrangement

Last but not least: Interviews with the naval architect and interior designer of Ngoni

Naval architect ed dubois.

ED: The owner wanted me to take a fresh look at large yacht design. He wanted me to go back to my roots in the late 1970s and ‘80s when we were designing race boats, but he also knew we had designed a number of high-performance yachts that were nevertheless seaworthy and comfortable cruisers. So I had to reset my internal computer, if you like, and look hard at how we could save weight and add strength. That’s how the reverse sheer came about.

Can you explain the concept behind the reverse sheer?

ED: Think of a sloop as a bow and arrow: the bow is the hull, the arrow is the mast and the string is the forestay and backstay. You can imagine that tension creates an awful lot of bending moment, which is fine if you can compensate with a strong, deep beam in the structural sense, but the Beast has a relatively low freeboard and shallow beam with no structural superstructure. Then you make the situation worse by making holes in the deck for tender bays, sail lockers, and hatches – metal that would usually resist the compression in the deck. You can overcome that by adding a substantial sheer strake and Ngoni has a top plate of solid 35mm aluminum that acts like a ring beam around the hull, but it’s still a struggle to come up with the required stiffness. So then I started thinking about a reverse sheer, which is much like the structure of a bridge where the road is convex to resist the compression created by the weight of the traffic. We ran it through our structural analysis program and suddenly we had a 12 percent increase in stiffness for the same weight. It’s something you sometimes see on high-performance boats like Samurai, but this is the first time I’ve designed a sailing yacht with a reverse sheer.

It also affects the exterior profile, of course. Was the owner happy with the look of the boat?

ED: He wanted a yacht that was fast and punchy without losing the concept of a world cruising boat, which allowed me to think outside the box and defy convention. I remember when he initially came to the office I sketched out a design and he said, “It’s OK, but a bit ordinary. What are you going to do now?” I went away and came up with the reverse sheer, but was worried he might not like it. The next time we met in London I showed him the design and he loved it – in fact, he gave me a big bear hug! Actually, Ngoni has a convex sheer at the maximum bending moment amidships that transforms into a concave sheer aft, which looks more attractive and provides better visibility from the cockpit.

To what extent were you involved in the interior layout and design?

ED: With all our designs – except Twizzle, because we joined the project later – we’ve developed the initial space planning. As naval architects, we know where the primary elements such as the mast, the keel box, and the engine room should be. The associated structures around these have a profound effect on the interior layout, especially on a sailing boat. I also very much enjoy dealing with the architecture – as opposed to the naval architecture – of a boat: the flow from one space to another and the lifestyle the owner enjoys (or endures!) on board. So we created the general arrangement and introduced some of the curved shapes into the interior, which provided the template for the interior designers Rick Baker and Paul Morgan.

There is a fine distinction between speed and comfort; does that mean compromises had to be made?

ED: I prefer the word “balance” to “compromise”. To produce a balanced design you have to understand the true purpose of the boat from the owner’s perspective. That means you have to get to know him or her well enough to understand what they really want, which is not always easy as some owners have very clear ideas and others are not too sure. The owner of Ngoni is an experienced sailor who has raced in the Fastnet and Sydney-Hobart, and he knew I understood both the racing and cruising side. Like Frers and Briand, I started my career designing race boats and then transferred into large cruising yachts, so my job as a designer today is to get the right balance of speed, seaworthiness and long-range cruising ability based on the owner’s brief. I don’t think you can do that successfully unless you’ve sat for hours on the weather rail of a boat you’ve designed yourself and got cold and wet and possibly frightened or felt the excitement when you win and disappointment when you lose. You learn how a sailing boat behaves in all conditions on the race course – it is that experience that has given me the confidence to design a large sailing yacht and be pretty certain it’s going to work.

Given the need for speed, was a carbon fiber hull ever considered?

ED: It was, briefly, at the very beginning. The owner wanted to know about all the options and we presented him with comparisons in terms of weight, cost and build times. But there were other considerations at stake: sure, we could make a lighter and faster boat out of carbon, but would it be as comfortable and suitable for world cruising? Carbon hulls have a more aggressive motion at sea, which beyond the issue of seasickness is not very comfortable for long-range cruising. They also tend to be noisy, so some of the weight you’ve saved goes back on the boat as acoustic insulation. Again, it all came down to balance: understanding the true purpose of the yacht and coming up with the right formula, which is the delicious thing about being a designer. It’s like the satisfaction you get from solving a complicated mathematical equation. And people put their trust in you and pay you do it!

Interior Designer Rick Baker Ltd.

Please introduce yourselves

Rick Baker Limited is a bespoke cabinetmaking company which is very firmly art based. Both myself (Rick Baker) and co-director, Paul Morgan, have been through the art college system – I studied illustration and fine art, and Paul originally started off studying architecture before transferring to furniture design and manufacture.

In my twenties, I moved into furniture design and it did not take too long before we became involved with clients that were looking for originality of design and exemplary workmanship. As the company has grown, so has our reputation for producing quirky one-offs.

We employ twelve cabinetmakers and are fortunate to have never needed to advertise for work.

What brief were you given?

We have worked on many projects for these clients, and they asked if we could come up with a scheme for the interiors for the yacht. We were obviously delighted to be involved and had a series of meetings to determine the brief and direction for the yacht styling.

What was your initial reaction?

The design of the yacht is so unique, and it is obviously very exciting to be part of the team working on such a ‘one-off’. The curved shape of a yacht calls for a different approach – we have made a lot of curved furniture, but it was always to fit into square rooms!

Did the brief present any opportunities?

Yes, it was fantastic to meet the team involved in the building of the yacht. It has given us great insight at the highest level. It has also been very interesting to see how the boatyard approaches manufacture generally.

This project also presents us with an incredible opportunity to bring some new ideas to the more traditional styling of many current yachts.

Are there challenges to overcome?

The main challenge comes from the fact that, although we have designed and made freestanding pieces for motor yachts in the past, we have never been asked to design the complete interior of a sailing yacht.

But this also means we can challenge the status quo. We design with only half an eye on what supposedly can or can’t be done on a yacht, then, with the advice of Royal Huisman, we resolved most problems together.

What are the steps between brief and delivery?

We have a relatively simple design process which starts with a client meeting where we throw lots of ideas into the air – we land some of those ideas and we write copious notes. We then work on visuals and scale drawings to present to the clients and then rework those drawings with the design development that has come out of that meeting. We have been fortunate to work closely on several projects for these clients and have developed an understanding of their ideas, likes and dislikes.

How do you collaborate with the project team?

We had initial design concept meetings with Ed Dubois and Royal Huisman to agree to a strategy. And, as I have already mentioned, we work with Royal Huisman to make sure our concepts are fit for purpose as part of a superyacht interior. Also, the experience and advice from Goddy (Project Manager) and Iain Cook (Build Captain) have been invaluable.

Is there an overall ‘theme’?

The yacht is a total one-off, with a unique design by Ed Dubois, and the interiors had to reflect the same state of the art design. So we have consciously avoided giving the yacht a theme but rather chose to make the different areas very individual. It was important to us to not let the craft feel like a hotel and to avoid repetition in the cabins etc.

Are you using any unusual materials?

Innovative design still has to be practical and visually comfortable. The ‘standard’ response would be to mix high-sheen lacquer and hardwoods. Instead, we have selected some specialist finishes which would not normally be associated with a contemporary yacht. These include artisan resin panels and metalized spray and lacquered textured effects.

Have you learned anything?

Having been involved in such a wonderful project has given us a different way of seeing and designing, although of course not all of that can be applied to domestic interiors. It has encouraged us to consider new rhythms of furniture design.

How do you think people will react?

I believe that other people will enjoy slowly observing the yacht and interiors when they first board – in the same way, that people attune themselves to understand abstract art. They will inspect carefully and hopefully understand and warm to their surroundings.

Can you sum up the project in a few words?

It has certainly been, quite literally, a learning curve. Our voyage on land with the team has been educational and we hope the journey continues and that the yacht proves itself to be something really special – ‘The Beast’ of speed and fun.

Update January 28th, 2018: NGONI won two awards at the Boat International Design & Innovation Awards 2018 in Kitzbühel: Best Naval Architecture & Best Exterior Styling Sailing Yachts.

Launch and Construction Impressions

Video by Cloudshots

SHARING IS CARING - THANK YOU!

G 64 // sfg yacht design // fancy by dada, benetti fb270 for chinese market, n2h by rossinavi is out of the shed, ulysses // kleven // 116m, amels 200 with interior design by laura pomponi, sirena 42m superyacht, mulder thirtysix delta one, stella di mare // cbi navi.

About Publisher

Using a minimum of third party cookies for YouTube, Vimeo and Analytics.

Privacy Preference Center

Privacy preferences.

Google Analytics

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

Sailboat Design Evolution

- By Dan Spurr

- Updated: June 10, 2020

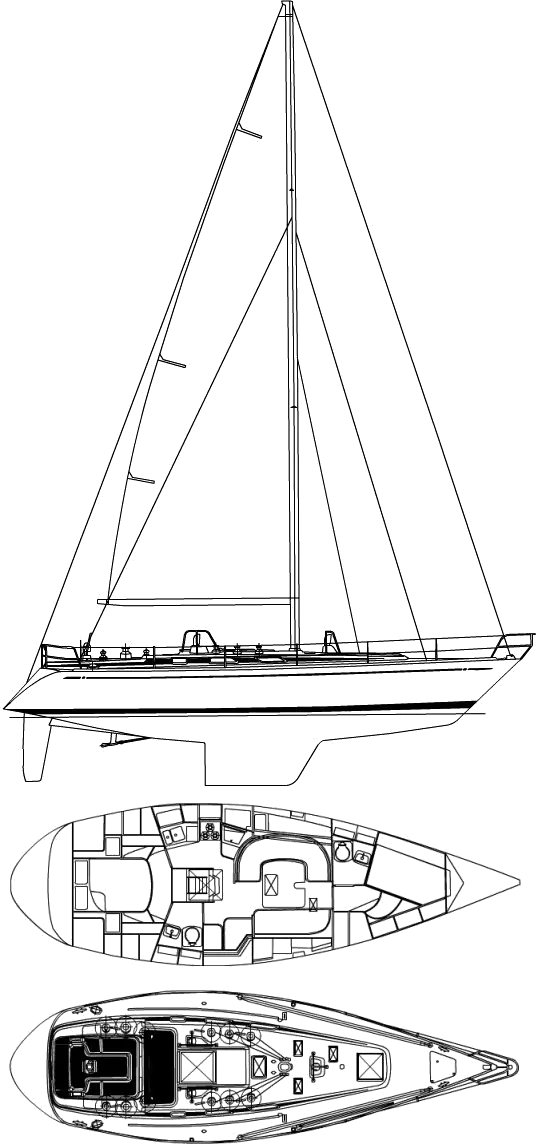

You know the old saying, “The more things change, the more they stay the same”? As a judge for the 2020 Boat of the Year (BOTY) competition at this past fall’s US Sailboat Show in Annapolis, Maryland, I helped inspect and test-sail 22 brand-new current-model sailboats. And I came away thinking, Man, these aren’t the boats I grew up on. In the case of new boats, the saying is wrong: “Nothing stays the same.”

OK, sure, today’s boats still have masts and sails, and the monohulls still have keels. But comparing the Hinckley Bermuda 40, considered by many to be one of the most beautiful and seaworthy boats of the 1960s, ’70s and even ’80s, with, say, the Beneteau First Yacht 53, which debuted at the show, is pretty much apples and oranges.

To get a better sense of what has happened to yacht design, boatbuilding and equipment over the past three, four or even six decades, let’s take a closer look.

Design Dilemmas

At the risk of oversimplification, since the fiberglass era began in the late 1940s and ’50s, the design of midsize and full-size yachts has transitioned from the Cruising Club of America rules, which favored all-around boats (racers had to have comfortable interiors) with moderate beam and long overhangs, to a succession of racing rules such as the IOR, IMS and IRC. All of them dictated proportions, and each required a measurer to determine its rating.

As frustration grew with each (no handicap rule is perfect), alternatives arose, such as the Performance Handicap Racing Fleet, which essentially based one’s handicap on past performance of the same boats in the same fleet. Also, one-design racing became more popular, which spread beyond identical small boats to full-size yachts, popularized in part by builders such as J/Boats and Carroll Marine. The ethos there was: Who cares about intricate rating rules? Let’s just go out and sail fast and have fun!

And that might best sum up the design briefs for the monohulls in this year’s BOTY competition: good all-around performance with comfortable, even luxurious accommodations. Gone are interiors that noted naval architect Robert Perry called “the boy’s cabin in the woods,” deeply influenced by stodgy British designers of the past century and their now-old-fashioned (though sea-friendly, one should note) concepts of a proper yacht, drawn and spec’d by the same guy who designed the hull, deck and rig. Today, dedicated European interior designers are specially commissioned to inject modernity, home fashion colors and textures, amenities, and more light—even dubiously large port lights in the topsides.

Overhangs, bow and stern, have virtually disappeared. Why? It seems largely a matter of style. Plus, the bonus of increased usable space below, not to mention a longer waterline length for a given length overall, which translates to more speed. Former naval architect for C&C Yachts and Hunter Marine, Rob Mazza, recalls that 19th-century pilot cutters and fishing schooners operating in offshore conditions generally had plumb bows, so in a sense, bow forms have come full circle.

Today’s boats are carrying their wide beam farther aft. Gone are the days of the cod’s head and mackerel tail. Wide, flat canoe bodies are decidedly fast off the wind, and might even surf, but they pay a comfort penalty upwind.

These boats have lighter displacement/length (D/L) ratios, which means flatter bottoms and less stowage and space for tanks. The Beneteau 53 has a D/L of 118, compared with the aforementioned Bermuda 40 of 373. Among entries in this year’s BOTY, the heaviest D/L belonged to the Elan Impression 45.1, with a D/L of 195. Recall that when Perry’s extremely popular Valiant 40 was introduced in 1975, the cruising establishment howled that its D/L of 267 was unsuitable for offshore sailing. My, how times have changed!

Perhaps more important, one must ask: “Have the requirements for a good, safe bluewater cruiser actually changed? Or are the majority of today’s production sailboats really best-suited for coastal cruising?”

The ramifications of lighter displacement don’t end there; designers must consider two types of stability: form and ultimate. As weight is taken out of the boat, beam is increased to improve form stability. And with tanks and machinery sometimes raised, ballast might have to be added and/or lowered to improve ultimate stability.

What else to do? Make the boat bigger all around, which also improves stability and stowage. Certainly the average cruising boat today is longer than those of the earlier decades, both wood and fiberglass. And the necessarily shallower bilges mean pumps must be in good shape and of adequate size. That’s not as immediate an issue with a deep or full keel boat with internal ballast and a deep sump; for instance, I couldn’t reach the bottom of the sump in our 1977 Pearson 365.

And how do these wide, shallow, lighter boats handle under sail? Like a witch when cracked off the wind. We saw this trend beginning with shorthanded offshore racers like those of the BOC Challenge round-the-world race in the early 1980s. As CW executive editor Herb McCormick, who has some experience in these boats, says, “They’ll knock your teeth out upwind.” But route planning allows designers to minimize time upwind, and cruisers can too…if you have enough room and distance in front of you. Coastal sailors, on the other hand, will inevitably find even moderate displacement boats more comfortable as they punch into head seas trying to make port.

A wide beam carried aft permits a number of useful advantages: the possibility of a dinghy garage under the cockpit on larger boats; easy access to a swim platform and a launched dinghy; and twin helms, which are almost a necessity for good sightlines port and starboard. Of course, two of anything always costs twice as much as one.

Some multihulls now have reverse bows. This retro styling now looks space-age. Very cool. But not everyone is sold on them. Canadian designer Laurie McGowan wrote in a Professional BoatBuilder opinion piece, “I saw through the fog of faddishness and realized that reverse bows are designed to fail—that is, to cause vessels to plunge when lift is required.” Mazza concurs: “Modern multihulls often have reverse stems with negative reserve buoyancy, and those are boats that really can’t afford to bury their bows.”

McGowan also cites another designer critiquing reverse bows for being noticeably wet and requiring alternative ground-tackle arrangements. The latter also is problematic on plumb bows, strongly suggesting a platform or sprit to keep the anchor away from the stem.

Rigging Redux

If there was a boat in Annapolis with double lower shrouds, single uppers, and spreaders perpendicular to the boat’s centerline, I must have missed it. I believe every boat we sailed had swept-back spreaders and single lowers. An early criticism of extreme swept-back spreaders, as seen on some B&R rigs installed on Hunter sailboats, was that they prevented fully winging out the mainsail. The counter argument was that so many average sailors never go dead downwind in any case, and broad reaching might get them to their destinations faster anyway—and with their lunch sandwiches still in their stomachs.

That issue aside, the current rigging configuration may allow for better mainsail shape. But as Mazza points out, it’s not necessarily simple: “By sweeping the spreaders, the ‘transverse’ rigging starts to add fore-and-aft support to the midsection of the mast as well, reducing the need for the forward lowers. However, spreader sweep really does complicate rig tuning, especially if you are using the fixed backstay to induce headstay tension. Swept spreaders do make it easier to sheet non-overlapping headsails, and do better support the top of the forestay on fractional rigs.”

Certainly, the days of 150 percent genoas are over, replaced by 100 percent jibs that fit perfectly in the foretriangle, often as a self-tacker.

Another notable piece of rigging the judges found common was some form of lazy jacks or mainsail containment, from traditional, multiple lines secured at the mast and boom; to the Dutchman system with monofilament run through cringles sewn into the sail like a window blind; to sailmaker solutions like the Doyle StackPak. This is good news for all sailors, especially those who sail shorthanded on larger boats.

Construction Codas

Improvements in tooling—that is, the making of molds—are easily evident in today’s boats, particularly with deck details, and in fairness. That’s because many of today’s tools are designed with computer software that is extraordinarily accurate, and that accuracy is transferred flawlessly to big five-axis routers that sculpt from giant blocks of foam the desired shape to within thousandths of an inch. Gone are the days of lofting lines on a plywood floor, taken from a table of offsets, and then building a male plug with wood planks and frames. I once owned a 1960s-era sailboat, built by a reputable company, where the centerline of the cockpit was 7 degrees off the centerline of the deck—and they were one piece!

Additive processes, such as 3D printing, are quickly complementing subtractive processes like the milling described above. Already, a company in California has made a multipart mold for a 34-foot sailboat. Advantages include less waste materials.

Job training also has had an impact on the quality of fiberglass boats. There are now numerous schools across the country offering basic-skills training in composites that include spraying molds with gelcoat, lamination, and an introduction to vacuum bagging and infusion.

The patent on SCRIMP—perhaps the first widely employed infusion process—has long ago expired, but many builders have adopted it or a similar process whereby layers of fiberglass are placed in the mold dry along with a network of tubes that will carry resin under vacuum pressure to each area of the hull. After careful placement, the entire mold is covered with a bag, a vacuum is drawn by a pump, and lines to the pot of resin are opened. If done correctly, the result is a more uniform fiberglass part with a more controlled glass-to-resin ratio than is achievable with hand lay-up. And as a huge bonus, there are no volatile organic compounds released into the workplace, and no need for expensive exhaust fans and ductwork. OSHA likes that, and so do the workers.

However, sloppy processes and glasswork can still be found on some new boats. Surveyor Jonathan Klopman—who is based in Marblehead, Massachusetts, but has inspected dozens, if not hundreds, of boats damaged by hurricanes in the Caribbean—tells me that he is appalled by some of the shoddy work he sees, such as balsa cores not vacuum-bagged to the fiberglass skins, resulting in delamination. But overall, I believe workmanship has improved, which is evident when you look behind backrests, inside lockers and into bilges, where the tidiness of glasswork (or lack thereof) is often exposed. Mechanical and electrical systems also have improved, in part due to the promulgation of standards by the American Boat & Yacht Council, and informal enforcement by insurance companies and surveyors.

We all know stainless steel isn’t entirely stainless, and that penetrations in the deck are potentially troublesome; allowing moisture to enter a core material, such as end-grain balsa, can have serious consequences. The core and fiberglass skins must be properly bonded and the kerfs not filled with resin. Beginning in the mid-1990s, some builders such as TPI, which built the early Lagoon cruising catamarans, began using structural adhesives, like Plexus, to bond the hull/deck joint rather than using dozens of metal fasteners. These methacrylate resins are now commonly used for this application and others. Klopman says it basically should be considered a permanent bond, that the two parts, in effect, become one. If you think a through-bolted hull/deck joint makes more sense because one could theoretically separate them for repairs, consider how likely that would ever be: not highly.

Fit-and-Finish

Wide transoms spawned an unexpected bonus; besides the possibility of a dinghy “garage” under the cockpit on larger boats, swim platforms are also possible. In more than one BOTY yacht, the aft end of the cockpit rotated down hydraulically to form the swim platform—pretty slick.

Teak decks are still around, despite their spurning for many years by owners who didn’t want the upkeep. In the 1960s and ’70s, they were considered a sign of a classy boat but fell from favor for a variety of reasons: maintenance, weight and threat of damaging the deck core (the bung sealant wears out and water travels down the fastener through the top fiberglass skin into the core). Specialty companies that supply builders, like Teakdecking Systems in Florida, use epoxy resin to bond their product to decks rather than metal fasteners. And the BOTY judges saw several synthetic faux-teak products that are difficult to distinguish from real teak—the Esthec installed on the Bavaria C50 being one example.

LPG tanks no longer have to be strapped to a stanchion or mounted in a deck box because decks now often incorporate molded lockers specifically designed for one or two tanks of a given size. To meet ABYC standards, they drain overboard. In tandem with these lockers, some boats also have placements or mounts for barbecues that are located out of the wind, obviating the common and exposed stern-rail mount.

Low-voltage LED lights are replacing incandescent bulbs in nearly all applications; improvements in technology have increased brightness (lumens), so some even meet requirements for the range of navigation lights. Advances in battery technology translate to longer life, and depending on type, faster charging. And networked digital switching systems for DC-power distribution also are becoming more common.

Last, I was surprised at how many expensive yachts exhibited at Annapolis had nearly the least-expensive toilets one can buy. Considering the grief caused by small joker valves and poorly sealed hand pumps, one would think builders might install systems that incorporate higher-quality parts or vacuum flushing, and eliminate the minimal hosing that famously permeate odors.

Dan Spurr is an author, editor and cruising sailor who has served on the staffs of Cruising World, Practical Sailor and Professional Boatbuilder. His many books include Heart of Glass , a history of fiberglass boatbuilding and boatbuilders .

Other Design Observations

Here are a few other (surprising) items gleaned from several days of walking the docks and sailing the latest models:

- Multihulls have gained acceptance, though many production models are aimed more at the charter trade than private ownership for solitary cruising. You’d have to have been into boats back in the ’60s and ’70s to remember how skeptical and alarmist the sailing establishment was of two- and three-hull boats: “They’ll capsize and then you’ll drown.” That myth has been roundly debunked. Back then, the only fiberglass-production multihulls were from Europe, many from Prout, which exported a few to the US. There are still plenty of European builders, particularly from France, but South Africa is now a major player in the catamaran market.

- The French builders now own the world market, which of course includes the US. Other than Catalina, few US builders are making a similar impact. In terms of volume, Groupe Beneteau is the largest builder in the world, and they’ve expanded way beyond sailboats into powerboats, runabouts and trawlers.

- Prices seem to have outpaced inflation, perhaps because, like with automobiles, where everyone wants air conditioning, electric windows and automatic transmissions, today’s boats incorporate as standard equipment items that used to be optional. Think hot- and cold-pressure water, pedestal-wheel steering, and full suites of sailing instruments and autopilots.

- More: design , print may 2020 , Sailboats

- More Sailboats

A Gem in New England

Thinking of a Shift to Power?

TradeWinds Debuts 59-foot TWe6 Smart Electric Yacht

Sailboat Preview: Dufour 44

How To Prioritize Your Sailboat’s Spring Checklist

Good Bread for Good Health

Center of Effort

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

THE WORLD’S LARGEST SLOOP

AN UNPRECEDENTED OPPORTUNITY FOR AN INSPIRED OWNER

The APEX 850 mega sloop is one of the most exciting concepts the yachting world has ever seen. Dramatic in scale yet elegant in appearance, the 85 m / 279 ft APEX features a mind-blowing 107 m / 351 ft rig, qualifying as both the world’s largest sloop and the world’s largest aluminium sailing yacht. She will effortlessly join the top ten largest sailing boats.

Inspirational design from celebrated naval architect Malcom McKeon and innovative engineering from Royal Huisman have resulted in a fully-resolved concept for a mega yacht that is bold and ambitious enough to comprehensively redefine on-board lifestyle and sailing experiences.

Just add the refinements that express the vision and creativity of an inspired owner and she will be ready to commence construction. Once on the water, the world will look on in awe.

“Two of the world’s ten largest sailing yachts, ATHENA and SEA EAGLE II, are Royal Huisman builds and APEX 850 would make a fitting third, easily becoming the largest member of this elite circle.”

AN ICONIC COLLABORATION

The innovators behind APEX 850 – Malcolm McKeon Yacht Design and Royal Huisman – come with a pedigree that hardly needs introduction to followers of the world’s leading super-sailing yachts. Enjoy watching the video with the designer’s and builder’s comments.

Technically, APEX is a fully resolved concept as you can see via the links below . Yet there remains extensive scope for an Owner to incorporate their own ideas and apply their creativity to realise a personal vision for APEX 850. The Malcolm McKeon / Royal Huisman team are ready to discuss your ideas and help translate them into reality. As we like to say at Royal Huisman: “If you can dream it, we can build it”.

Just ask us about the possibilities.

THE ULTIMATE VIRTUAL EXPERIENCE

There is an amazing, stereoscopic Oculus 3D virtual tour exclusively available to prospective Owners. The depth of field and quality of presentation offered by this technology provide the viewer with the most extraordinary, fully immersive, experience of being aboard the world’s largest sloop.

A preview can be found via the online 360 VR tour: click here.

MAKING AN IMPRESSION

OWNERS’ APARTMENT

CLOSE CONNECTION WITH THE SEA

THE HEIGHT OF ELEGANCE

PERFORMANCE, COMFORT AND SECURITY

RIG AND SAILING SYSTEMS BY RONDAL

AT SEA, UNDER SAIL

PROPULSION AND ENERGY MANAGEMENT

360 VR TOUR

MAIN SPECIFICATIONS

YOUR INDIVIDUAL DREAM

One of the nice things about fashioning successful yachts from across the design spectrum is the leeway it gives to blend ideas. This sleek 133-foot sloop is a superb example as she has a hull shape somewhere in-between Aphrodite I and Bharlin Blue, yet the design is not as plumb-bowed as Aphrodite II and has a narrower stern than Temptation. The original client intended to explore remote areas, hence the inclusion of a distinctive pilot house concept with wraparound windows, within which is incorporated a navigation station and breakfast area. The interior layout also includes an upper saloon with formal dining room, a lower multimedia lounge and three guest suites. Impressive as these areas are, the pièce de résistance below decks is a giant owner's stateroom with walk-in wardrobes. Although changed circumstances forced a rethink for the client, this design simply must take physical shape in the near future. Contact [email protected] for more details.

LOA 40.5 m LWL 35.4 m Beam 8.7 m Draft 1.8 - 4.0 m Sail Area 715 m2

Big Class Yachts

Cruising yachts, j-class yachts, square rigged ships, miscellaneous.

- Motor Yachts

51 M Project Rain...

51 m project rainbow ....

65 M Aquarius II

69 m Project ZERO

81 M Sea Eagle

Aurelius (ex Anna...

Aurelius (ex annagine....

Aurelius (ex Annagine)

Bestevaer 2

Bestevaer 3

Bestewind 50

Black Pearl

Borkumriff IV

Cisne Branco

Dream Symphony

Geluksvogel

JH2 Rainbow

JK3 Shamrock V

JK4 Endeavour

JK6 Hanuman

JK7 Velsheda

Maltese Falcon

Mikhail S Voronts...

Mikhail s vorontsov.

MY Bestevaer 53

Perseverance

Perseverance 1

Rainbow Warrior I...

Rainbow warrior iii.

Rapsody R110

Sea Bridge One

Shabab Oman II

Stad Amsterdam

WASP (Ecoliner)

Windjammer Project

Windrose of Amste...

Windrose of amsterdam.

Full list of Designs

Dykstra Naval Architects' designed yachts, vessels and concept designs throughout the years:

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

What You Can Learn on a Quick Test Sail

Cabo Rico’s Classic Cutter

Bob Perrys Salty Tayana 37-Footer Boat Review

Tartan 30: An Affordable Classic

Preparing Yourself for Solo Sailing

Your New Feature-Packed VHF Radio

Preparing A Boat to Sail Solo

Solar Panels: Go Rigid If You have the Space…

When Should We Retire Dyneema Stays and Running Rigging?

Rethinking MOB Prevention

Top-notch Wind Indicators

The Everlasting Multihull Trampoline

Taking Care of Your 12-Volt Lead-Acid Battery Bank

Hassle-free Pumpouts

What Your Boat and the Baltimore Super Container Ship May Have…

Check Your Shorepower System for Hidden Dangers

Waste Not is the Rule. But How Do We Get There?

How to Handle the Head

The Day Sailor’s First-Aid Kit

Choosing and Securing Seat Cushions

How to Select Crew for a Passage or Delivery

Re-sealing the Seams on Waterproof Fabrics

Waxing and Polishing Your Boat

Reducing Engine Room Noise

Tricks and Tips to Forming Do-it-yourself Rigging Terminals

Marine Toilet Maintenance Tips

Learning to Live with Plastic Boat Bits

- Sailboat Reviews

Practical Sailor Takes a Look at Trends in Modern Boat Design

Is the quest for speed and interior comfort trumping smart design in todays sailboats.